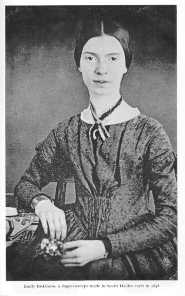

Emily Dickinson's Life

Paul Crumbley

Dickinson's

poetic accomplishment was recognized from the moment her first volume appeared in 1890,

but never has she enjoyed more acclaim than she does today. Once Thomas H. Johnson made

her complete body of 1,775 poems available in his 1955 variorum edition, The Poems of

Emily Dickinson, interest from all quarters soared. Readers immediately discovered a

poet of immense depth and stylistic complexity whose work eludes categorization. For

example, though she frequently employs the common ballad meter associated with hymnody,

her poetry is in no way constrained by that form; rather she performs like a jazz artist

who uses rhythm and meter to revolutionize readers' perceptions of those structures. Her

fierce defiance of literary and social authority has long appealed to feminist critics,

who consistently place Dickinson in the company of such major writers as Anne Bradstreet,

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Sylvia Plath, and Adrienne Rich.

Dickinson's

poetic accomplishment was recognized from the moment her first volume appeared in 1890,

but never has she enjoyed more acclaim than she does today. Once Thomas H. Johnson made

her complete body of 1,775 poems available in his 1955 variorum edition, The Poems of

Emily Dickinson, interest from all quarters soared. Readers immediately discovered a

poet of immense depth and stylistic complexity whose work eludes categorization. For

example, though she frequently employs the common ballad meter associated with hymnody,

her poetry is in no way constrained by that form; rather she performs like a jazz artist

who uses rhythm and meter to revolutionize readers' perceptions of those structures. Her

fierce defiance of literary and social authority has long appealed to feminist critics,

who consistently place Dickinson in the company of such major writers as Anne Bradstreet,

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Sylvia Plath, and Adrienne Rich.

Dickinson was born 10 December 1830, in Amherst, Massachusetts, where she lived until her death from Bright's disease on 15 May 1886. There she spent most of her life in the family home that was built in 1813 by her grandfather, Samuel Fowler Dickinson. His role in founding the Amherst Academy in 1814 and Amherst College in 1821 began a tradition of public service continued by her father, Edward, and her brother, Austin. All the Dickinson men were attorneys with political ambitions; the Dickinson home was a center of Amherst society and the site of annual Amherst College commencement receptions. The effect of growing up in a household of politically active, dominant males can be heard in Dickinson's 1852 letter to her close friend and future sister-in-law Susan Gilbert during a Whig convention in Baltimore: "Why can't I be a Delegate to the great Whig Convention?--dont I know all about Daniel Webster, and the Tariff and the Law?" As the confidence and frustration of this letter attests, the Dickinson family tradition had prepared the poet for a life of political activity and public service, only to deny her that life because of her sex.

By the time she wrote this letter, Dickinson had graduated from Amherst Academy and completed a year of study at Mount Holyoke. Though she was referred to by her close friend Samuel Bowles as "the Queen Recluse" in an 1863 note to Austin, her life was not nearly so sheltered as these terms imply; the "Queen" portion of Bowles's appellation should perhaps receive the greater emphasis. Accounts of her earliest years with Austin and her younger sister Lavinia depict a healthy, happy girl whose precocious intelligence did not prevent her from enjoying a normal childhood. From the time she started school, Dickinson distinguished herself as an original thinker who, in her brother's words, dazzled her teachers: "Her compositions were unlike anything ever heard--and always produced a sensation--both with the scholars and Teachers--her imagination sparkled--and she gave it free rein."

During the 1847-1848 year she spent studying under Mary Lyons at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, Dickinson acquired limited notoriety as the one student unwilling to publicly confess faith in Christ. Designated a person with "no hope" of salvation, she keenly felt her isolation, writing her friend Abiah Root in 1848, "I am not happy, and I regret that last term, when that golden opportunity was mine, that I did not give up and become a Christian." In 1850, she would share similar sentiments with her friend Jane Humphrey: "Christ is calling everyone here, all my companions have answered, even my darling Vinnie believes she loves, and trusts him, and I am standing alone in rebellion."

Such resistance to conversion at a time when friends and family were making public confessions reflects a lifelong willingness to oppose popular sentiment. The experience at Mount Holyoke may well have brought to the surface an independence that fueled Dickinson's writing and led her to cease attending church by the time she was thirty. Following her return to Amherst in 1848 and after the religious awakening that peaked there around 1850, she began to write seriously. The magnitude of her output was not clear until after her death, when her sister Lavinia discovered a cherry-wood cabinet containing some 1,147 poems in fair copy. In the meantime, Dickinson increasingly withdrew from public view, participating in commencement receptions but little else after the early sixties. Despite her withdrawal, however, she maintained correspondence with a wide community of friends and associates, including such well-known literary figures as Helen Hunt Jackson. The 1,150 letters in The Letters of Emily Dickinson, edited by Thomas H. Johnson and Theodora Ward in 1958, represent a fraction of what she actually wrote.

Much critical attention has been devoted to the years of Dickinson's greatest poetic production, when her output is estimated to have accelerated from 52 poems in 1858 to 366 poems in 1862, and then declined to 53 poems in 1864. What provoked such a sudden and rich abundance of creativity? And why did Dickinson take the time to carefully gather fair copies of 1,147 poems and bind 833 of them in the individual packets known as the fascicles? Early scholarship sought evidence of a failed love interest in the late fifties to account for this sudden burst of energy. Speculation about her possible lovers has at one time or another touched on almost every person for whom she felt deeply, from her brother, her sister-in-law Susan Gilbert, and her friend Kate Scott Anthon, to Charles Wadsworth, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Samuel Bowles, and Judge Otis Lord. These various studies reveal that Dickinson felt great passion for her family and friends and that at times her feelings were distinctly sexual. There is no solid evidence linking her romantically to anyone.

Most recent scholarship has abandoned the search for Dickinson's romantic inspiration. Finding in the poetry the reflection of a complex, multifaceted mind, critics have hesitated to simplify her achievement by inscribing it within a single master narrative. Though the suddenness and the intensity of Dickinson's most productive years still excites scholarly interest, the focus has shifted from questions related to motive and origin to those concerned with style and practice. The fascicles, especially, together with Dickinson's refusal to publish when she had ample opportunity in later life, have provoked close examinations of both her manuscripts and her communication with other literary figures.

The likelihood that updated variorum and readers' editions of the poems will shortly appear has intensified debate over the way Dickinson's writing should appear in print. As scholars explore methods for translating her chirography onto the printed page, more is learned about the range of possible readings suggested by her fair copies. Respecting Dickinson’s punctuation, use of variants, and lineation will have a major influence on the way her poems are read and understood. Feminist scholarship has convincingly demonstrated her resistance to patriarchal authority and stimulated interest in the revolutionary nature of the self presented in her work. With the advent of the Emily Dickinson Journal (1992), students of her poetry gained an invaluable tool for monitoring these and other issues that characterize a rapidly expanding field of research.

Major collections of Dickinson manuscripts are located at the Houghton Library of Harvard University and the Jones Library at Amherst.

From The Oxford Companion to Women’s Writing in the United States. Copyright 1995 by Oxford University Press, Inc.

Jane Donahue Eberwein

Dickinson, Emily (10 Dec. 1830-15 May 1886), poet, was born Emily Elizabeth Dickinson in Amherst, Massachusetts, the daughter of Edward Dickinson, an attorney, and Emily Norcross. The notation "At Home" that summed up her occupation on the certificate recording her death in that same town belies the drama of her inner, creative life even as it accurately reflects a reclusive existence spent almost entirely in the Dickinson Homestead. That home, built by her grandfather Samuel Fowler Dickinson, represented her family's ambition. Edward Dickinson's young family shared the Homestead first with his parents and (after Samuel Fowler Dickinson's financial collapse as a result of overextending his resources on behalf of Amherst College) with another family before moving in 1840 to the home on North Pleasant Street where Emily spent her adolescence and young womanhood. In 1855 Edward Dickinson celebrated the family's renewed prosperity by repurchasing the Homestead, where Emily Dickinson remained until she died. Although her father and grandfather held prominent places in the town as lawyers and college officers, it is indicative of changing reputations that the Homestead is maintained today by Amherst College as a memorial to this woman, who has become an American legend for the poems she wrote in its kitchen pantry and in her second-story chamber. Like the "Circumference"-seeking songbird of one of her poems, Dickinson is now as much "At home--among the Billows--As / The Bough where she was born--" (Poems 798 [P798], p. 604).

Dickinson grew up in a Connecticut Valley environment that drew close linkages among religion, intellectual activity, and citizenship. She studied at Amherst Academy, then greatly influenced by the scientist-theologian Edward Hitchcock of Amherst College, and worshiped at the First Church (Congregational) during the period of revivalistic evangelical Protestantism known as the Second Awakening. Her father played an active role in the town's political and business affairs, served as treasurer of the college, and was a leading figure in the church community even though not actually converted and eligible for membership until the revival of 1850. Her mother had joined the church when pregnant with Emily, her second child. The poet had an older brother, William Austin, and a younger sister, Lavinia, as well as a close circle of girlhood friends.

Letters written during Dickinson's one year at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary (1847-1848) reflect tendencies evident even in her academy years: maintenance of close family ties and intense friendships with chosen intimates, preference for solitude over society, intellectual curiosity, pride in her ability to write wittily, and hesitation to commit herself to Christ in the manner expected by her friends and spiritual counselors, including Mount Holyoke's redoubtable foundress, Mary Lyon. Those tendencies grew more pronounced when she returned home to Amherst and its lively community of young people. Although aware of local developments such as the coming of the Amherst-Belchertown Railroad and involved to some extent in reading groups and the cultural offerings of a college town, she increasingly narrowed her circle to family and a few friends--notably Susan Gilbert. When Austin Dickinson married Sue in 1856, Edward Dickinson built a house next door to the Homestead for the young couple, thereby squelching any impulses to move west. With her closest friend only a short walk away, Emily visited frequently for the next several years but apparently avoided most of her sister-in-law's ambitious social entertainments. Gradually she discontinued even those visits but retained close ties to Sue as well as to some of Sue's and Austin's friends, notably Samuel Bowles of the Springfield Republican, his assistant Josiah Gilbert Holland, and Holland's wife, Elizabeth. Shrinking from public exposure, Dickinson also ceased going to church by the early 1860s and never attempted to join it through profession of faith. Nonetheless she maintained friendships with successive ministers of the First Church while pursuing her independent spiritual journey.

Two events impelled Dickinson beyond her domestic sphere. Her father's election to the U.S. House of Representatives precipitated family visits. Although Emily remained at home with Sue and a cousin, John Graves, when her mother and Lavinia visited Washington, D.C., in 1854, she did accompany her sister to the capital the following year, staying at Willard's Hotel and visiting tourist attractions such as the U.S. Patent Office and Mount Vernon. On the return trip the sisters visited their Coleman cousins in Philadelphia, where they probably stopped at the Arch Street Presbyterian Church and met its minister, the Reverend Charles Wadsworth. In 1864 and 1865 Dickinson required treatment by a Boston specialist, Dr. Henry W. Williams, for an eye disorder. While under his care Dickinson stayed at Mrs. Bangs's Boardinghouse in Cambridge with cousins Lavinia and Frances Norcross. Upon her return to Amherst, Dickinson confined herself to the Homestead, declaring, "I do not cross my Father's ground to any House or town" (Letters 330 [L330], p. 460). Yet she kept up with current literature through extensive reading, chiefly in English and American Romantic writers, and maintained lively correspondences with many friends.

Unfortunately the record of that correspondence lapses from the mid-1850s to the early 1860s after Sue's return from teaching in Baltimore and Austin's from law school, even though that was when Dickinson wrote most of her poems. There had been some clever valentines and a few lyrics in the early 1850s as well as references in letters to Jane Humphrey and Abiah Root to some "strange things--bold things" that she had undertaken (L35, p. 95). Around 1858 she started copying poems and stitching them into little booklets now known as fascicles. These poems, remarkable for their distilled wit, ambiguous manner, and stylistic idiosyncrasies, were shared with friends but apparently not offered for publication. The ten that were printed in the Springfield Republican, in several New York and Boston journals, and in Helen Hunt Jackson's A Masque of Poets between 1852 and 1878 appeared anonymously and, it seems, without the poet's consent. Dickinson evidently valued her privacy too much to risk the fate of a nineteenth-century literary celebrity and protected herself by adhering to standards of genteel reserve imposed by society on ladies of her age and station. Nonetheless, she cultivated connections with literary figures in positions to promote her work, not only with Bowles and Holland but also with Thomas Wentworth Higginson, whom she appointed as her "preceptor" from 1862 until her death, and Helen Hunt Jackson, who had volunteered to serve as her reticent friend's literary executor because "you are a great poet--and it is a wrong to the day you live in, that you will not sing aloud" (L444a, p. 545).

Dickinson's poetry is remarkable for its emotional and intellectual energy as well as its extreme distillation. In form, everything about it is tightly condensed. Words and phrases are set off by dashes, stanzas are brief, and the longest poem occupies less than two printed pages. Yet in theme and tone her poems grasp for the sublime in their daring expression of the soul's extremities. Stylistic tendencies such as her inclination toward symbolically freighted words such as "Circumference," her ironic wit, her adoption of personae, her penchant for oxymoron ("sumptuous--Despair--" [P505, p. 387]; "Heavenly Hurt" [P258, p. 185]), her punctuation that withholds traditional syntactic markers, her omission of titles, her recording of poems in multiple versions with variant words and stanzas, her willingness to leave poems unfinished, and even the distinctive amount of white space she left on the page force readers to involve themselves directly in this poetry in a way that forecloses definitive readings even while encouraging an exceptional degree of intimacy between reader and poet. Dickinson's imagery ranged widely from domestic and garden metaphors, through geographic and scientific references drawn from her education, to literary allusions (especially to the Bible, Shakespeare, Dickens, and the Brontės). The poems express extremes of passion--love, despair, dread, and elation--and do so in many voices (that of the child, for instance, or the bride, the nobleman, the madwoman, or the corpse).

Although these lyrics characteristically withhold evidence of the occasions that precipitated them, they suggest various narratives of religious searching and of romantic love reciprocated but unfulfilled. Consequently there has been much speculation about whatever crises in Dickinson's life may have spurred her to poetic expression: literary ambition in conflict with both societal restrictions on women and her own reticent disposition, the eye problems that threatened her lifelines of reading and writing, or perhaps a religious conversion or even a psychological breakdown. Much of that speculation focuses on presumed romantic attachments to Charles Wadsworth and/or Samuel Bowles, both married men and therefore unattainable. Whether either of these men was the "Master" she addressed in three passionate letter drafts apparently written in 1858 and 1861 remains a question. The only romantic attachment that has been documented was with Judge Otis Phillips Lord, a widowed friend of her father, from the late 1870s to 1884, many years after most of her poems were written. Other candidates for the role of Dickinson's forbidden lover include Susan Gilbert Dickinson and Sue's friend Kate Scott Anthon Turner. Letters as well as poems demonstrate the intensity of the poet's engagement with her friends while leaving to the reader's imagination whatever private dramas she may have concealed when telling Higginson that "my life has been too simple and stern to embarrass any" (L330, p. 460).

We do know that Dickinson took profound pleasure in her reading, her gardening, her friendships, and her share in nurturing Austin's and Sue's three children. She also devoted herself, as did her sister, to long-term care of their invalid mother. Her life was marked increasingly by deaths within the family (her father in 1874, her mother in 1882, and her eight-year-old nephew in 1883) and in her circle of friends. Samuel Bowles died in 1878, Josiah Holland in 1881, Charles Wadsworth in 1882, Otis Phillips Lord in 1884, and Helen Hunt Jackson in 1885. She felt bereaved by deaths of favorite authors also, including Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1861), George Eliot (1880), and Ralph Waldo Emerson (1882). Grief confronted her repeatedly with religious doubts she had coped with earlier in poems exploring her "Flood subject" of immortality (L319, p. 454), though Dickinson's late writings, especially letters, suggest an increasingly hopeful sense of her relationship with God. She suffered from kidney disease, perhaps associated with hypertension, for several years before she died.

Were Emily Dickinson known only by public achievements, she would soon have been forgotten. While the poet died, however, her poems lived. Back in 1862, opening her correspondence with Higginson, she challenged that man of letters to tell whether her verse "breathed" (L260, p. 403). Lavinia Dickinson, who came upon a box with the stitched fascicles and other poetic manuscripts while settling her sister's affairs, resolved to display Emily's genius to the world and eventually enlisted Mabel Loomis Todd, a friend and their brother's mistress, to edit them. Higginson assisted with publication and promotion of Poems by Emily Dickinson (1890) and Poems by Emily Dickinson (1891). Todd alone then responded to public interest by publishing an 1894 edition of selected Dickinson letters and a third collection of Poems in 1896. Roberts Brothers of Boston brought out all four volumes, the first of which sold out rapidly with eleven editions printed within a year. A legal dispute between Lavinia Dickinson and Todd over Austin's estate then put an end to Todd's editing. No further Dickinson writings came to press until after Susan Dickinson's death in 1913, when her daughter, Martha Dickinson Bianchi, published a selection of poems her aunt had sent to her mother as The Single Hound (1914). Bianchi followed that with correspondence and biography reflecting her own sense of family tradition in The Life and Letters of Emily Dickinson (1924), personal reminiscences in Emily Dickinson Face to Face (1932), and successive volumes of poems. After Bianchi died, Todd and her daughter, Millicent Todd Bingham, brought out the remaining poems in their possession as Bolts of Melody (1945). Gradually, as public acceptance of Dickinson's writing grew, editors represented poems more in accordance with her wording, spelling, and punctuation. When Thomas H. Johnson presented The Poems of Emily Dickinson (1955) in a scholarly three-volume variorum edition, he was hailed for making her art available to readers in its full brilliance. Since then, however, Ralph W. Franklin's two-volume facsimile edition of the poet's fascicles in The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson (1981) has shown that Dickinson's lineation was often less conventionally hymnlike than it appears in Johnson's edition, that the poems occupy space in more revealing ways than can be reproduced in print, and that variants play a significantly complicating role in an inherently ambiguous, open-ended poetry that resists editorial closure while demanding reader engagement.

From the first appearance of Poems during the 1890 Christmas season, readers have responded variously to Emily Dickinson. Arlo Bates, a Boston critic, remarked ambivalently that Dickinson's poetry was "so wholly without the pale of conventional criticism, that it is necessary at the start to declare the grounds upon which it is to be judged as if it were a new species of art." Yet William Dean Howells declared that "if nothing else had come out of our life but this strange poetry we should feel that in the work of Emily Dickinson America, or New England rather, had made a distinctive addition to the literature of the world" (Buckingham, pp. 29, 78). Dispraise of her style (initially perceived as crude and unpolished) and admiration for her daring treatment of subject matter--both religious and erotic (often in one poem)--was matched by popular curiosity about the poet's life. Attention focused early on the mysteries of her seclusion, with speculation about the romantic disappointment readers typically detect in Dickinson's poetry when they construct narratives to link her lyrics (a tendency first encouraged by the Todd-Higginson editions with a section of each book devoted to "Love" poems and later by Johnson's attempt to group poems chronologically in a way that makes them look autobiographical).

Although interest in one or more lovers continues, as does attention to the poet's religious quest and to her quiet subversion of gender assumptions, Emily Dickinson's poems steadily gain recognition as works of art, both individually and collectively, especially when read in her original fascicle groupings, which establish not just her unquestionable brilliance but her frequently underestimated artistic control. The regard Dickinson has won in the little more than a century since her poems introduced her to the world has established her as the most widely recognized woman poet to write in the English language and as an inspiration, both personally and in terms of craft, to modern women writers. As a voice of New England's Protestant and Transcendental cultures in fruitful tension and of the spiritual anxieties unleashed by the Civil War (during which she wrote the great majority of her poems) and as an avatar of poetic modernism, Emily Dickinson now stands with Walt Whitman as one of America's two preeminent poets of the nineteenth century and perhaps of our whole literary tradition.

Bibliography

The two major collections of Dickinson manuscripts and other research materials are held by Harvard University's Houghton Library and Amherst College's Special Collections. Joel Myerson, Emily Dickinson: A Descriptive Bibliography (1984), records the publication history of her poems and letters. Thomas Johnson's editions of The Poems of Emily Dickinson (1955) and The Letters of Emily Dickinson (1958) remain the preferred scholarly editions, supplemented by R. W. Franklin's facsimile edition of The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson (1981). Critiques of Johnson's editing appear in Franklin, The Editing of Emily Dickinson: A Reconsideration (1967), and Martha Nell Smith, Rowing in Eden: Rereading Emily Dickinson (1992). Although Dickinson's poems and letters have been released gradually and in varying forms since 1852, the Johnson editions are generally preferred to earlier printings as representations of the poet's intent.

Documentary materials providing a context for Dickinson's life may be found in Jay Leyda, The Years and Hours of Emily Dickinson (1960), and Polly Longsworth, The World of Emily Dickinson (1990), which provides a pictorial record of the poet's environment. The most important biography remains Richard B. Sewall, The Life of Emily Dickinson (1974). Cynthia Griffin Wolff, Emily Dickinson (1986), combines biography with extensive critical analysis. Many critical studies of Dickinson attempt with varying degrees of plausibility to draw biographical insights from readings in poems, letters, and fascicle groupings. Among these are John Cody's psychobiography, After Great Pain: The Inner Life of Emily Dickinson (1971), William H. Shurr's The Marriage of Emily Dickinson: A Study of the Fascicles (1983), and Judith Farr's The Passion of Emily Dickinson (1992). Willis J. Buckingham has collected early responses to Dickinson's poetry in Emily Dickinson's Reception in the 1890s: A Documentary History (1989). Bibliographic reviews of subsequent Dickinson criticism include Buckingham, Emily Dickinson: An Annotated Bibliography--Writings, Scholarship, Criticism, and Ana, 1850-1968 (1970), and Karen Dandurand, Dickinson Scholarship: An Annotated Bibliography, 1969-1985 (1988). Joseph Duchac's two annotated guides to The Poems of Emily Dickinson trace commentary published on individual poems from 1890 to 1977 (1979) and from 1978 to 1989 (1993). Numerous articles appear in literary journals around the world, and the Emily Dickinson International Society sponsors two publications entirely focused on her work: the Emily Dickinson Journal and the Emily Dickinson International Society Bulletin.

Source: http://www.anb.org/articles/16/16-00453.html; American National Biography Online Feb. 2000. Access Date: Wed Mar 21 11:23:13 2001 Copyright (c) 2000 American Council of Learned Societies. Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

Return to Emily Dickinson