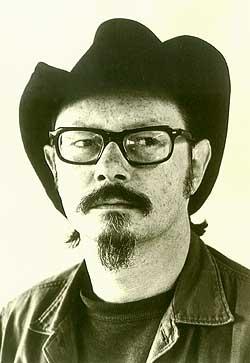

About Paul Blackburn

Robert Creeley

Preface to Against the Silences, by Paul Blackburn

I'd like to speak personally of this extraordinary poet, and take

that license insofar as these poems are personal, often bitterly so. I wonder if any of us

have escaped the painful, self-pitying and meager defenses of person so many of them

invoke. What we had hoped might be, even in inept manner worked to accomplish, has come to

nothing - and whose fault is that, we ask. Certainly not mine? Having known both of these

dear people, and myself, I have to feel that there will never be a human answer, never one

human enough.

I'd like to speak personally of this extraordinary poet, and take

that license insofar as these poems are personal, often bitterly so. I wonder if any of us

have escaped the painful, self-pitying and meager defenses of person so many of them

invoke. What we had hoped might be, even in inept manner worked to accomplish, has come to

nothing - and whose fault is that, we ask. Certainly not mine? Having known both of these

dear people, and myself, I have to feel that there will never be a human answer, never one

human enough.

When Paul Blackburn died in the fall of 1971, all of his company, young and old, felt a sickening, an impact of blank, gray loss. I don't know what we hoped for, because the cancer which killed him was already irreversibly evident - and he knew it far more literally than we. But his life had finally come to a heartfelt peace, a wife and son so dear to him, that his death seemed so bitterly ironic.

Recalling now, it seems we must have first written to one another in the late forties, at the suggestion of Ezra Pound, then in St. Elizabeth's Hospital. We shared the same hopes for poetry, the same angers at what we considered its slack misuses. Paul was without question a far more accomplished craftsman than I and one day, hopefully, the evidence of his careful readings of the poems I sent him then will be common information. We finally met at his place in New York in the late spring of 1951, just prior to my moving with my family to France. He was the first poet of my generation and commitment I was to know, and we talked non-stop, literally. for two and a half days. I remember his showing me his edition of Yeats' Collected Poems with his extraordinary marginal notes, tracking rhythms, patterns of sounds, in short the whole tonal construct of the writing. He had respect then for Auden, which I did not particularly share, just that he could use him also as an information of this same intensive concern. He was already well into his study of Provençal poetry, which he'd begun as a student in Wisconsin, following Pound's direction and, equally, his insistence that we were responsible for our own education.

As it happened, we shared some roots in New England, Paul having lived there for a time with his mother's relatives when young. But the Puritanism he had to suffer was far harsher than what I had known. For example, his grandmother seems to have been classically repressed (her husband, a railroad man, was away from home for long periods) and sublimated her tensions by repeated whippings of Paul. He told me of one such time, when he'd been sent to the store with the money put in his mitten, on returning he'd stopped out front and the change, a nickel, somehow slipped out into a snowdrift. And as he scrabbled with bare hands trying to find it, he realized his grandmother was watching him from behind the curtains in the front room - then beat him when he came in. Those bleak Vermont winters and world are rarely present directly in his poems, but the feelings often are, particularly in his imagination of the South and the generous permission of an unabashed sensuality.

At one point during his childhood, a new relationship of his mother's took him out of all the gray bleakness to a veritable tropic isle off the coast of the Carolinas. I know that his mother, the poet Frances Frost, meant a great deal to him - and that her own painful vulnerabilities, the alcoholism, the obvious insecurities of bohemian existence in the Greenwich Village of her time, pervade the experience of his own sense of himself. His sister's resolution was to become a nun.

Paul's first marriage was finally a sad shock to me, just that I could never accept the fact of the person to whom he'd committed himself. She is the "lady he had known for years" in "The Decisions," and one hopes she did find the "new life" that cost him so much. The antagonisms felt by her and my own wife provoked an awful physical battle between Paul and me one night, when we were all living in Mallorca (he was about to spend a year in Toulouse on a Fulbright), and for some years thereafter we didn't see each other, although we had wit enough, thankfully, to keep the faith sufficient to let me publish Paul's first book of poems, The Dissolving Fabric (1955).

During the sixties I was able to see Paul quite frequently, although he lived in New York and I was usually a very long way away. He and his wife, Sara, were good friends to us, providing refuge for our daughter Kirsten on her passages through the big city, and much else. Sara, characteristically, was able to get publication for another close friend's writing (Fielding Dawson, An Emotional Memoir of Franz Kline, Pantheon, 1967), thanks to her job with its publisher. Elsewise Paul certainly did drink, did smoke those Gauloises and Picayunes, did work at exhausting editing and proofing jabs for Funk & Wagnalls, etc., etc. It's a very real life.

The honor, then, is that one live it. And tell the old-time truth. Of course there will be human sides to it, but Paul would never argue that one wins. To make such paradoxic human music of despair is what makes us human to begin with. Or so one would hope.

Buffalo, New York

November 25,1979

from Against the Silences, by Paul Blackburn. The Permanent Press, London and New York, 1981. Online Source

Robert M. West

Blackburn, Paul, (24 Nov. 1926-13 Sept. 1971), poet and translator, was born in Saint Albans, Vermont, the son of William Blackburn and Frances Frost, a poet and novelist. Blackburn's parents separated in 1930. His father left for California; his mother pursued a literary career, eventually settling in New York City's Greenwich Village. Blackburn was left in the care of his strict maternal grandparents. His grandmother required little pretext for whipping him regularly, and his grandfather, who worked for the railroad, was away from home for long stretches at a time. In late poems such as "My Sainted," he reveals his bitterness about his early childhood.

However, Blackburn is primarily a poet of New York City life, and his contact with the New York literary scene came early. At age fourteen he joined his mother in Greenwich Village, where she lived with her lover, Paul's "Aunt" Carr. The bohemian environment was much more conducive to his creativity than life with his grandparents had been. His mother encouraged his interest in poetry, and Blackburn later acknowledged that her gift of W H. Auden's Collected Poems was particularly helpful in giving him "a formal sense of musical structure." Blackburn entered New York University in 1945, but he left to join the army the following year.

In 1947 Blackburn reentered NYU, where he studied poetry under M. L. Rosenthal, who later became one of his most enthusiastic admirers. He served briefly as the editor of the Apprentice, the school literary magazine. It was here that Blackburn began reading Ezra Pound, who proved to be an enormous influence on him. In 1949 he transferred to the University of Wisconsin, where he graduated with a B.A. in 1950.

While studying at Wisconsin, Blackburn occasionally hitchhiked to Washington, D.C., to see Pound at St. Elizabeths Hospital. Pound helped Blackburn secure his first major publication, "The Innocents Who Fall Like Apples," in James Laughlin's New Directions Annual (1951). On Pound's advice Blackburn began corresponding with Robert Creeley, which developed into an important friendship. Blackburn's first book of translations, Proensa (1953), and his first book of original poems, The Dissolving Fabric (1955), were published by Creeley's Divers Press.

In his preface to Blackburn's Against the Silences (1980), Creeley acknowledges that Blackburn was "a far more accomplished craftsman." Of their first meeting Creeley writes, "I remember him showing me his edition of Yeats's Collected Poems with his extraordinary marginal notes, tracking rhythms, patterns of sounds, in short the whole tonal construct of the writing." Throughout his career other poets praised Blackburn highly for his understanding of the craft. In Big Table (Spring 1960), Paul Carroll wrote, "I don't suppose any poet our age handles a single line, a stanza, a whole poem with his skill and grace."

Friendship with Creeley led to contact with poets Charles Olson, Jonathan Williams, and Denise Levertov. Blackburn shared with them the ideas about poetry most notably articulated by Olson in his 1950 essay "Projective Verse." Their goal was a new musicality for modern poetry, which they believed suffered from the ascendancy of the metrical foot over the syllable and the breath. They felt a poet could correct this unhealthy emphasis by using the standardized spacing of the typewriter. A poem could be scored like a piece of music to preserve the poet's unique breath. Blackburn was adept at this technique, adjusting line breaks, margins, and spacing to reflect his desired reading pace and breathing patterns. Olson's gathering of Creeley, Williams, and others at Black Mountain College in North Carolina resulted in this approach becoming known as Black Mountain poetry. Blackburn, who remained in New York, always resisted the label "Black Mountain poet." He did, however, work briefly in the early 1950s as the New York distributor of Creeley's magazine Black Mountain Review. To support himself during the 1950s and 1960s he also worked a variety of jobs, including editing encyclopedias and writing book reviews.

Despite his inclusion in Donald Allen's influential anthology The New American Poetry (1960), for years Blackburn remained a little-known figure who continued to publish through small presses. His second book of original poetry, Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit (1960), contains some of his most memorable poems, including "Clickety-Clack" and "The Once-Over." Here, as in many of his poems, Blackburn plays the semidetached observer: "Clickety-Clack," for example, wryly describes an outrageous pass he makes at a woman on the subway. The Nets (1961) and two limited-edition books followed. Not until The Cities (1967), his first book issued by a major publisher, did Blackburn gain widespread attention. The only other full-length book of his poems to appear during his lifetime was In, on, or about the Premises (1968).

Chief among Blackburn's longer works are The Selection of Heaven (1980) and The Journals (1975). The Selection of Heaven, a mysterious poem commemorating both the death of his paternal grandparents and the breakup of his second marriage, was completed by 1967. The Journals, a record of the last four years of his life, including his stoic response to the cancer diagnosed in late 1970, has been faulted for its documentary quality. However, in a review for Parnassus (Spring-Summer 1976), poet Gilbert Sorrentino argues that The Journals represents a pinnacle, not a relaxation, of Blackburn's art: "That the poems seem, often, the thought of a moment, a brilliant or witty or dark response to still-smoking news, is the result of his carefully invented and released voice, a voice that we hear singing, virtuoso."

Blackburn published poems in little magazines constantly throughout his career. A prolific poet, at his death Blackburn had published or arranged for the publication of the 523 poems found in his Collected Poems, and he had written approximately 600 more. Of his eighteen books of original poetry, five were published posthumously.

In addition to writing poetry, Blackburn spent considerable time translating. Frustrated by his inability to read Provençal passages in Pound's epic poem the Cantos, Blackburn began to study that language. This led to his translations of the troubadours, collected in Proensa (1953; expanded ed. 1978). In 1954 his study of Provençal resulted in a Fulbright fellowship to the University of Toulouse, a city he satirizes in his poem "Sirventes." In 1956 Blackburn moved to Spain, where he bought a copy of poet Federico Garcia Lorca's Obras Completas. His translations from it were collected posthumously as Lorca / Blackburn (1979). His translations also include Poem of the Cid (1966), Julio Cortázar's Blow-Up and Other Stories (1968), Cortázar’s Cronopios and Famas (1969), and Pablo Picasso's Hunk of Skin (1968).

Blackburn's translations of the troubadours are provocative and have elicited both high praise and sharp criticism. Much of the debate has centered around their vernacular, occasionally vulgar, language. In an interview with the New York Quarterly (repr. in The Journals), Blackburn said that a translator must "be willing (& able) to let another man's life enter his own deeply enough to become some permanent part of his original author." Blackburn believed that the translator should strive for clarity above all else and should not fret over his inability to render into English the ambiguities present in the original text: "Let him approach polysemia crosseyed, coin in hand." Blackburn advised the translator to avoid the stiffness and artificiality that often accompany strict translation: "Occasionally, an adaptation will translate the spirit of the original to better use than any other method ... Much depends upon the translator (also upon the reader)."

Blackburn was enormously generous to others and did much to create a mutually supportive community of poets in New York City. Newcomers found him ready to help them publish, give readings, find jobs, and locate places to stay. He moved the readings at Le Metro Café to St. Mark's Church-in-the-Bowery, where in 1966 he helped establish the Poetry Project (which in 1991 celebrated its twenty-fifth anniversary with the publication of the anthology Out of this World). From 1964 to 1965 Blackburn ran a radio show dedicated to poetry. His interest in the individual poet's unique breath led Blackburn to tape the many readings he attended and to popularize poetry recordings. In 1967 he won a Guggenheim fellowship, and he taught at the State University of New York at Cortland from the fall of 1970 until his death.

Despite the increasing readership Blackburn enjoyed at the end of his life, as well as the steady flow of posthumous publications, his poetry has yet to receive the attention his advocates believe it deserves. Aspects of his work that may contribute to this inattention include his frequent obscenity and his treatment of women, which to the feminist reader may seem unpleasant or even cruel. Renewed interest in formalist poetry after his death was probably also detrimental. Perhaps Blackburn's most significant legacy is his sizable contribution to the popularization of poets and of the art of poetry.

Paul Blackburn was married three times: to Winifred Grey from 1954 to 1963 (they had been separated since 1958); to Sara Golden from 1963 to 1967; and to Joan Miller, with whom he had his only child, from 1968 until his death. He died of cancer of the esophagus in Cortland, New York.

Blackburn's papers and recordings are in the Paul Blackburn Archive of the Archive for New Poetry at the University of California, San Diego. Kathleen Woodward, Paul Blackburn: A Checklist (1980), is the best single bibliography of Blackburn's writings. The Collected Poems of Paul Blackburn, ed. Edith Jarolim (1985), is the definitive collection of Blackburn's poetry. Selected volumes include The Selected Poems of Paul Blackburn, ed. Jarolim (1989), and Clayton Eshleman, The Parallel Voyages (1987), which offers forty-eight previously unpublished poems that span Blackburn's career. Jarolim's introduction to the Collected Poems and her entry on Blackburn in the Dictionary of Literary Biography together provide a reasonably detailed biographical treatment. Notable assessments of Blackburn's career include M. L. Rosenthal, "Paul Blackburn, Poet," New York Times Book Review, 11 Aug. 1974, and Marjorie Perloff 's review of Collected Poems, repr. in her book Poetic License (1990). An obituary is in the New York Times, 15 Sept. 1971.

From American National Biography. Ed. John A. Garraty and Mark C. Carnes. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. Copyright © 1999 by the American Council of Learned Societies.

Bob Holman

Just A Moment: Paul Blackburn and the

Fragmentation of the New American Poetry

Dateline: 8/4/98

“It's a Martian thing. You wouldn't understand.”

--Paul Beatty

You can sit in the I can't call it a park, let's just call it a triangle, the one created by Stuyvesant and 9th and the fence round St. Mark's-in-the-Bowery, tipping into Second Ave. and find yourself In. On. Or About the Premises ("being a small book of poems"). The premises are of course Paul Blackburn's, the map the poem “The Slogan.” The Church, did it break Paul's heart, is the question, and No, is the answer.

Paul Blackburn is the subtle father of the Poetry Project at St. Mark's Church, the pre-spirit. Three trees were planted outside the Parish Hall near 11th Street, the one dedicated to Blackburn growing next to Frank O'Hara's, who died in 1966, the year the Poetry Project was founded, with the third dedicated to Wystan Hugh Auden, who was a parishioner at St. Mark's, often heard coughing in a back pew. Ted Berrigan's tree grows there now, as does Michael Scholnick's. The subtle father left a vision that grows as trees do.

In the early 60s, at Mickey Ruskin's Deux Magots and later at a coffee shop on Second between 9th and 10th called the Metro, Blackburn ran a poetry reading series that included as regulars Beats, New York School poets, Deep Imagists, Black Mountaineers, Umbra poets, Patarealists, and 2nd Ave poets, among others. He wielded a big bucket, and had a way of standing so that to get in, you'd either be squeezed or drop something in. “Something for the poets?” he'd say. The different groups coexisted because Paul knew how to do it.

This was the flowering of the coffeehouse poetry scene. Paul would go from reading to reading, hauling his jumbo public-high-school issue Wollensak reel-to-reel, recording open and featured readings all over town. At night, he'd record jazz or rock off the radio, or read (rewrite?) his own poems on tape. He was a walking exponent of the oral tradition. His tapes, collected at the University of California at San Diego Library, are a document of an era, with the word at the center and poets breathing them in and out.

Blackburn held court long afternoons at McSorley's, this before the word “writing workshop” was invented. There he embodied what was to become the definition of what the Church, especially through the “workshops” of Alice Notley and Bernadette Mayer, would be: a place to inspire, not define.

First the Poem.

Then, the Theory.

But back at the Metro, the center wasn't holding. A minimum was instituted: 25 cents, the price of a cuppa. A Goldwater poster appeared on the wall. Blackburn's sensibility, the owner of the cafe's lack of sensitivity, the changing of an era. . . . In 1965, LeRoi Jones led a walkout and The New American Poetry fragmented.

The rest is the end of history.

online source: http://poetry.miningco.com/arts/poetry/library/weekly/aa080498.htm

Jerome Rothenberg

I have drunk my white wine and worked

I have lasted it out into silence

( Paul Blackburn)

Like other important American poets of his time, his work reflected an identification with the initial experiments of Pound & Williams, buttressed in his case by resources of language that opened to a still larger range of European and Latin American predecessors. A Vermonter by birth, he lived most of his life in New York City, but traveled from there early & late, to chart the world through a succession of poems that were his ongoing journal (= day book), culminating in a final diaristic work appropriately called The Journals (posthumously published: 1975), of which The Net of Place [included in Poems for the Millennium] is a part.

While he was a chronicler thereby of the desiring, often thwarted mind - his own & others' - the central focus of his art was, as he saw it, a devotion to the quirky music language made: what the ear heard joined to what the eye saw. In this he early followed Pound into a search for means & sources in the troubador poetry of medieval Provence (the gathered work is called Proensa), surpassing the older poet in the voice he gave to his translations. (Or, translation aside, in the modern send-ups / variations of that voice in his own poems.)

Skeptical by nature, he clung still to a belief in poetry as both a private & communal act, a sense of which pervades his nearly final poem - "evening fantasy" - in its imagining of poets dead before him, gathered in a kind of paradise-of-poets. (His "Phone Call to Rutherford" is addressed to William Carlos Williams, following the older poet's second stroke & subsequent aphasia.)

For all his reticence in framing a poetics, Blackburn's recognition, circa 1960, of a new "American duende" was a summons - a rallying cry - for many with whom his work was intersecting.

from Poems for the Millennium. Copyright © Jerome Rothenberg and Jacket magazine 2000. Online Source

Return to Robert Blackburn