Hart Crane: Illustrated Editions of The Bridge

The Walker Evans photographs of 1930

Publication of the first edition of The Bridge in 1930 was also the occasion for the debut of Walker Evans as a photographer. Photos by Evans, in fact, appeared in not only the deluxe limited edition released in March from the Paris-based Black Sun Press (directed by Harry and Caresse Crosby) but also the trade edition published in New York in April by Horace Liveright and reprinted in a second impression in July. Moreover, each of these printings had its own exclusive photos or photo. However different these photos were from one another, they had one feature in common: all were designed to exoticize the Brooklyn Bridge – to emphasize its "modernist" angularities, its resemblances to other more aggressively modern examples of architecture like the skyscraper. As photographed in several pictures by Evans, the bridge sometimes looked like an abstract design, or a web of radiant lines, or a hard-edged form-follows-function machine, or a perch from which distant objects lost their familiar outlines, or a mysterious frame that left a dark slash across remote Manhattan towers. It looked, that is, like anything but the familiar object, completed in 1883, that efficiently carried pedestrian traffic, trolleys, and automobiles across the East River.

No doubt this presentation of a defamiliarized Brooklyn bridge was intentional. New Yorkers in 1930, if asked to nominate their best example of a handsome piece of modern architecture, would more likely have turned to the recently-completed Chrysler building or possibly the Woolworth building of 1913. Brooklyn Bridge, opened in 1883, was nearly half a century old. To view the Bridge as an artifact that was "modern" required some aggressive reconceptualization. Of course it is not Crane’s intent to celebrate that which is simply modern or radically new. The Bridge is explicit on this point: both the subway and the airplane (or "aeroplane," as Crane spelled it) brought problems with them that offset any of their innovative value. The Brooklyn Bridge was offered as an example that negotiated a position midway between tradition and novelty, the stable and the exploratory. And that, in fact, was what it also represented architecturally, as Alan Trachtenberg notes. Responding to a critical review by Montgomery Schuyler in 1883, in which Schuyler scorns (among other things) the flatness of the roof at the top of each pier, Trachtenberg explained that Schuyler was pointing to

something significant about the bridge. Unavoidably, it embodies two styles of building: the masonry, good or bad, is traditional, while the steel is something new. To be recognized as architecture, structural stone must be carved into a familiar shape, while the steel, unburdened with precedents, could take whatever shape its function demanded. (Brooklyn Bridge: Fact and Symbol, pp. 87-88)

The Brooklyn Bridge itself stood at a midway point between old and new. It could represent, then, by invoking itself as an example, the value and propriety of "connection," of continuity.

Evans’s pictures, however, portray an object that is more stylish than anything else, an object that hovers dramatically outside any definition that portrays the bridge as inherently mediating. Indeed, it is not until the third photo that an identifiable outline of the Brooklyn Bridge emerges. And even then, when that third photo is compared with original negative it reveals that Evans has cropped out of the published photo the wooden walkway that was visible in the original. That walkway served to anchor the lamppost that now floats mysteriously to the right of the photo.

Further helping to present images that seem at once estranged from any obvious referent is the markedly diminished size of each photo. When the Crosbys lured Crane to the Black Sun Press they did so by promising an edition that would appear (as Crane boasted) "on sheets as large as a piano score, so none of the lines will be broken" (letter of 26 February 1929 to Charlotte and Richard Rychtarik). The Crosbys obliged with a page that measured a generous 8½ by 10½ inches. If so large a page necessarily emphasizes the small size of the photos, so notable a proportional difference must have been intended. The photos were reproduced in sizes that were actually smaller than their original negatives (which were 2½ by 4 ¼ inches): more precisely, the first photo is 1¾ by 3 1/16 inches, the second is 1¼ by 2 5/8 inches and the third is 2¼ by 3 inches. These were not photos that were blown up but shrunk down.

The images they offer, then, are dramatically obscure. Among the photographs Evans retained from this period can be found several that were taken at the same time as the photograph selected to be the first. These were snapped from a position exactly below the bridge, at water level, as a tug slides by with a ship alongside. In all of these, the underside of the bridge cuts a dramatic swathe down the exact center of the photo, but in some, that underside is a background against which puffs of smoke appear. In others, the prow of a ship is visible as it emerges against the distant pier on the Manhattan side. The photograph that was chosen from all these, however, was one which most withheld the identifying characteristics of the ship passing beneath.

Of all the photos it is the second whose obscurity suggests deliberate wit. The Bridge isn’t part of the picture, we realize, because we stand on the Bridge to look down as a tugboat ferries a load of railroad hopper cars. But that image is remarkably abstract as it cuts a broad diagonal across the front of the photo. The flatness of the image is especially striking. Anything like a graceful or dynamic presence is definitely missing. Nevertheless, we now, in fact, are standing on the very Bridge that symbolizes grace and dynamics.

That very Bridge is at last on display in the third photo, but even here there is as much abstraction in the photograph as there is a straightforward set of references. The double towers reveal arches that are suggestively phallic. The cables of the bridge become nets. The lamppost floats as if detached from any ground. Evans had photos that were more patently representative – a shot of the South Street piers with the skyscrapers of Manhattan in the distance, glimpsed through the distinctively twined cables of the bridge – but the photos that were chosen were themselves conspicuously angular and modernistic, deliberately nonreferential. Their modernism lent itself to the Brooklyn Bridge.

We do not know who chose these particular photos for either the Black Sun Press or the Liveright trade editions. All the principals with any say in the matter – Crane and Evans as well as Harry and Caresse Crosby – happened to be together in New York City in the fall and early winter of 1929 when the decisions were being made. No occasion arose in which an exchange of letters might occur, leaving a written record of a decision. About the exact positioning of the three photos, however, we have Crane’s explicit instruction to Caresse Crosby in a 26 December 1929 letter (after a sensational suicide by Harry early in December – a double suicide, actually, in which he and a sexual soul-mate expired together). Since Caresse had vowed to go on with the press, and the first order of business was concluding work on The Bridge, Crane wrote to her:

By the way, will you see that the middle photograph (the one of the barges and tug) goes between the "Cutty Sark" section and the "Hatteras" section. That is the "center" of the book, both physically and symbolically. Evans is very anxious, as I am, that no ruling or printing appear on the pages devoted to the reproductions – which is probably your intention anyway. (O My Land, My Friends, 421)

What Crane assures with this placement is the adjacency of image to text, photograph to poem. Indeed, Evans’s portrayals of the bridge could not get any closer to the physical words of the poem. His first photo stands directly across from the opening stanzas of "Proem: To Brooklyn Bridge" and his last photo stands directly across from the closing stanzas of "Atlantis," while the middle photo waits by itself, surrounded by white pages on either side, midway between two sections of The Bridge. With no explanatory text, they are presented as if they might seamlessly blend into the experience of reading. But everything about these photographs suggests that they might easily be invited into the depths of Crane’s poems. The Bridge as it appears within them, especially if we take the photos sequentially, appears only gradually; it is an evocative piece of architecture that these photographs are able to work with; and while it eventually reveals itself as an actual thing upon which persons might actually walk, it remains hauntingly and suggestively abstract, as if it could be allied with a number of other objects – as if it was also functioning as a metaphor.

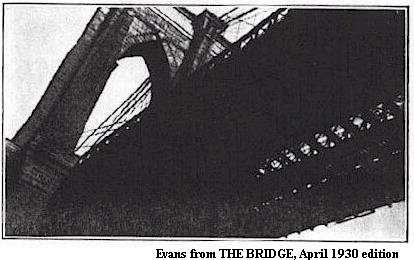

In a 1972 essay on these three photos, Gordon Grigsby claimed a resemblance between them and the work of Alfred Stieglitz. Pointing out Crane’s admiration for Stieglitz (whom Crane had met on returning to New York in 1923), Grigsby describes the Evans photographs as "hard, somber, finely arranged compositions, almost classical in the clarity and restraint of their aesthetic" (5). Evans was not, however, a fan of Stieglitz, who had given Evans’s work a cursory glance when he made a pilgrimage to his studio. In 1929, as he wrote to a friend, it was the work of Paul Strand that struck him as most impressive. Was it Evans, then, who, when choosing the photo that would appear in the first trade edition, deliberately sought out an example that was decidedly less "classical" in its "clarity and restraint"? The photo that forms the frontispiece to the first impression published in New York in April 1930 stands in stark contrast to the Black Sun Press photos.

This version of the bridge, insofar as it is wildly adventuresome, seems designed

to put to rest any doubts that the Brooklyn Bridge might be a suitably modern artifice.

Its startling angle from below, its aggressive truncation of the topmost edge of the arch,

its hint of powerful girders all suggest this bridge is an almost defiantly modern piece

of work, more aesthetic than utilitarian, more sculpture than roadway. The photo conceives

the bridge as launched into space. The dark line that surrounds the photo, as well as the

unusual and somewhat dramatic placement of the photo at the very top of the page (in

direct alignment with the border on the title page) further underscores a vivid, eccentric

dynamics.

This version of the bridge, insofar as it is wildly adventuresome, seems designed

to put to rest any doubts that the Brooklyn Bridge might be a suitably modern artifice.

Its startling angle from below, its aggressive truncation of the topmost edge of the arch,

its hint of powerful girders all suggest this bridge is an almost defiantly modern piece

of work, more aesthetic than utilitarian, more sculpture than roadway. The photo conceives

the bridge as launched into space. The dark line that surrounds the photo, as well as the

unusual and somewhat dramatic placement of the photo at the very top of the page (in

direct alignment with the border on the title page) further underscores a vivid, eccentric

dynamics.

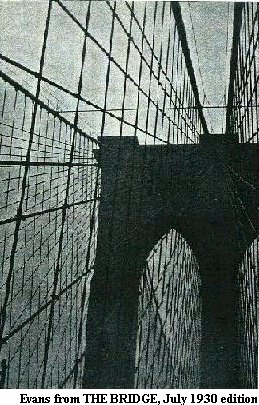

If this frontispiece was eccentrically dynamic, then was the frontispiece to the second impression an attempt to adjust for that? And why was another new photo required for the second edition (which appeared in July 1930).

Here is a composition that is the most securely balanced of all, mixing elements

of identifiability with aspects of defamiliarization. At 4 by 6 inches, it is also the

largest of the illustrations, the only photo to be expanded from the original, almost

double the size of the negative (by contrast the previous photo was almost exactly the

size of the negative). The arches of the bridge occupy the lower quarter of the photo, and

the interior space formed by a left-hand arch registers itself in a strong upward thrust,

against which the supporting cables of the bridge become visible as a skein of nets that

play themselves out both near and far. Here the architectural power of the bridge is

perhaps most evident. The lamp post in the third Black Sun Press photo, while acting to

insert a note of delicacy against the heft of the twin black arches, also invited a sense

of scale into the photo, thus suggesting that the bridge might also be a space in which to

walk. This July 1930 version emphasizes grandeur over pedestrian accessibility through

selective cropping. Originally, the photo offered not only a glimpse of the wooden walkway

beneath the arches but also the catenary system through which the trolleys received

electrical power. With these details cropped out of the lower ten percent of the photo,

the bridge appears to rise effortlessly against the sky, as if following the prompt of its

upthrusting – and defiantly phallic – arch. (A trace of the catenary remains in

that enigmatic pole rising out of the bottom left of the photo.)

Here is a composition that is the most securely balanced of all, mixing elements

of identifiability with aspects of defamiliarization. At 4 by 6 inches, it is also the

largest of the illustrations, the only photo to be expanded from the original, almost

double the size of the negative (by contrast the previous photo was almost exactly the

size of the negative). The arches of the bridge occupy the lower quarter of the photo, and

the interior space formed by a left-hand arch registers itself in a strong upward thrust,

against which the supporting cables of the bridge become visible as a skein of nets that

play themselves out both near and far. Here the architectural power of the bridge is

perhaps most evident. The lamp post in the third Black Sun Press photo, while acting to

insert a note of delicacy against the heft of the twin black arches, also invited a sense

of scale into the photo, thus suggesting that the bridge might also be a space in which to

walk. This July 1930 version emphasizes grandeur over pedestrian accessibility through

selective cropping. Originally, the photo offered not only a glimpse of the wooden walkway

beneath the arches but also the catenary system through which the trolleys received

electrical power. With these details cropped out of the lower ten percent of the photo,

the bridge appears to rise effortlessly against the sky, as if following the prompt of its

upthrusting – and defiantly phallic – arch. (A trace of the catenary remains in

that enigmatic pole rising out of the bottom left of the photo.)

Unlike the three photos in the Black Sun Press, the two that appeared in the different impressions of the trade edition were positioned as frontispieces, at a traditional distance from the text. They were arranged, then, to serve a useful illustrative function, to acquaint an audience with some physical features of the Brooklyn bridge while at the same time introducing angles of approach that removed the bridge from its utilitarian setting and suggested its affinity with other works of art, with pieces of sculpture. What the three photos of the Black Sun Press edition built toward in their final photo – an image of the arches and cables of the bridge after photos that pointedly evoked the bridge without depicting it – was presented at the outset in the trade edition in a more conventional understanding of the value of the illustration.

The Joseph Stella Frontispiece

|

Photograph of the canceled title page of the Black Sun Press edition |

Crane was quick to register his pleasure in the three photos of the Black Sun Press edition, professing delight in a letter of 2 January 1930 to Caresse Crosby: "I think Evans is the most living, vital photographer of any whose work I know. More and more I rejoice that we decided on his pictures rather than Stella’s" (O My Land, 422). This "Stella" whose picture had been passed over in favor of Walker Evans’s photographs was no less than the celebrated young modernist painter Joseph Stella (1865-1946), one of the Europeans who had brought news of cubism and futurism to New York art circles and had prospered as a result. And originally, it was a work by Stella that Crane had in mind when, shortly after first meeting the Crosbys in January 1929, the idea of a deluxe limited edition of The Bridge was first discussed.

Crane had began the year 1929 as a 30-year-old tourist, traveling in Europe on a $5,000 bequest from his grandmother’s estate. The change of scene, he no doubt hoped, would prod him into completing The Bridge, most of which had been written in a few months in 1926, when he had taken himself away from the distractions of New York City to live for a summer and part of a fall on the Isle of Pines in the Caribbean. What remained elusive was a last segment exactly at the midpoint of the long poem which had, ever since the work had been outlined in 1926, centrally involved Whitman, a figure who was, for one circle of Crane’s friends, out of fashion. Allen Tate and Yvor Winters, in their mid-20s and still developing the moral formalism that would be their signatures, recoiled from Whitman’s sprawling observations as undisciplined threats to the body politic. By contrast, the circle of Crane’s friends that centered around cultural and social critic Waldo Frank (which included Alfred Stieglitz and Eugene O’Neill) revered Whitman as an iconoclast whose own social program glimpsed an America united in its diversity. And even Further complicating Crane’s attitude toward Whitman was the underground status he shared with him as a gay male poet – a status that he would acknowledge but with subtlety.

In short, the most difficult section Crane had left for last – a situation not untypical of a career in which his own knack for mishandling matters was sometimes impossible to separate from his writing strategies. When he was starting to write The Bridge he had worked on the uplifting conclusion that would eventually be entitled "Atlantis" much as he had begun Voyages by composing what would become "Voyages IV," the very moment of ecstatic sexual union. To complete Voyages, he eventually surrounded that fourth poem with an opening narrative of expectation and a concluding narrative of loss. With The Bridge, however, he had raised the stakes for his own project by positing a triumphant finale whose basis he would then need to construct in the poems of the main text. It is not possible to conclude that Crane wrote well under pressure simply because he was always finding himself in situations in which he could not but write under pressure. To contract for a deluxe, illustrated, limited edition might have seemed to him just the kind of serious incentive that would help him to finish.

The Black Sun Press was certainly capable of delivering such an edition. Begun in 1927 as "a show case for writers as yet unknown or distrusted by commercial publishers" (according to Harry Crosby’s biographer Geoffrey Woolf [Black Sun, p. 174]), the press had, by 1929, published brief collections of poetry by Archibald MacLeish (Einstein, 1929), stories and novellas by D. H. Lawrence (Sun, 1928; The Escaped Cock [later titled The Man Who Died], 1929), and lavishly illustrated reprints of stories by Poe and Wilde. The writer whose work it had most completely presented, however, was Crosby himself. His work had been featured as the first volume with the imprint of the press (Shadows of the Sun, 1928), and his works continued to appear in considerable numbers: Transit of Venus (1928), Mad Queen (1929), Shadows of the Sun – Series Two (1929), Sleeping Together (1929). (That so much of his work was self-published helps explain why his reputation as a poet has been so long in forming.) To add Hart Crane’s name to this list, to publish an advance edition of a major work, could only benefit the press, and Crosby was, whatever other foibles he pursued, serious about his press. Even though the press had proved useful to the Crosbys, as Woolf explains, because it "offered them immediate and easy access to literary personages they might otherwise never have met" (Woolf, p. 174), it was never a frivolous venture: "Generally resentful of business obligations, Harry tended scrupulously to the most minute detail of his books" (Woolf, p. 175).

When Crane began talking with the Crosbys in January 1929 about a Black Sun Press Bridge, he already had an idea of how to illustrate it. A few months before, in the summer of 1928, Crane had been visiting an old friend, Charmion von Wiegand Haubicht, in her summer home at Croton-on-Hudson, New York, and she had drawn his attention to a brief essay in which Stella addressed aesthetic possibilities of the Brooklyn Bridge and associated himself intimately with it. Stella’s little sketch, "The Brooklyn Bridge (A Page of My Life)," was remarkably aligned with Crane’s own thoughts. Stella envisioned the bridge much as Crane had: as a point of vantage that was both deeply within the city yet giving one the potential to see beyond that city. Its unique perspective encouraged one to be both the searching. Probing explorer and the visionary standing on a brink:

Many nights I stood on the bridge – and in the middle alone – lost – a defenseless prey to the surrounding swarming darkness – crushed by the mountainous black impenetrability of the skyscrapers – here and there lights resembling suspended falls of astral bodies or fantastic splendors of remote rites – shaken by the underground tumult of the trains in perpetual motion, like the blood in the arteries – at times, ringing as alarm in a tempest, the shrill sulphurous voice of the trolley wires – now and then strange moanings of appeal from tug boats, guessed more than seen, through the infernal recesses below – I felt deeply moved, as if on the threshold of a new religion or in the presence of a new DIVINITY.

Even Stella’s delicately frenetic and slightly breathless style – its fragments set in giddy motion by the dashes that both link and separate them – would have appealed to Crane, who frequently seemed in his own prose just to stop short of employing capital letters himself, even as he personally favored the suspenseful dash.

Stella’s bridge, like Crane’s, was mysteriously empowered to solve social problems: "… from the sudden unfolding of the blue distances of my youth in Italy, a great clarity announced PEACE – proclaimed the luminous dawn of A NEW ERA." As with Crane’s poetry, the "bridge" evoked here existed outside and beyond any single description: it was nothing less than a mechanism or a medium through which the aspirations of the individual became artistically charged, like a lighting-rod for aesthetic sensibility. Stella even associated his bridge with some of the same American poets whom Crane championed, though they were out of favor with his modernist friends. On the one hand, the dark city the Bridge evoked was linked by Stella with "POE’s granitic, fiery transparency revealing the swirling horrors of the Maelstrom" and on the other, it was "the verse of Walt Whitman – soaring above as a white aeroplane of Help – was leading the sails of my Art through the blue vastity [sic] of Phantasy …" (Stella’s wildly mixed metaphor of Whitman’s "soaring aeroplane" leading art’s "sails" may have served as a germ for Crane’s own "Cape Hatteras," the poem on Whitman that Crane sketched in Europe as his central section.)

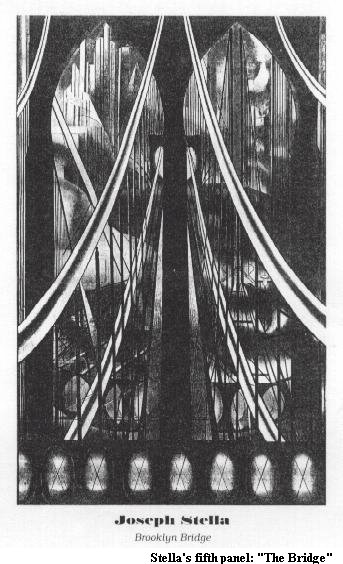

Given these striking parallels, it is not surprising that Crane’s

thoughts would have turned to Stella when offered the chance to think of an illustration

for his long poem. After all, Stella’s little essay had been printed on the occasion

of displaying a large-scale enterprise entitled New York Interpreted which was in

itself a painterly analogue to the symphonic epic: a piece in five panels, the central one

of which (entitled "Skyscrapers") stood 4 ½ feet tall and more than eight feet

wide (the four side panels were each slightly narrower, but still over seven feet wide).

The fifth of these panels was entitled "The Bridge" and depicted New York

skyscrapers framed through the archways of what could only be the Brooklyn Bridge.

Although Stella’s meditation on the Brooklyn bridge had been originally prompted by

thoughts of an earlier painting, a work in the cubist style completed in 1919 and entitled

"Brooklyn Bridge," Stella’s essay, in the form in which Crane knew it,

accompanied not a reproduction of that 1919 painting but his 1923 polyptych New York

Interpreted. This, then, was the painting – the fifth of the five panels –

that Crane first envisioned as his frontispiece, a clear parallel in numerous respects to

his own work:

large-scale enterprise entitled New York Interpreted which was in

itself a painterly analogue to the symphonic epic: a piece in five panels, the central one

of which (entitled "Skyscrapers") stood 4 ½ feet tall and more than eight feet

wide (the four side panels were each slightly narrower, but still over seven feet wide).

The fifth of these panels was entitled "The Bridge" and depicted New York

skyscrapers framed through the archways of what could only be the Brooklyn Bridge.

Although Stella’s meditation on the Brooklyn bridge had been originally prompted by

thoughts of an earlier painting, a work in the cubist style completed in 1919 and entitled

"Brooklyn Bridge," Stella’s essay, in the form in which Crane knew it,

accompanied not a reproduction of that 1919 painting but his 1923 polyptych New York

Interpreted. This, then, was the painting – the fifth of the five panels –

that Crane first envisioned as his frontispiece, a clear parallel in numerous respects to

his own work:

In the same January 1929 letter to Stella requesting permission to reproduce this painting, Crane demonstrated his enthusiasm for Stella’s essay by soliciting it for publication in Transition, the European journal edited by Eugene Jolas, an important figure in the European avant-garde who had been hospitable to Crane’s writing, along with reproductions of three panels from New York Interpreted. Stella’s essay, along with the reproduction of the fifth panel only, "The Bridge," appeared in issue no. 16-17, dated June 1929.

The similarities between Crane’s cultural epic and Stella’s polyptych are striking enough to lead at least one scholar to wonder whether Crane had been more intimate with Stella’s painting than he had been willing to acknowledge. After all, Stella had painted not one but two "portraits" of the Brooklyn Bridge, and both were objects of considerable admiration in New York art circles in the early 1920s. How could Crane have not known about them? Stella’s biographer, Irma B. Jaffe has assembled a persuasive narrative that suggests Crane’s project was likely to have been powerfully influenced by these examples from Stella. For Jaffee, Crane’s January 1929 letter to Stella seems disingenuous, especially the statement: "It is a remarkable coincidence that I should, years later, have discovered that another person, by whom I mean you, should have had the same sentiments regarding Brooklyn Bridge which inspired the main theme and pattern of my poem."

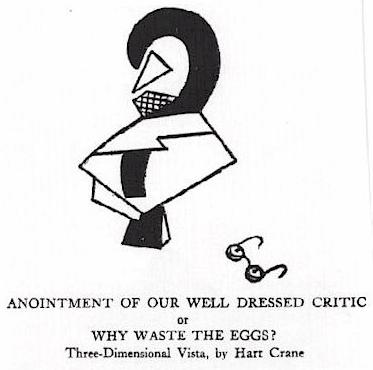

Stella’s name ought to have been familiar to Crane, as Jaffe notes.

Few contemporary artists in New York had achieved the success of Stella in actively

promoting the tenets of cubism and futurism. More important, Stella’s work circulated

in the very magazines in which Crane hoped to publish and with which he was associated.

Indeed, the special "Stella number" of the Chicago-based Little Review in

August 1922 (volume nine, number one, though misidentified on its title page as volume

nine, number three) happened to be the journal for which Crane had served as Advertising

Manager in 1919 – without much success, though he did persuade his father to take out

an advertisement for Crane’s Chocolates.  Moreover,

Crane himself had appeared in the issue after the "Stella number" with a

satirical sketch, "Anointment of the Well-Dressed Critic," that indicates how

carefully Crane wanted to keep pace with modernist art: his cartoon is a question mark

that is surrounded by cubist-like distortions.

Moreover,

Crane himself had appeared in the issue after the "Stella number" with a

satirical sketch, "Anointment of the Well-Dressed Critic," that indicates how

carefully Crane wanted to keep pace with modernist art: his cartoon is a question mark

that is surrounded by cubist-like distortions.

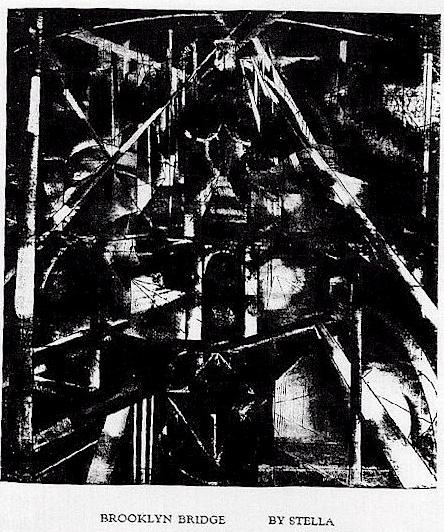

Among the paintings that were reproduced in the "Stella issue" was the 1919 "Brooklyn Bridge." If Crane had even glanced at the issue of the Little Review that featured Stella wouldn’t his eye have been at once caught by this painting on what would be a subject of immense importance to him? Is it possible that Stella is a foundational source for The Bridge – a fact that Crane is surreptitiously acknowledging in 1929 by arranging to have included within the first edition a Stella painting, albeit not the painting that had been the origin of the long poem?

If Crane had spotted that painting in 1922 – and it is worth

mentioning that it is one of a number of muddy black-and-white reproductions scattered

throughout the issue in three separate sections – he never did register his excited

reaction to it in any of his letters of the time. What can be said that might link this

first depiction of Brooklyn Bridge by Stella and the conception of Crane’s new poem

is the element of generality that attends both. Stella’s 1919 painting is less a

portrayal of the actual Brooklyn Bridge (despite its title) than a formally organized

presentation of a cubist construction.  Abstract lines predominate, and the presence

of the Brooklyn Bridge and the modern city is conspicuously downplayed, though the pair of

arches that are directly centered in the painting clearly resemble the distinctive granite

towers of the Brooklyn Bridge with their Gothic arches reminiscent of cathedral windows.

(To the right is the 1919 Stella painting as reproduced in the Little Review in

black-and-white.)

Abstract lines predominate, and the presence

of the Brooklyn Bridge and the modern city is conspicuously downplayed, though the pair of

arches that are directly centered in the painting clearly resemble the distinctive granite

towers of the Brooklyn Bridge with their Gothic arches reminiscent of cathedral windows.

(To the right is the 1919 Stella painting as reproduced in the Little Review in

black-and-white.)

Just as Stella’s painting subordinates the presence of an actual bridge to a demonstration of cubist principles, so Crane’s earliest conceptions of his new long poem, entitled The Bridge, never refer specifically to Brooklyn Bridge and always emphasize the generalities of "bridging." In his earliest descriptions of his new project, Crane first describes The Bridge as an extension of "Faustus and Helen," the three-part sequence he had completed in January 1923 when he had returned from New York and was living in Cleveland. In followup letters of February and March, he continues to refer to the bridge in terms that are exclusively metaphorical. If he had been thinking of any particular bridge, it is likely he had in mind an earlier poem, an unpublished fragment entitled "The Bridge of Estador," some portions of which he had cannibalized for two other poems, "Praise for an Urn" and "Episode of Hands," and a copy of which he sent to Gorham Munson on April 1921. "Estador" was no more (or less) "real" as a place than Xanadu. The poem opens with lines that will act as a refrain: "Walk high on the bridge of Estador, / No one has ever walked there before."

Crane quoted a handful of lines from his new poem in a letter to Allen Tate, but these too envision the bridge as primarily metaphorical, no less unreal or mystical than the bridge of Estador because this bridge (in lines later reproduced as the opening to "Van Winkle") leapt "From Far Rockaway to Golden Gate," uniting the continent.

In these earliest of conceptions, the bridge was carefully left disembodied – as befits, perhaps, the "mystical synthesis of America" that he promised to Gorham Munson in early 1923. But even after Crane left Cleveland in the spring of 1923 and returned to New York, he continued to add to his description of a bridge that was exclusively metaphorical. He sent some examples of his new writing back to friends in Cleveland, Charlotte and Richard Rychtarik. These were drafts of what would eventually become "Atlantis"; never once did he explain to them that he was inspired by a particular bridge or Brooklyn bridge.

Is there a moment when the association between The Bridge and Brooklyn Bridge suddenly occurred? It probably came about

|

as late as the spring of 1924, when Crane took up residence in the Opffer family household at 110 Brooklyn Heights, well within sight of the Brooklyn Bridge itself – and indeed in the very location from which Joseph Roebling oversaw its construction. But Crane’s new interest in the Brooklyn Bridge was not based on an aesthetic appreciation of it as an artifact so much as on his new association with Emil Opffer. Falling in love with Opffer, moving to Brooklyn Heights, beginning work again on The Bridge all occur at the same time. His emotional repositioning is at once a physical repositioning which affords him a new slant on his work: "For the first time in many weeks I am beginning to further elaborate my plans for my Bridge poem," as he writes to his mother on May 11, 1924. Even here, however, he is not yet linking Brooklyn Bridge to The Bridge, but that linkage is about to occur in a more candid letter to Waldo Frank on April 21, 1924, which announces his new love affair and which begins: "For many days, now, I have gone about quite dumb with something for which ‘happiness’ must be too mild a term." Crane further mentions "the ecstasy of walking hand in hand across the most beautiful bridge in the world, the cables enclosing us and pulling us upward in such a dance as I have never walked and never can walk with another." As Samuel R. Delany points out, the shadows of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1924 would have allowed for exchanges of same-sex affection that permitted such physical displays. Moreover, sailors in the Brooklyn Navy Yard would have used the bridge as a pathway to the South Street taverns and bars. (This would have been a background Crane drew upon for the barroom scene and the homeward walk in "Cutty Sark.") But if Crane personalizes and eroticizes Brooklyn Bridge, he also insists upon its function as a generalizing symbol, promising to Waldo Frank that his faith in Crane’s art will be repaid as Crane’s skill as an artist evolves: "Then we shall take a walk across the bridge to Brooklyn (as well as to Estador, for all that!)" (187).

This April 21, 1924, letter is the first in which Crane directly mentions Brooklyn Bridge, but in it he also retains a sense of that actual artifact as a metaphorical construct. Nevertheless, the linchpin that is the true uniting source is the personality of Emil Opffer, the great love of Crane’s life, long-known as the muse of Voyages and almost certainly serving a similar role for much of The Bridge. When the Brooklyn Bridge appears in Crane’s poem, it is not simply a contemporary artifact that is aesthetically attractive even as it retains its functionality, and it is not simply an example of the virtue of "connecting," of reaching out and extending oneself to others: it is also a secret talisman, a hidden souvenir that points to a love inscribed everywhere but never mentioned. The specificity of the Brooklyn Bridge is not simply a "presence" so much as it is a metonym for the figure of Emil Opffer.

If Crane had seen Stella’s 1919 "Brooklyn Bridge" reproduced in The Little Review in 1922, then, it is unlikely that he would have responded to it as particularly special. Not only had he not yet begun his long poem, but he had little reason to associate Brooklyn Bridge with New York. When he had previously lived in New York City from 1916 to 1919, his addresses were in Manhattan, though sometimes in lower Manhattan near the Brooklyn Bridge. Had he seen Stella’s painting he might have, at best, associated it only with his general sense of bridging and bridges – the same sense from which he produced his earliest drafts of what would become "Atlantis."

return to Hart Crane