On "Memphis Blues"

Stephen E. Henderson

If the poet presents the blues through indirection in "Cabaret," in "Memphis Blues" he presents them through the matrix of the oral tradition which helped to shape their growth. The poem partly draws upon the traditional notion of "preaching the blues" found in both music and oral literature, but significantly it is not a parody of the sermon but a brilliant exploration of the song-sermon form in which the blues are historically and formally grounded. Its A-B-A form is a common song pattern and is shared by jazz and the sonata form. It is also the pattern which typical sermons take--text, development and application, repetition. In the poem the enveloping sections are historical parallels to the present:

Was another Memphis

Mongst de olden days,

Done been destroyed

in many ways....

Dis here Memphis

It may go ....

The persona cites the dangers:

Floods may drown it;

Tornado blow;

Mississippi wash it

Down to sea--

Like de other Memphis in

History.

That is the warning of apocalypse, the sign of the Judgment. The poem is a blues sermon on the Last Judgment. The language evokes the hymns of Blind Willie Johnson, the Texas preacher who sang and played in blues style and tonality:

See the sign of the Judgment

Yes, yes I

See the sign of the Judgment

Oh, yes, my Lord,

Time is drawing nigh!

And the stage is set.

The long middle section of the poem consists of six stanzas, each posing the ultimate question in the life of a Christian--Where will you be on the day when God sends down Judgment? It is the Dies Irae--Day of Anger, Day of Judgment, and a central theme of Western literature and art. One recalls the medieval plays Everyman and The Castle of Perseverance, and the other moralities which address the theme in a form comprehensible to the common man in fourteenth-century England. One remembers, too, Marlowe's Dr. Faustus imploring the heavenly spheres to cease and bring time to a halt. And who can forget the peal of the Dies Irae as it strikes fear and repentance into the heart of Goethe's Gretchen?

Most of the old-time preachers were probably ignorant of Goethe and the Faust legend, but they knew the Bible fairly well, especially the Book of Revelations, and the most gifted of them knew enough history to draw lessons from it and to incorporate them into their sermons. Their knowledge was matched if not surpassed by superb rhetorical skills. The love of language was rooted in their culture. They sang as their parents had sung: "My Lord, what a mournin'/ When the stars begin to fall." They sang: "Run, sinner, run and find yourself a hiding place." They admonished their congregations to work on the "building" for the Lord. They warned the gambler, the dancer, the drunkard, the "cussin' man," and the whoremonger to work on the building too, for the day was coming when "God's gonna separate the wheat from the tares." They questioned the sinner in his headlong flight: "O whar you runnin', sinner?" They asked him: "Sinner, what you goin' to do/When de devil git you?" And there would be nowhere for the sinner to go, for "there's no hiding place down here." Brown builds the middle section of his poem on the pattern of these songs of the Last Judgment, a pattern which is also used in the sermon. That pattern is reinforced by a smaller rhetorical pattern of concentrated and compressed Black cultural experience, a mascon, and in choosing it the poet goes to the ambivalent heart of the Black man's Christian heritage. He is both Christian and Black. He is a child of God, yet not a man. There are contradictions, and conflicts, but one kind of resolution is found in the blues. However, the blues lie outside the church, are the devil's music. Still the blues came out of the church, as the singers themselves say. Thus there is no contradiction in the development of the poem. The first person to be addressed in the "Judgment Day pattern" is the Preacher Man--

Watcha gonna do when Memphis on fire,

Memphis on fire, Mistah Preachin' Man?

And the Preachin' Man replies:

Gonna pray to Jesus and nebber tire,

Gonna pray to Jesus, loud as I can,

Gonna pray to my Jesus, oh, my Lawd!

This is correct Christian behavior and the language and sentiments echo the Judgment Day spirituals cited above. Had the poet continued in this vein, the poem might have ended with a tonality and structure akin to the sermon-poems of James Weldon Johnson. But the poem is to be an experiment in blues tonality, as the title suggests, and we are not disappointed. Something remarkable and subtle begins to happen with the introduction of this answering refrain. For one thing, the poet has established perhaps the most characteristic pattern of Black oral/musical tradition, the call-and-response, and both parts of the pattern take delightful variations of rhythm, tone, and diction as the poem proceeds. Each variation in the "call" is like a chord change, which is developed by the "response."

Although tonally and thematically the first response recalls the spirituals, the rhythm is jazzy as in gospel music. In addition, a closer examination will reveal that the call-and-response pattern is enhanced by the familiar mascon qualities of the call and the anaphora of the response. The pattern also contains an artfully concealed extension of the blues form in which the two lines of the call constitute, in effect, the first two lines of a blues stanza, while the response is a rhetorical elaboration of the third line. However, instead of the quick turn or the punch line of the blues stanza, the response stretches out into a kind of jazz melody.

Although each "change" is distinctive, we remain in the same key, as it were, as the calls are made in sequence to the Preachin' Man, the Lovin' Man, the Music Man, the Workin' Man, the Drinkin' Man, and the Gamblin' Man. Each responds in his own way, in his own rhythm and accent, but all end up with the refrain "oh, my Lawd!" first spoken by the Preachin' Man. This expression not only links the personae together, it allows for ironic variation of tone from the religious somberness of the opening section. In effect, the "Lawd" of the spirituals is subtly transformed by the "Lawd" of the blues.

The call also is a kind of blues riff which is not only found in blues songs but in other areas of the oral tradition. Thus Big Bill Broonzy sings a song called "Honey O Babe" in which these lines appear:

Whatcha gonna do when the pond goes dry, honey, honey?

Whatcha gonna do when the pond goes dry, babe, babe?

Whatcha gonna do when the pond goes dry?

And the response is:

Sit up on the bank and watch the poor things die, Honey, O babe o' mine.

Novelist John O. Killens recalls a chant which children of his generation sang in Americus, Georgia. The first line is the call; the second, the response:

Watcha gonna do when the world's on fire?

Run like hell and holler, "Fire!"

And Blind Lemon Jefferson sang, when John Killens was a little boy:

Watcha gonna do when they send your man to war?

Watcha gonna do--they send your man to war?

It is important, then, to realize that the call is a fundamental feature of blues style, and this particular call is one of the most deeply engrained in the oral tradition. This realization helps us to understand the structure of "Memphis Blues" and the reason that the title is justified. Each individual call, we may note further, is a kind of compressed blues experience, for the blues are a poetry of challenge and confrontation, and this fact is reflected in the poem's thematic concerns and its structure--its stanzas, its imagery, its rhythm, its diction, its overall shape.

In Memphis, Furry Lewis sings:

Whatcha gonna do, your troubles get like mine?

Whatcha gonna do, your troubles get like mine?

The wordless response comes ringing in from the guitar, but one ever-present possibility occurs in the response of another song:

Get a handful of sugar and a mouthful of turpentine.

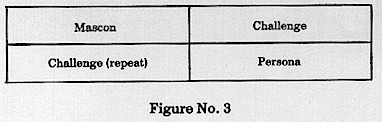

Again, diagrams help one to appreciate the poet's skill in the construction of "Memphis Blues." Each of the six stanzas of the middle section possess the following structure. First is the call, which is a kind of "riff" that may be diagramed as follows:

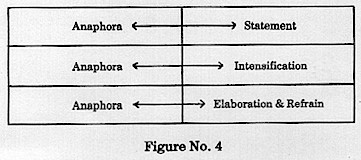

Next is the response, which may be diagrammed thus:

As Figure No. 3 dramatically demonstrates, the call is rather rigid, with a kind of singsong rhythm, characteristic of certain ritual language and of children's song. That quality is heightened by the repetition of the challenge. Variation is achieved and the poem is activated by changing the specific challenge in each call and, of course, by addressing a different persona. So we may list these elements in order: (1) "Memphis on fire," Preachin' Man; (2) "tall flames"--a variation--Lovin'Man; (3) "Memphis falls down," Music Man; (4) "de hurricane," Workin' Man; (5) "Memphis near gone," Drinkin' Man; and (6) "de flood roll fas'," Gamblin' Man. We may note that the poet achieves coherence in the call by specific mention of Memphis in calls 1, 3, and 5, and by citing the destructive forces of nature in 2, 4, and 6.

It is the response, however, in which we best see the skillful work in the poem. The anaphora builds up a driving, jazzy pattern which the second part of the line develops into a series of brilliant explorations of the melodic variety of Afro-American speech. In the first, the preacher's voice reaches a tender intensity when he prays to "my Jesus," with the initial fillip of "oh, my Lawd!" In the second, the Lovin' Man in a sensual stammer of alliteration is "gonna love my brownskin better'n before," and the emphasis is not on his being a "do right man," but on the miracle of "my brown baby," which parallels the language of the preacher. One of the most felicitous of the responses is the third, in which the poet sets up a rocking rhythm that suggests the piano's bass line, then suddenly shifts into a lovely scattering of treble notes. Here is the entire stanza:

Watcha gonna do when Memphis fall down,

Memphis falls down, Mistah Music Man?

Gonna plunk on dat box as long as it soun',

Gonna plunk dat box fo' to beat de ban',

Gonna tickle dem ivories, oh, my Lawd!

When questioned about the hurricane, the Workin' Man in the fourth stanza makes a heroic personal response which is crucial to an appreciation of the tone and significance of the entire poem. He will not give up, and he will not be content with praying. He'll put the buildings back again, to stand, and he takes pride in his energy, his will, and above all in his style: "Gonna push a wicked wheelbarrow, oh, my Lawd!" Even the Drinkin' Man will go down in style with his "pint bottle of Mountain Corn," and the stopper in his hand. Finally, we come to the Gamblin’ Man:

Watcha gonna do when de flood roll fas',

Flood roll fas', Mistah Gamblin'Man?

Gonna pick up my dice fo' one las' pass--

Gonna fade my way to de lucky lan',

Gonna throw my las' seven--oh, my Lawd!

At this point we realize that the language of the poem in these six blues vignettes reflects Black life's emphasis upon style. That emphasis is at times overlooked and frequently misunderstood although it has attracted considerable attention from the media as well as the scholarly community. In effect, the style or the styling is an assertion of meaningfulness, not of frivolity or illusion, although there are, of course, assertions which may be so classified. An examination of the last response, then, is in order. The Gamblin' Man is not going to panic and fall down on his knees and beg God for mercy. That would be the coward's way. It would also be very "unhip." Death is final, but he meets it with a gambler's nerve, which is a kind of courage. He's not going to the Promised Land, but to the "lucky lan'," which he has created out of his own life, his own experience and values. He does not live in illusion and he takes responsibility for his life. The same thing applies to the Drinkin' Man, probably the most unsavory character of the group. Even he is going out in style: "Gonna get a mean jag on, oh, my Lawd!" These are not poor, benighted, superstitious foundlings in the hands of Fate, as Jean Wagner, for example, interprets Sterling Brown's characters, but ordinary blues people heroic in their own way. As for the Drinkin' Man, we understand him better when we recall Bill Broonzy's words: "I'm gonna keep on a drinkin'/Till good liquor carry me down." Note that it's good liquor and "Mountain Corn," made by experts for virtuoso drinkers. And lurking behind the response are the immortal lines: "I got the world in a jug, the stopper's in my hand." So sang Bessie Smith.

These last stanzas of the group prepare us for the return to the somber theme of mutability in the final section of the poem:

Memphis go

By Flood or Flame;

Nigger won't worry

All de same--

Memphis go

Memphis come back

Ain' no skin

Off de nigger's back.

All dese cities

Ashes, rust....

De win' sing sperrichals

Through deir dus'.

What warrants attention here is the loaded ambiguity of the last two lines, which one can read as an equation of the spirituals with the moaning of the wind, or as an existential projection of human value upon "objective," impersonal nature. And the songs are spirituals, not the blues, nor yet the songs of Tin Pan Alley, and the people have made them out of the substance of their lives, bleak though they might have been. An affirmation is made out of their courage, their strength, and their resilience, but equally out of their faith in themselves and their style. So when one reexamines the poem with the haunting lyricism of its enveloping sections and the artful mastery and development of folk resources in the middle, one wonders why it has not received its critical due. And one has to conclude that some of the fault, at least, can be attributed to a patronizing attitude toward the folk themselves, whom the poem celebrates.

From "The Heavy Blues of Sterling Brown: A Study of Craft and Tradition." Black American Literature Forum (1980).

Joanne V. Gabbin

In "Memphis Blues," Brown uses folk rhymes, working in concert with "the rhythm and imagery of the black folk sermon," to convey "the black folk preacher's vision of the threat of destruction" and a deeper, more pervasive "comment on the transitory nature of all things man-made." Charles H. Rowell recognizes Brown's "excellent employment of the rhythm of black folk rhymes" to emphasize the speakers' indifference to the inevitable destruction of Memphis . . . ."

As Rowell suggests, Brown, projecting on the speaker a child's indifference to death, uses playful, teasing, lines to heighten the poem's message. The Black man is indifferent to the destruction of Memphis, for he has never seen it as his own.

In part two of "Memphis Blues," Brown employs the call and response patterns of certain spirituals to create voices similar to the folk preacher's exhorting his congregation to salvation and those of the members responding to his call.

[ . . . .]

Here, however, is a difference. "Ironically, the response of each speaker in the poem has nothing to do with the impending destruction; while Memphis is being destroyed, each speaker plans to do what he thinks is best for him. " Implicit in their responses is "the sensibility of the blues singer--his stoic ability to transcend his deprived condition." Also present is the blues song's emphasis "on the immediacy of life, the nature of man, and human survival in all of its physical and psychological manifestations." The preacher man, the drinking man, the gambling man, and so on, see themselves as outsiders. As they have been excluded from the society by proscription and prejudice, they define their survival in their own terms; they take their pleasure and their meaning from within the boundaries set for them. However, moving at a deeper level is Brown's paradox. Being outside will not keep them from destruction. Even those distinctions made and boundaries set among men will have no meaning then.

As Brown brings into play a combination of folk forms--the secular rhyme, the sermon, the blues, and the scattered notes of the gospel shout--in "Memphis Blues," they function not only to further the meaning of the poem but also to suggest the essential interrelatedness of the forms.

From Sterling A. Brown: Building the Black Aesthetic Tradition. Copyright © 1985 by Joanne V. Gabbin.

Mark A. Sanders

With a striking vision of apocalyptic retribution, [in] "Memphis Blues" natural and political calamity hold center stage. Yet another folk voice asserts its vision and agency as it identifies the temporal nature of Western civilization and thus of white hegemony. In the larger scheme of things, both modern and ancient Memphis signify the same mutability in human endeavors; edifices constructed in a futile gesture toward immortality, both cities must remain subject to God's destructive wrath. Although the poem never cites God or Christianity directly, its African American emphasis on Old Testament types and judgment is obvious. First listing Old Testament cities of sin and Hebrew or Israelite slavery, the poem begins to position the modern African American relative to transhistorical oppressive forces. The destruction of Nineveh, Tyre, and Babylon serves as evidence of God's justice, as these cities refused to listen to God's will. Thus they were judged and condemned. In the context of the poem, they stand as prelude to contemporary circumstances. Through natural catastrophe, an Old Testament God wreaks his revenge on a people too evil to follow his commandments.

[ . . . .]

As these rapidly paced lines quickly conflate past and present, they implicitly reiterate the analogy between Old Testament Israelites and modern African Americans. Both structure and statement also establish a critical tension with the ensuing section, one highlighting a folk response to the inevitable apocalypse. In contrast to the declarative statement of part 1, the dialogic approach of part 2 portrays interracial conversations in response to calamity. Brown appropriates the form and mode from a spiritual, "What You Gonna Do?," which Howard Odum and Guy Johnson collected in Negro Workaday Songs:

Sinner, what you gonna do

When de world's on fi-er?

Sinner, what you gonna do

When de world's on fi-er?

Sinner, what you gonna do

When de world's on fi-er?

O my Lawd.Brother, what you gonna do? etc.

Sister, what you gonna do? etc.

Father, what you gonna do? etc.

Mother, what you gonna do? etc.

The spiritual, by implication, implores the sinner to seek salvation in anticipation of the coming judgment. "Memphis Blues" replicates the same sense of urgency and inevitability but stresses consistency, rather than transformation:

Watcha gonna do when Memphis on fire,

Memphis on fire, Mistah Preachin’ Man?

Gonna pray to Jesus and nebber tire,

Gonna pray to Jesus, loud as I can,

Gonna pray to my Jesus, oh, my Lawd!

The preacher continues to preach; the lover continues to pursue, and the gambler continues to bet, all in direct contrast to cataclysmic change. The final stanza makes explicit the dichotomy between mutability and permanence, inferring black continuity in the midst of God's wrath:

Memphis go

By Flood or Flame;

Nigger won’t worry

All de same--

Memphis go

Memphis come back,

Air’ no skin

Off de nigger's back.

All dese cities

Ashes, rust....

De win’ sing sperrichals

Through deir dus’.

In the midst of desolation "de win’ sing sperrichals," signaling an African American presence beyond God's judgment and one independent of (perhaps transcending) hegemonic forces. Here, the cultural dynamic within the poem is spiritual, but the poem itself asserts a blues inflection, indeed a blues ballad used for even greater dramatic effect in "Ma Rainey." But here, as we have seen in section one, the blues process itself asserts the ability of specific personas to envision being free or beyond circumscription.

From Afro-Modernist Aesthetics and the Poetry of Sterling Brown. Copyright © 1999 by The University of Georgia Press.

Return to Sterling A. Brown