On "Often I Am Permitted to Return to a Meadow"

Cary Nelson

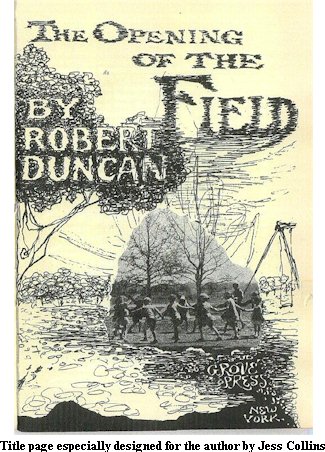

"Often

I Am Permitted to Return to a Meadow" is the first poem in The Opening of the

Field; the reader thus connects the meadow in the poem with the field in the book's

title. Field is a broad term referring to various landscapes, to the notion of a

perceptual gestalt, and to Olson's idea of composition by field. Does the shift to a

meadow signal a more specific landscape? A meadow suggests a single harmonious climate, a

space protected by its surroundings. "Opening" a field implies a liberating or

pioneering gesture, an entrance or exposure. Returning to a meadow implies the recovery of

past intimacy, the restoration of secure resources. The poem's title domesticates the

revelatory title of the book. The meadow here is a memory to be inhabited; its emotional

connotations are private and delicate. Yet we also wonder if this meadow is the field the

book would open.

"Often

I Am Permitted to Return to a Meadow" is the first poem in The Opening of the

Field; the reader thus connects the meadow in the poem with the field in the book's

title. Field is a broad term referring to various landscapes, to the notion of a

perceptual gestalt, and to Olson's idea of composition by field. Does the shift to a

meadow signal a more specific landscape? A meadow suggests a single harmonious climate, a

space protected by its surroundings. "Opening" a field implies a liberating or

pioneering gesture, an entrance or exposure. Returning to a meadow implies the recovery of

past intimacy, the restoration of secure resources. The poem's title domesticates the

revelatory title of the book. The meadow here is a memory to be inhabited; its emotional

connotations are private and delicate. Yet we also wonder if this meadow is the field the

book would open.

The poem's title is its first line, effecting a beginning in medias res that conflicts slightly with the line's strong assertion of composed renewal. The word "permitted" is a gesture of humility, undercutting any connotation of will or urgency. Almost without effort, the speaker finds himself in the presence of this meadow. . . .

These first three stanzas complete the sentence started in the title. The meadow now seems almost an imaginary hortus conclusus, an enclosed garden protected from the outside world. The setting is so "made-up," so constructed, fictional, that its otherness shows little congruence with the imagination that gave it life. Yet intimacy and otherness are inextricably part of the same texture; in the poem they echo within the same shell of sound. The partial rhyme of "mind" and "mine" reinforces the meadow's ambiguities. "Made-up" and "made place," the first implying artifice, the second solid construction, are not mutually exclusive alternatives. Similarly, "that is not mine" and "that is mine" appear to be opposite, yet visually and aurally they are mutual reverberations, alternatives reflecting one another. The very composure and perfection of this made place lend it a sense of difference, of exclusive containment. But this meadow is also the place where we always are, the mind's ground and the setting for its development. It is "so near to the heart," this otherness that constitutes the self."

The word "pasture" broadens the "meadow" of the first line. The pasture is eternal because it is so thoroughly "made-up" as to last forever and because it acquires an impersonality and universality linking it to every other "made place." It is a place, not just a thing, because its isolation is confirmed by our being there. Enfolding the pasture in the medium of thought makes it a place with "a hall therein," with an entrance and a means of passage. The pasture is the field where the mind feeds on its own substance--the human body, but the body both specific and general. Like Duncan's image of the body of primitive man, it is without preconceived outline and conscious in all of its parts. This makes the mind's energy visible, "as if it were the mind itself / which descends in the poem / and becomes manifest" (FD, 86), while also "encumbering in its concretion and weight the longing for ecstatic flight the soul knows" (C,62).

As we finish the opening stanzas, we sense an uneasiness that also hints of freedom. If forms are mere shadows, they have no special permanence. Yet Duncan will later write of "the ascendancy of the shadow / in the blossoming mass" (RB, 169), so even a transient form gives satisfaction in completed structure. Nonetheless, the structure here is also a dissolution:

Wherefrom fall all architectures I am

I say are likenesses of the First Beloved

whose flowers are flames lit to the Lady

She it is Queen Under the Hill

whose hosts are a disturbance of words within words

that is a field folded.

These next two stanzas present a conventional invocation to the muses, a gesture appropriate to the book's first poem." Again, however, the architectures "fall," and we can read this falling as a loss of variety and innocence, as well as a falling into place, as forms find their necessary order. The tone of these stanzas recalls medieval hymns to the lady and courtly love poems, but that decorous surface masks a more unsettling communication--that the poem's formal imperatives, its ordering structures, are really "likenesses" of a much wider set of verbalizations. This suggests that the poem's progress is determined by connections inscribed in the words themselves. A "disturbance of words within words," the poem is a ritual performed in the Lady's honor and in her service--"she," Duncan writes later, whose breast is in language, who "sends her own priestesses of the Boundless to these councils of our boundaries" (T, 19). A "disturbance" is any reorganization along fresh lines of association. The "field folded" is an archetype of poetic form: a field of associations doubling back on themselves to create a formal gestalt. Only within that limited frame can we glimpse "the Hosts of the Word that attend our words" (T, 19).

The result is a fiction, a dream momentarily resisting the larger pressures of the language. . . .

The dream works its changes among the grasses at the surface of the field of meanings. It troubles the depths briefly, sounding rhythms that set the poem's pace and establish its configuring image sequences. Despite its apparent originality, the poem is a variation on a codified ritual, like a children's game. The secret of this children's game is the belief (the historical truth of which is irrelevant to Duncan's purpose) that the rhyme dates back to the bubonic plague, when flowers were carried to ward off the odor of decay. Elsewhere Duncan describes poetry as an infection of meaning, a disease erupting in the body of language: "The ear / catches rime like pangs of disease from the air," he writes, "For poetry / is a contagion" (BB, 32).

With their decorous rhetoric, the last stanzas further the same notions:

Often I am permitted to return to a meadow

as if it were a given property of the mind

that certain bounds hold against chaos,

that is a place of first permission,

everlasting omen of what is.

The title is repeated and the poem brought round to its origin. But the formal resolution (like the end of the children's game) will also be a falling down. Returning to the beginning suggests that the several stanzas were only the circular unfolding of the first line, a disturbance within its words. The poem is like a first field on which we ventured forth, at once an origin and an initiation. Every return brings unexpected changes: "We must come back and back to the same place and find it subtly altered each time, like a traveler bewitched by lords of the fairy, until he is filled with a presence he would not otherwise have admitted." The poem's field is "where the disturbance is, where the words / awaken" (RB,51 ) unpredicted changes. It appears to hold a boundary "against chaos," yet "the sound of words waits-- / a barbarian host at the borderline of sense" (FD, 135). The poem is a "place of first permission" where a universe of words is given one of its voices. Poetic speech has the tension "of the ominous, for a world that would speak is itself a language of omens." So this meadow, giving illusory bounds to infinite speech, becomes an "everlasting omen of what is."

"What is," the governing ground of reality, is for Duncan essentially a reservoir of potential interchanges: "In a field of interacting melodies a single note may belong to both ascending and descending figures, and, yet again, to a sustaining chord or discord." The poem creates its own field within the larger field of words by establishing lines of force between specific harmonies and disharmonies. These "are rimes, Sounding in each other" and "the rimes or reoccurrences are knots in the web or tissue of reality." "That one image may recall another," Duncan writes, "finding depth in the resounding, is the secret of rime and measure. The time of a poem is felt as a recognition of return in vowel tone and in consonant formations, of pattern in the sequence of syllables, in stress and in pitch of a melody, of images and meanings." "Rime" for Duncan covers interactions among both sounds and images, as well as interactions between them.

In "Often I Am Permitted to Return to a Meadow," this net of sound and meaning keeps the meadow image coherent despite the associative digressions. The images of the Queen or Lady and the stanzas about the children's game would disrupt the poem if its verbal ground were not strong enough to support them. The poem's aural design is exactly sufficient, managing simultaneously to sustain and threaten. It includes the antiphonal phrasing of the second line and the first phrase of the third, the assonance of "made place," the consonance of "heart" and "thought" and later of "field folded," the visual rhyme of "near" and "heart," the repetition of "there" with "therein" in the fifth line, the internal rhyme of "all" and "hall" in the second stanza, echoed by "fall" in the third and "fall all" in the fourth. Throughout, there is considerable alliteration. Duncan does not establish a strict sound pattern but employs a variety of devices to make the aural field freely associative and unpredictable. Sound and meaning become mutually supportive, while seeming outside the poet's full control. Sound could, we fear, make the poetry nonsensical. Yet there is considerable attraction in the supreme and empty meaning lodged in the random architecture of sounds:

rhymes that mimic much of loss, ghost goings,

words lost in passing, echoed

where they fall, againnesses of sound only

This failure of sense is melody most

By Cary Nelson. From Our Last First Poets: Vision and History in Contemporary American Poetry. Copyright 1981 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois.

Norman M. Finklestein

Duncan's absorption with primal acts of language, acts which "take place" in a poetic terrain that is invoked by the poet's utterance but also maintains an independent metaphysical existence, leads him to The Opening of the Field. This volume, with its prophetic title, fluid open forms and magnificent lyricism, marks the beginning of Duncan's mature work, that continues with no interruption through Roots and Branches (1964) and Bending the Bow (1968). The Structure of Rime and Passages, the two series poems that wind their ways through these volumes and beyond, argue for the unification of Duncan's poetic efforts in ways unprecedented in his earlier work. Themes reappear continually in these books, providing a sense of unity that works against the boundaries of discrete poems. Adhering strictly to chronological order, Duncan allows his individual lyrics to punctuate the flow of the open forms. The result is a genuine tapestry, or more precisely, a world/book that serves as a vessel for the continual inclusion of myth, current events and enduring cultural and literary antecedents. This is Duncan's unique version of field poetics, in which the poem, as Michael Davidson notes, "does not imitate but enacts natural and cosmic orders: it does not seek to 'contain' meaning but to discover immanent meanings."

The lawfulness of this stance becomes apparent in the first poem of The Opening of the Field, the seminal post-Modern lyric "Often I Am Permitted To Return To A Meadow." Here, the idea of composition by field literally becomes the dominant metaphor for the discovery of creative freedom within the bounds of necessity:

as if it were a scene made-up by the mind,

that is not mine, but is a made place,that is mine, it is so near to the heart,

an eternal pasture folded in all thought

so that there is a hall thereinthat is a made place, created by light

wherefrom the shadows that are forms fall.

The meadow is of the poet, but is Other than the poet as well, and in such ambiguity resides the linguistic tension needed for the poem to resolve itself as completed utterance. Turning continually on the dichotomy of inner and outer worlds, the syntax rushes breathlessly forward, shaping the poem into the image of Duncan's ideal Form, which exists simultaneously in the mind, in the poem, in the exterior world and in a transcendental spiritual reality. The poem, the made place, is the manifestation of the creative will, Duncan's muse, "the Lady," "the First Beloved," who is also the Kabbalistic Shekinah, co-existing with God at the Creation. She inspires the poem even as she brings the poet his dream of children in a ring dancing in the wind-blown field, "the place of first permission," the scene of initiation into visionary experience. It is here that the poet is permitted to go each time inspiration comes to him, and it is this notion of freedom found in necessity that secures the poem’s lawfulness.

from "Robert Duncan, Poet of the Law." Sagetrieb Vol. 2 (1983), No. 1: 80-81.

Christopher Beach

Duncan sees in Pound's early writing on Imagism and on the troubadours the possibility of an almost Whitmanian aesthetic, but one that is too firmly entrenched in the past. Pound's thought "does not go forward with contemporary scientific imagination

to a poetic vision of the Life Process and the Universe but goes back to Ficino and the Renaissance ideas" (PC, 190). In Duncan's "opening" poem, "Often I Am Permitted to Return to a Meadow," he creates an ideogram that can include both of his predecessors and that has indications of both past and future.

It is only a dream of the grass blowing

east against the source of the sun

in an hour before the sun's going downwhose secret we see in a children's game

of ring a round of roses told.

The "dream" and the "secret" are words from the realm of mystery, a level of language Duncan feels Pound tries to exclude from his poetic world. These are words "pregnant" with meaning, and they bring "children" into the field of knowledge and experience that make up the poem and the book, this particular manifestation of future life is, like the female sexuality that produced it, absent from Pound's vision.

But the image works on two other levels as well: the "grass blowing / east against the source of the sun" is a metamorphosis of a Poundian ideogram, that of east as the sun caught in branches, and a powerful evocation of the Pound of the Pisan Cantos and after—"a man on whom the sun has gone down" (C, 430) .These same three lines also allude to Whitman, to the grass of Leaves of Grass blowing in the winds of time and to the "mysterious" and "prophetic" message of Democratic Vistas and that dream vision, "Song of Myself."

There is also a Duncanesque pun here: "the source of the sun" is also the source of the son, Whitman as father to Pound in the last "hour" of his life and subsequently Pound as the father to Duncan himself. Duncan is now a child seeking "permission " to enter his phase of "mature" poetry, ready to take responsibility for the field as "a given property of the mind / that certain bounds hold against chaos." "We see" (vision as phanopoeia and as apotheosis) the clear and defined image (though through a dream) as we experience the explicitly musical (melopoeic) properties of language in the nursery-rhyme line "of ring a round of roses told." We also encounter the logopoeia of a "dance of the mind" at the end of the poem, a dance that involves the juxtaposition of two central images. The last line of the poem, "everlasting omen of what is," reconciles past, present, and future, bringing together in the poetic process a childlike openness to new experience, the work of the present poet, and the inspiration provided by predecessors such as Whitman and Pound.

As Norman Finkelstein has observed, "Often I Am Permitted . . . " is a "seminal post-modern lyric"; it is an embodiment of the Poundian virtues of precision and workmanship but at the same time allows the freer play of "rhetoric" that is a legacy of Whitman and of the Romantic tradition. It is a poem intended to be read in the tradition of Whitman, Pound, and Williams as an "open" and "inclusive" work, less interested in its own autonomous "intramural" relations than in its multivalent relationship to sources in the natural world (spatial), in poetic models (temporal), and in the realm of an informing spiritual experience (eternal and virtually unbounded) that allows a larger field of poetry to be "folded" into the poem. The poem also serves more locally as an introduction to the poems that follow it in the book and, indeed, through the open-ended "Structure of Rime" sequence, to poems that are to come after the end of the book. Most of the poem's resonances are not apparent without a knowledge of the other poems in The Opening of the Field and, indeed, without some previous knowledge of Duncan's work and derivations.

Duncan's vision of the field, "meadow," or "pasture" as a communal place consisting of various interacting living communities, yet also open to the human community, establishes the poem and the book to follow in the choric tradition of Duncan's predecessors. It moves from the personal statement of the title to the shared vision of a secret "we see in a children's game." Like Duncan's poem, the secret can be appreciated only in the context of a larger community of concerns. Duncan's poetry in The Opening of the Field demonstrates the desire he shares with Pound and his other primary models to reach outside the concerns of a contained, isolated, solipsistic, or hermetic "lyric self" to the needs of a poetic or artistic community, to the needs of a "world community" of common ecological and spiritual concerns, and to the sense of community as nation exemplified by Whitman's Democratic Vistas and Pound's "American Cantos."

from ABC of Influence: Ezra Pound and the Remaking of American Poetic Tradition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992. Copyright © 1992 by the Regents of the University of California.

Donald K. Gutierrez

. . .at the core of this subject-object fusion or reversibility [in "Often I Am Permitted to Return to a Meadow"] is a visionary sense of an ideal enclave. . . .

In lines 2-6, the fluctuations between mind and place are so fleet and involuted that the traditional rationalist split between the two is broken down. Thus from this "derangement of the senses" we are prepared for the next turn, the metaphor of architecture. If a place can exist in the mind, it is not a large step to include buildings, built places, something more cultural than meadows or pastures, but like the latter a subdivision of place, though a place in the mind

The opening lines deserve a closer look. First, we are told that the meadow to which the poet or speaker is allowed to return is not a mentally constructed place, and thus is not his. Yet, the poem states next, the meadow is a "made place," and in this different sense does belong to the poet. So how can a place, Duncan's meadow, both be and not be part of the mind? The implication is that this sense of a special place, though not a constituent of the poet's personality or character, is part of a deeper, more impersonal, inheritance, something perhaps akin to a visitation from Jung's Collective Unconscious. Such an image would not be the poet's, yet, once experienced and assimilated, becomes his (and the reader's), because it is "so near to the heart."

This archetypal activity in the mind readily leads from pasture to hall, allowing "architectures" to extend their own figurative facets so as to include another basic and monistic feature of the poem, the archetypal female. Duncan refers in the fourth and fifth stanzas to three rather grand-sounding women, the First Beloved, the Lady, and a Queen Under the Hill. These are all prototypical ladies, suggestive of one's mother ("First Beloved"), the Virgin Mary (the "Lady"), and a primeval Earth Mother or pre-Christian Mediterranean matriarch as well as a dead female personage. A key monistic transference in the poem, then, is that "architectures," part of the structure of those beautiful places from which, with the polished ease of a pleasant dream, one situation or context merges into and becomes another, have become archetypal women with broad cultural associations (Mother, Christianity, Graeco-Roman and Mediterranean myth). This transference is not surprising. Woman is traditionally associated with most Beautiful Places; in more than just romantic contexts she is often even the heart and center of them.

Thus we have three changes that can be varyingly stated: place--mind--architecture--women, or, mind--place--architecture--women. I have already alluded to the philosophical and esthetic implications of whether mind or place should come first (or either), a consideration I will try to resolve later. Let us instead consider the fact that another mirror or word follows these four key terms and figures: "words." The words in a rudimentary sense are the foundation of the poem; without them, none of the other basic contexts or shifting images would exist. This is obvious, as is the fact that this symbolic treatment of words represents a poet's tribute to the chief medium of his art. But it is also implied that the shifting imagery, the Cocteauesque montage, had its life, its ultimate being, in words. Does this mean then that words, language, constitute the essence of the poem? Were this so, the subtlety of the poem would be limited. On the contrary, the poem seems to me to transcend this delimiting homage by making even words subordinate not merely to place again, but to a special place: le beau lieu. All this and more is crystallized in stanza five, which I read as the climax of the poem:

She it is Queen Under the Hill

whose hosts are a disturbance of words within words

that is a folded field

I feel that the stanza represents a climax because the five key terms of the poem are either mentioned or implied, and are mentioned in a manner that gives them the form of final meaning, like figures in a frieze. As Queen Under the Hill, the dead (but also living) Goddess, one's Mother (who lives in one's mind), whether dead or living, or mortal or immortal female force, this "Triple Goddess" harbors hosts. A richly connotative word, "hosts" refers us back to the "hall" and "architecture" that grew out of the pastoral of the mind. It also suggests in this context that words are hosts to readers as guests, and that thus we too, through poetry's words, have access to the "eternal pasture that is so near the heart." But "hosts" also suggest a large number or multitude, and if one recalls the earlier etymology of the word "guest," the latent meaning of a guest being a captive to one's host means here also that one is a captive to this primal woman, as a poet is captive to the creative imperatives of the Muse. And the reader is also a "guest" to these associations as they may apply; more directly, he is captive to the "disturbance of words, within words," and to their ultimate and transcendent conversion into the "field folded," that is, the Beautiful Place. Thus the reader, through the poet, the artist, is captive in the ideal enclave made by the subject-object fusing of the poet's visionary exaltation.

What, however, is to be made of stanzas 7 and 8, which appear to belittle the preceding rhapsody of vision? "It is only a dream we are told, a dream

Of the grass blowing

east against the source of the sun

in an hour before the sun's going down. . .

"Dream" here at first seems negative in its diminishment of visionary experience; the whole event is reduced to an image of natural energy, wind moving against grass towards the center and symbol of prime energy. This directional source of energy, the East, contains a secret when connected with the lines "whose secret we see in a children's game/ of ring a round of roses told."

. . .

The "secret" of the source of the sun told in this game is death, but it is also "magic" protection against death in the form of the creative flow of nature that represents absolute beauty, and, by association, art. The source of the sun, the East, is a symbol of birth, rebirth, and new life, the very opposite of the West with its traditional associations of death. Like a child, the artist, the poet, knows the secret of the sun, of sources of energy. The "secret" is that what is generated by energy also perishes. But the remaining part of this secret is that energy is eternal, and that if the sun goes down, it also comes up again. Energy is Eternal Delight, said Blake. Energy, implies Duncan, is recurrent light, and recurrent inspiration. Thus, the dream encompasses Duncan's meadow vision rather than negating it; it enriches the meaning of his visionary meadow by providing a fundamental source to the Beautiful Place.

That these two stanzas do not basically undercut the poem is further suggested by the affirmative character of the final stanzas of the poem. . . .

Duncan makes the connection between meadow and mind in terms of a simile, thus suggesting a certain poignancy in the gap created by the subject-object (or subject-subject) differentiation. Whether or not that separation is essential, too much distance between mind and meadow would make life excessively abstract, bleak, and cold. If, on the other hand, meadow and mind were one, and in some senses they perhaps can be, such an identification would last only briefly, analogous as it otherwise could be to several straight hours of joy or terror. The union of meadow and mind is best temporary. It makes return, and thus regeneration, possible, and perhaps is all of the Beau Lieu needed to retain these "bounds" against chaos. And a Beautiful Place would lose its beauty if experienced too much.

The "place of first permission: is, then, a visionary haunt, a special place. What permits this return, this special, archetypal visitation? Clearly it is the mind itself as self-creation; it is the mind in its first realization of its creative, artistic character, a kind of height and self consciousness. Permission to this type of person is self-endowed. In this sense, the artist, to vary Wordsworth, is father of the artistic man. Beyond this oblique signal of artistic autonomy, we have a gesture of the supreme reality of the artistic imagination. This mind-place, haunt of creative sources and fertility, is also the "omen" of not only what is important, but of what will be important in the future.

Thus Duncan's poem is a celebration of the powers of art and artist through a symbolic presentation of the preserves of art, the special "meadows" and agents of inspiration which evokes the "architectures," Lawrentian flaming flowers, and interfolded pastures and thought basic at least to a certain kind of poetry. The first five lines of the poem (including the title) imply the resolution of the mind-and-surroundings problem concerning whether the beautiful place is "out there" or internal: surely, it's both. The scene is not originally the poet's, but he makes it his through imaginational re-shaping ( a "folded field"), and also by "placing" it near his "heart," by giving it, that is, emotional force and substance. Once this internal consolidation of the external occurs, the "real" location of the meadow becomes insignificant. The significant thing--the highest reality, the "everlasting omen"--is what the poetic mind makes of its creative sources, and that regeneration occurs, for poet, for all.

from Donald K. Gutierrez, "The Beautiful Place in the Mind: Robert Duncan's "Often I Am Permitted to Return to a Meadow." American Poetry (Fall 1988). Reprinted in Breaking through to the Other Side : Essays on

Realization in Modern Literature by Donald Gutierrez. Troy, N.Y. : Whitson Pub. Co., 1994. Copyright © Donald K. Gutierrez.

Return to Robert Duncan