On "Evolution"

Buffalo Bill and the confiscation of culture

by Benjamin Branham

Pawn shops tend to represent sites of unorganized accumulation, places that gather anything and everything with the prospect of profiting from the vulnerability of others. By enticing patrons with quick cash--an instantaneous materialization of value--the pawn shop successfully confiscates living objects only to deprive them of meaning by re-offering them for sale. Sherman Alexie adapts this story poignantly in "Evolution."

Alexie centers the enterprise of objectification in the figure of Buffalo Bill. Also known as William F. Cody (1846-1917), Buffalo Bill, no longer just an historical figure but rather an icon now synonymous with the American West, did at least his share in exploiting Native Americans. An honorary website credits him with helping "his West to make the transition from a wild past to a progressive future." The establishment of a binary between "wild" and "progressive" subjugates Indians by placing them in the role of savages, a representation that American history has repeatedly thrust upon them. Despite supposedly championing the rights of Indians, Buffalo Bill certainly contributed to their cultural confinement in his "Wild West" shows, performances that "contained elements of the circus, the drama of the times, and the rodeo," offering a "unique form of theatrical entertainment. The Wild West Show had as its theoretical aim the presentation of a pageant of the settling and the taming of the West" (Kramer 87). Beyond mere amusement, the shows also served as advertising campaigns to lure settlers to the West to help further tame the "uncivilized" region:

The Wild West show was inaugurated in Omaha in 1883 with real cowboys and real Indians portraying the "real West." The show spent ten of its thirty years in Europe. In 1887 Buffalo Bill was a feature attraction at Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee. At the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893, only Egypt's gyrations rivaled the Wild West as the talk of Chicago. By the turn of the century, Buffalo Bill was probably the most famous and most recognizable man in the world. (American West)

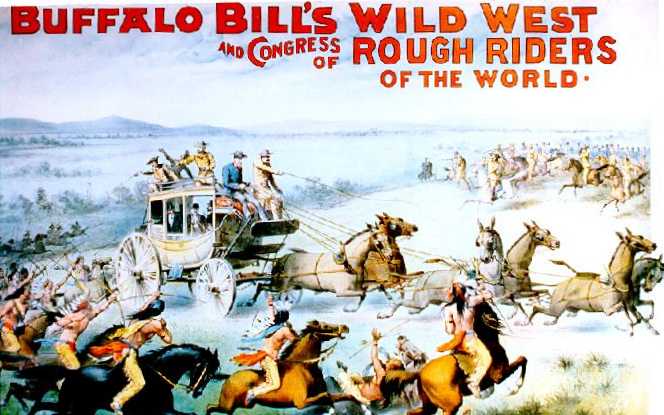

Given the legendary status history has accorded him, Buffalo Bill may be compared to other colonizing heroes in Western culture, especially those who circulated a dominant ideology as their role in enhancing domination. His ability to disseminate representations stems not only from his ubiquitous stage presence but also from the extensive publicity that presented his image. "Certainly no individual, before the days of movies and radio, ever had such effective personal exploitation. For nearly half a century he was continuously held before the public, in the pages of nickel and dime novels, on the boards in blood and thunder melodrama and in that astounding Wild West Show which toured from the tank towns to the very thrones of Europe" (Walsh 18). The title of a 1928 book, The Making of Buffalo Bill: A Study in Heroics, suggests that the phenomenon of Buffalo Bill was as much created by an eager audience as it was by Bill Cody. Its collective gaze, like the gaze performed by museum-goers, constructed an impervious ideal: "When they gazed upon the man himself they saw that he looked the part of hero" (Walsh 17). Empowered with the iconic eminence of a hero, Buffalo Bill possesses the capacity and authority to reproduce and distribute cultural myths. His conception of the "real West" extends from his imaginary relation to American ideals that have themselves been formed by such hegemonic historical representations as Manifest Destiny. The posters advertising Buffalo Bill (see below) contribute to the representational subjugation of Indians, portraying them as features of a crude land that the military must rehabilitate and civilize.

The illustration depicts Buffalo Bill and his entourage riding in a "civilized" wagon through a tumultuous landscape. As the central focus, they marginalize the Indians on the borders of the painting, indeed cutting some of them off as they forcibly split the factions on both sides of their procession. The white riders stand taller than the encroaching Indians, a force that the advertisement construes as a threat to American progress. Such a hazard, the painting declares, must be vanquished by the collective gaze of American discourse, a gaze that restricts Native American culture to a territory of enclosure.

In "Evolution," Alexie addresses the compartmentalization and commodification of culture by supplanting Buffalo Bill's stage antics with a business venture:

Buffalo Bill opens up a pawn shop on the reservation

Right across the border from the liquor store

And he stays open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week

And the Indians come running in with jewelry

Television sets, a VCR, a full-length beaded buckskin outfit

it took Inez Muse 12 years to finish. (1-6)

Alexie re-appropriates history to fit the mold of a "24 hours a day, 7 days a week" contemporaneity. Placing it across the "border," rather than across the street from the liquor store, Alexie reminds us of the laws forbidding the sale of alcohol on many Indian reservations and the physical and cultural boundaries that continue to encircle them. The liquor store further calls attention to the use of alcohol as a device of suppression. Numerous historical accounts tell of white residents getting Indians drunk as a negotiation strategy to convince them to sign treaties that would yield land (Barr 7). The high rate of alcoholism that persists among Native Americans occupies a prominent position throughout all of Alexie's work. In "Evolution," Alexie intimates that the money the Indians obtain from pawning themselves evaporates when they cross the street to purchase liquor. This vicious cycle in which everyone stands to profit from Indians except Indians themselves sustains itself because "Buffalo Bill / takes everything the Indians have to offer, keeps it / all catalogued and filed in a storage room" (6-8). Buffalo Bill scavenges all he can, classifying it with the commodifying gaze of a museum curator. The cycle culminates in Buffalo Bill's move from collecting to exhibition:

and when the last Indian has pawned everything

but his heart, Buffalo Bill takes that for twenty bucks

closes up the pawn shop, paints a new sign over the old

calls his venture THE MUSEUM OF NATIVE AMERICAN CULTURES

charges the Indians five bucks a head to enter. (11-15)

By seizing the "heart" of the last Indian and subsequently closing the doors of the pawn shop, Buffalo Bill seals out the possibility of repossession. This act deprives the culture of its lifeblood. The new museum freezes "NATIVE AMERICAN CULTURES" in place, on display, behind glass cases. The painted over sign recalls the years of government manipulation of Indians in which new treaties invalidated old ones that the U.S. no longer wished to honor. The glossing over of old wounds and forms of cultural exploitation--feeding a people someone else's idea of what they should be--cap this poem with the absurd reality of a perverse history.

Jane Tompkins comments on the manifestation of another absurd reality in her visit to a museum in Cody, Wyoming that enshrines Buffalo Bill himself. The existence of this memorial ironically shifts the position of the celebrated pioneer from curator to spectacle. However, unlike the cultural deprivation enacted by the museum of Alexie's poem, the Buffalo Bill Museum petrifies the superhero status of its namesake. Both instances cast a type of paralysis--The Museum of Native American Cultures frames its objects as an exhibition of a primitive culture, a display of dry bones; The Buffalo Bill Museum, as Tompkins tells us, galvanizes the golden image of an American icon:

The Buffalo Bill Museum envelops you in an array of textures, colors, shapes, sizes, forms. The fuzzy brown bulk of a buffalo's hump, the sparkling diamonds in a stickpin, the brilliant colors of the posters--there's something about the cacophonous mixture that makes you want to walk in and be surrounded by it, as if you were going into a child's adventure story. It all appeals to the desire to be transported, to pretend for a little while that we're cowboys or cowgirls; it's a museum where fantasy can take over. In this respect, it is true to the character of Buffalo Bill's life. (Tompkins 530)

The fantasy of Buffalo Bill's life is the fantasy projected onto it by the gaze of a

hungry audience. For years Americans and viewers around the world stood captivated by the

Wild West Show, feeding off its depictions of conquest, control, and violence. Tompkins

gives us the severe yet appropriate metaphor that "museums are a form of cannibalism

made safe for

polite society," serving as venues that "cater to the urge to absorb the life of

another into one's own life" (533). This remark accords with an attitude Alexie

voices throughout his work. The dominant culture devours its subordinates to sustain its

stance as an enforcer. "The objects in museums preserve for us a source of life from

which we need to nourish ourselves when the resources that would normally supply us have

run dry" (Tompkins 533). The act of sapping resources from another culture again

points to the narrative of "Evolution," a title that drips with the irony of the

concept of civilization. A civilized culture, Alexie implies, must "evolve"

enough to perfect the practice of stealing and plundering other cultures for the purpose

of presenting them as uncivilized behind the glass case of the museum. We too, Tompkins

reminds us, are onlookers. "We

stand beside the bones and skins and hooves of beings that were once alive, or stare

fixedly at their painted images. Indeed our visit is only a safer form of the same

enterprise" (533) rehearsed by Buffalo Bill's Wild West show--cultural

objectification and destruction.

Bibliography of Works Cited:

"Buffalo Bill," The American West. 10 December 2000. <http://www.americanwest.com/pages/buffbill.htm>.

Kramer, Mary D., "The American Wild West Show and 'Buffalo Bill' Cody," Costerus:

Essays in English and American Literature, 4 (1972): 87-97.

Tompkins, Jane, "At the Buffalo Bill Museum--June 1988," South Atlantic

Quarterly 89.3 (Summer 1990): 525-545.

Walsh, Richard J., The Making of Buffalo Bill, Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill

Company, 1928.

Copyright © 2001 by Benjamin Branham

Return to Sherman Alexie