"A Political Poet"--An Essay on John Beecher by Frank Adams

Frank Adams

Reprinted from Southern Exposure (1981)

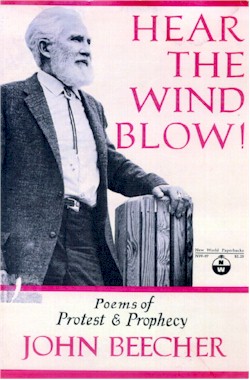

His name was suggestive: even so a superficial reading of his poetry proves conclusive: John Beecher was a radical poet, perhaps America's most persistent for 50 years, the heir of an Abolitionist tradition and proponent of the dispossessed seizing power. His most enduring lyrics are about the downtrodden's fight for economic justice, human dignity and political freedom. He heard the music in their voices with uncanny accuracy.

His own life,

too, was an obstinate confrontation against being reined in or, what he feared as

passionately in his later years, unwarranted obscurity. For years, save what publicity he

could generate himself, John Beecher failed to gain much notice. His subject matter was

one reason; his fiery character another. A friend, maybe his only ardent personal admirer

in Montgomery, Alabama, once described Beecher as a perpetually sore toe in a too tight

shoe.

His own life,

too, was an obstinate confrontation against being reined in or, what he feared as

passionately in his later years, unwarranted obscurity. For years, save what publicity he

could generate himself, John Beecher failed to gain much notice. His subject matter was

one reason; his fiery character another. A friend, maybe his only ardent personal admirer

in Montgomery, Alabama, once described Beecher as a perpetually sore toe in a too tight

shoe.

Beecher was well born. His father owned a large share of Tennessee Coal and Iron, a prosperous firm in Grundy Count Tennessee, which was bought up by U.S. Steel and the J.P. Morgan banking interests. John was born in New York City on January 22, 1904. As an adult, he seldom let the opportunity pass to remind listeners, in his usually small audiences, that among his father's family was a galaxy of the celebrated -- New England Calvinist Lyman Beecher, Henry Ward Beecher, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Catherine Beecher, Isabella Beecher Hooker, General James Beecher and Dr. Edward Beecher, the family's pioneer abolitionist. The poet wore this heritage proudly.

While John was still a boy, his father was sent by U.S. Steel to Birmingham, where John was reared a Catholic amidst the revival of the Ku Klux Klan. During the summers, he attended military camps; he graduated from high school at age 14, still too young for the military career he was planning. So his father got him a job in the steel mill's laboratory, mostly running errands. Some months later, in 1919, he enrolled at Virginia Military Institute, the youngest cadet in that gray collegiate corps. Perhaps it was the Calvinist in him, but during his sophomore year Beecher's dreams of a military career were dashed. He refused to "rat" on a roommate and was "shipped."

For the next six years, his life was a mixture of academic vagabondage punctuated with sweat-streaked stints at the faces of open hearth furnaces in the Birmingham mills. Those were the days of the 12-hour shift, six days and seven nights turn and turn about, even for the boss' son. Here he wrote his first poetry; here was the source of his idealism, and here were the voices he would chronicle with force, simplicity and clarity, much in the tradition of Whitman. His first poems, "Report to the Stockholders," were as sardonic as their title and presaged much of his later work. One sample:

he didn't understand why he was laid off

when he'd been doing his work

on the pouring tables OK

and when men with less age than he had

weren't laid off

and he wanted to know why

but the superintendent told him to get the hell out

so he swung on the superintendent’s jaw

and the cops came and took him away

Knowing he wanted to do more with his life than pitch coal into a furnace, John enrolled at Cornell to study engineering. His poems caught the attention of William Strunk, Jr., an English instructor who was elaborating a few simple rules of writing and later would be lionized. Strunk introduced Beecher to Carl Sandburg and other working poets. Engineering paled. He quit Cornell to return to the steel mills and writing. Eventually, he finished college at the University of Alabama in 1925, and that summer went to Middlebury College's Bread Loaf School of English, where he studied with Robert Frost. Again he returned to the mills, but this would be the last time for he was badly injured. He wrote eloquently and often about occupational hazards in those early poems -- with especial poignancy about surviving cripples:

he shouldn't have loaded and wheeled

a thousand pounds of manganese

before the cut in his belly was healed

but he had to pay his hospital bill

and he had to eat

but he found out

he was wrong

Beecher never wrote private poems, only for his own ear, or to provide engaging complexities for the learned or the critic. Like Isaiah, or Bunyan, and even Sandburg for a time, his poems were for average people. Beecher seemed to know instinctively that poetry was not just for the critics, but that people used it in one way or another every day not to flatter but to survive, to express the uncommon or mysterious in their own, often tragic, lives. The poet's task was to listen, to record, then to chant his poetry. Much of what he heard, even as a young man, was the voice of rebellion, the experiences of poor people, untarnished by propaganda or ideological platitude.

In the mid-1920s, Beecher left the South for Harvard to study literature for a year. He then won an appointment to Dartmouth as an English instructor. A year of that and he left for Europe to study at the Sorbonne. When the stock market crashed in 1929, Beecher was back in Birmingham in the mills, working as an open hearth metallurgist. More defiant poems rolled from his experiences:

old man John the melter

wouldn't tap steel till it was right

and he let the superintendents rave

he didn't give a damn about tonnage

but he did give a damn about steel

. . . and the steel got sorrier and sorrier

and the rails got to breaking under

trains and the railroads quit buying,

and the mill shut down

and then the superintendents asked

old man John

to come and tell them what was wrong

with the steel and he told them

too many superintendents

Restlessness struck again in 1929. it had a perpetual place in his life. He left the mills to join Dr. Alexander Meiklejohn's famed, but short-lived, Experimental College at the University of Wisconsin in Madison as an English instructor. He taught there four years, earned a master's degree and sharpened his inherent civil libertarian's instincts at the side of Meiklejohn, already a noted dissenter.

Beecher landed in Chapel Rill next, helping Howard W. Odum at the University of North Carolina compile his influential Southern Regions of the United States. In 1934, Beecher was asked to study sharecroppers' organizations. He published his findings in Social Forces, a respected journal of sociology. But what he'd seen and heard of Alabama sharecroppers during his research propelled him into a more direct engagement with the defiances he witnessed. He began a long narrative poem about two ignored American patriots, Cliff James and Ned Cobb, who fought and suffered trying to build a tenant farmers' union. Their heroics brought out the best in Beecher. The resulting epic, "In Egypt Land," is an evocative tribute to two men, who happened to be black, who refused to behave with the submissiveness demanded of them as black tenant farmers. His poem, like their defiance, was out of kilter with the times. Polite circles, even liberal ones, did not want to hear of blacks taking command of their own destinies, of their using guns, of their asserting a sense of self not beholden to whites.

"You"

Cliff James said

"nor the High Sheriff"

nor all his deputies

is gonna git them mules.

The head deputy put the writ of

attachment back in his inside

then his hand went to the butt of his

pistol

but he didn't pull it.

"I'm going to get the High Sheriff

and help"

he said

"and come back and kill you all

in a pile."

Cliff James and Ned Cobb watched the

deputy whirl the car around

and speed down the rough mud road.

He took the turn skidding

and was gone.

"He’ll be back in an hour, " Cliff

James said

If’n he don’t wreck hisself."

"Where you fixin' to go?" Ned Cobb

asked him.

'I’s fixin’ to stay right where I is."

I’ll go git the others then."

"No need of ever-body gittin’ kilt"

than perishin' slow like we been a'doin"'

and Ned

Cobb was gone.

For years the poem's only notice were the rejection slips sent to Beecher. He fumed at being spurned, wondering aloud about "gutless publishers" in sometimes petulant terms. Other poems he was writing at the time weren't being published either. "In Egypt Land" and other poems of the South's people before the second world war were eventually printed by Beecher himself in a volume; titled To Live and Die in Dixie. (Not until 1974 did a "'regular" publication Southern Exposure print "In Egypt Land," and the magazine's editors endeared themselves to Beecher forever.) On the other hand, Beecher's irascibility came out most clearly after the publication of All God's Dangers, an oral history of the life of Ned Cobb. The author's note in the first edition of the book contained a reference to Beecher's pioneering in the struggle 40 years before, but mentioned neither "In Egypt Land" nor the Social Forces article. Beecher, who had in fact introduced Ted Rosengarten to Cobb's story, was furious. The paperback reprinting of All God's Dangers after the book received national acclaim fully acknowledged the author’s debt to Beecher and to "In Egypt Land."

By the completion of "In Egypt Land" in 1940, Beecher had left Chapel Hill to run a succession of New Deal agencies. He administered relief in North Carolina. He supervised a study of cotton tenancy in the Mississippi Delta, then surveyed farm labor conditions in the Southeast. He helped resettle farm families, and managed a resettlement project himself for three years. He opened resettlement camps in the Florida Everglades before abruptly quitting government employ to write editorials for a Birmingham newspaper, and then report news for the New York Post.

In 1943, he joined the Merchant Marine and was assigned to a liberty ship, the Booker T. Washington, one of the few commanded by a black sea captain. In March, 1945, a book about his two years in the North Atlantic and Mediterranean war zones, All Brave Sailors, was published to modest acclaim.

Teaching again lured him at the end of the war, and in 1948 he was appointed assistant professor of sociology at San Francisco State College. At 44, life was good to him: he had a wife, son and daughter; his courses were thriving; the college was growing to university status; San Francisco was grand. In the fall of 1950, just as he was up for tenure, he and other professors were asked to sign a loyalty oath brought on by the anti-left hysteria of McCarthyism. Beecher balked. The oath, he said, was repressive and unconstitutional. He offered to teach without pay until the matter could be settled. Instead, he was fired by the college for "gross unprofessional conduct." There was no appeals hearing. His poem, "Reflections of a Man Who Once Stood Up For Freedom," recounts the events which followed:

And so I got the old heave-ho

from my profession as perhaps

I should have known and after that

I found myself an outcast. Friends

quite naturally avoided me

lest my unclean touch defile them

and when I tried to find a job

all doors were closed against me.

"Why,

it would be easier to place

a convict on parole than you!"

they told me at the office where

I went to seek employment. Then

my son quit college and my daughter

also. She'd wanted to be a teacher

like me. She's now a secretary

while my son, embittered, drifts

from job to job. Their mother failed

to appreciate my heroism.

Quixotic was the kindest term

she found for my behavior. First

we separated. After that

divorce was natural. We'd been

so close for more than twenty years!

Gradually, Beecher regrouped. He bought a small ranch near Sebastopol in Sonoma County and began raising chickens, sheep and fruit. He began writing poetry again, and remarried; his second wife, Barbara, created memorable woodcuts to illustrate her husband's poems. Together, they started Morning Star Press to publish blacklisted or ignored works, including Beecher's. All the while, he brooded over what his principled refusal had cost.

I'll hardly live to see the day

when I’ll be justified at last

if ever that day comes.

He was more fortunate than some. His name was stricken from the banned list in nine years, and soon he was back teaching, this time at Arizona State University, the first of a nearly endless string of places where he'd visit, lecture or reside as "poet in residence." Seventeen years after he'd been dismissed, the U.S. Supreme Court found loyalty oaths unconstitutional. He got hints that his old job could be his if he wanted. Beecher, however, wanted more than a job. He wanted justice and retribution.

By this time, with his flowing white beard and shock of silver white hair, he looked like an Old Testament prophet. He sounded like one, too. Patiently, but never once letting up the pressure, he argued his reinstatement with pay at San Francisco State. Finally, in 1977, the California legislature, perhaps not wishing to have his anger on their consciences, passed a special resolution reinstating him as a full-time professor at San Francisco State University. Beecher was living in Burnsville, North Carolina, when the news arrived. He was 73. Joyously, he left North Carolina to take up a joint appointment in four departments--creative writing, English, humanities and sociology. In 1979, he was awarded $25,000 compensation for financial losses he'd suffered.

Unhappily, his last days were not spent teaching or cherishing honors belatedly given, although some did come his way. Shortly before he rejoined the faculty at San Francisco, Macmillan brought out a collection of his poems written during a 50-year span. Recognition was his at last. There were promotion tours; Birmingham set aside a special day in his honor soon after publication; reviews were full of praise. But the book's sales never took off. Five years later, after the dust settled, Beecher wrote a bitter attack on the editor of the publishing house (See "On Suppression"). Macmillan had failed to distribute the books to reviewers, he said, or to advertise the book in any customary way, and it printed fewer than 5,000 copies -- despite rave reviews in Time and the New York Review of Books.

A final irony in this poet's life occurred just before his death in San Francisco on May 11, 1980. Beecher had spent several years researching the populist movement in the upper Midwest, particularly those rebellious men and women who developed the Grange and People's Party in the late-1800s. His book on the subject, Tomorrow Is a Day, was finally published by the Independent Publishing Fund of the Americas, a house Beecher himself had helped start in 1976 to support the works of "well-known but underpublished writers."

Beecher's poetry represents a tradition at odds with the prevailing styles in the United States between the great wars. He heard the musical sounds in human struggle and protest. Imagery never replaced logic or the uniqueness of the individual's experience. His social criticism never dwelled upon personal malaise, emotional despair, dissatisfaction with the superficial ugliness or the standardization of industrial America. Instead, his poetry and his criticism spoke with a deeper sense of life's driving urge for freedom and dignity. His philosophy molded his style, and dictated the forms, but that philosophy grew from the object of his lyrics. Form and matter coincided. He was indeed a political poet.

Copyright © 1981 by Frank Adams

Return to John Beecher