On The Waste Land

Cleanth Brooks

The bundle of quotations with which the poem ends has a very definite relation to the general theme of the poem and to several of the major symbols used in the poem. Before Arnaut leaps back into the refining fire of Purgatory with joy he says: "I am Arnaut who weep and go singing; contrite I see my past folly, and joyful I see before me the day I hope for. Now I pray you by that virtue which guides you to the summit of the stair, at times be mindful of my pain." This theme is carried forward by the quotation from Pervigilium Veneris: "When shall I be like the swallow." The allusion is also connected with the Philomela symbol. (Eliot's note on the passage indicates this clearly.) The sister of Philomela was changed into a swallow as Philomela was changed into a nightingale. The protagonist is asking therefore when shall the spring, the time of love, return, but also when will he be reborn out of his sufferings, and--with the special meaning which the symbol takes on from the preceding Dante quotation and from the earlier contexts already discussed--he is asking what is asked at the end of one of the minor poems: "When will Time flow away."

The quotation from "El Desdichado," as Edmund Wilson has pointed out, indicates that the protagonist of the poem has been disinherited, robbed of his tradition. The ruined tower is perhaps also the Perilous Chapel, "only the wind's home," and it is also the whole tradition in decay. The protagonist resolves to claim his tradition and rehabilitate it.

The quotation from The Spanish Tragedy--"Why then Ile fit you. Hieronymo's mad againe"--is perhaps the most puzzling of all these quotations. It means, I believe, this: The protagonist's acceptance of what is in reality the deepest truth will seem to the present world mere madness. ("And still she cried . . . 'Jug jug' to dirty ears.") Hieronymo in the play, like Hamlet, was "mad" for a purpose. The protagonist is conscious of the interpretation which will be placed on the words which follow--words which will seem to many apparently meaningless babble, but which contain the oldest and most permanent truth of the race:

Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata.

Quotation of the whole context from which the line is taken confirms this interpretation. Hieronymo, asked to write a play for the court's entertainment, replies:

Why then, I'll fit you; say no more.

When I was young, I gave my mind

And plied myself to fruitless poetry;

Which though it profit the professor naught

Yet it is passing pleasing to the world.

He sees that the play will give him the opportunity he has been seeking to avenge his son's murder. Like Hieronymo, the protagonist in the poem has found his theme; what he is about to perform is not "fruitless."

After this repetition of what the thunder said comes the benediction:

Shantih Shantih Shantih

The foregoing account of The Waste Land is, of course, not to be substituted for the poem itself. Moreover, it certainly is not to be considered as representing the method by which the poem was composed. Much which the prose expositor must represent as though it had been consciously contrived obviously was arrived at unconsciously and concretely.

The account given above is a statement merely of the "prose meaning," and bears the same relation to the poem as does the "prose meaning" of any other poem. But one need not perhaps apologize for setting forth such a statement explicitly, for The Waste Land has been almost consistently misinterpreted since its first publication. Even a critic so acute as Edmund Wilson has seen the poem as essentially a statement of despair and disillusionment, and his account sums up the stock interpretation of the poem. Indeed, the phrase, "the poetry of drouth," has become a cliché of left-wing criticism. It is such a misrepresentation of The Waste Land as this which allows Eda Lou Walton to entitle an essay on contemporary poetry, "Death in the Desert"; or which causes Waldo Frank to misconceive of Eliot's whole position and personality. But more than the meaning of one poem is at stake. If The Waste Land is not a world-weary cry of despair or a sighing after the vanished glories of the past, then not only the popular interpretation of the poem will have to be altered but also the general interpretations of post-War poetry which begin with such a misinterpretation as a premise.

Such misinterpretations involve also misconceptions of Ellot's technique. Eliot's basic method may be said to have passed relatively unnoticed. The popular view of the method used in The Waste Land may be described as follows: Eliot makes use of ironic contrasts between the glorious past and the sordid present--the crashing irony of

But at my back from time to time I hear

The sound of horns and motors, which shall bring

Sweeney to Mrs. Porter in the spring.

But this is to take the irony of the poem at the most superficial level, and to neglect the other dimensions in which it operates. And it is to neglect what are essentially more important aspects of his method. Moreover, it is to overemphasize the difference between the method employed by Eliot in this poem and that employed by him in later poems.

The basic method used in The Waste Land may be described as the application of the principle of complexity. The poet works in terms of surface parallelisms which in reality make ironical contrasts, and in terms of surface contrasts which in reality constitute parallelisms. (The second group sets up effects which may be described as the obverse of irony.) The two aspects taken together give the effect of chaotic experience ordered into a new whole, though the realistic surface of experience is faithfully retained. The complexity of the experience is not violated by the apparent forcing upon it of a predetermined scheme.

The fortune-telling of "The Burial of the Dead" will illustrate the general method very satisfactorily. On the surface of the poem the poet reproduces the patter of the charlatan, Madame Sosostris, and there is the surface irony: the contrast between the original use of the Tarot cards and the use made by Madame Sosostris. But each of the details (justified realistically in the palaver of the fortune-teller) assumes a new meaning in the general context of the poem. There is then, in addition to the surface irony, something of a Sophoclean irony too, and the "fortune-telling," which is taken ironically by a twentieth-century audience, becomes true as the poem develops--true in a sense in which Madame Sosostris herself does not think it true. The surface irony is thus reversed and becomes an irony on a deeper level. The items of her speech have only one reference in terms of the context of her speech: the "man with three staves," the "one-eyed merchant," the "crowds of people, walking round in a ring," etc. But transferred to other contexts they become loaded with special meanings. To sum up, all the central symbols of the poem head up here; but here, in the only section in which they are explicitly bound together, the binding is slight and accidental. The deeper lines of association only emerge in terms of the total context as the poem develops--and this is, of course, exactly the effect which the poet intends.

[. . . .]

The poem would undoubtedly be "clearer" if every symbol had a single, unequivocal meaning; but the poem would be thinner, and less honest. For the poet has not been content to develop a didactic allegory in which the symbols are two-dimensional items adding up directly to the sum of the general scheme. They represent dramatized instances of the theme, embodying in their own nature the fundamental paradox of the theme.

We shall better understand why the form of the poem is right and inevitable if we compare Eliot's theme to Dante's and to Spenser's. Eliot's theme is not the statement of a faith held and agreed upon (Dante's Divine Comedy) nor is it the projection of a "new" system of beliefs (Spenser's Faerie Queene). Eliot's theme is the rehabilitation of a system of beliefs, known but now discredited. Dante did not have to "prove" his statement; he could assume it and move within it about a poet's business. Eliot does not care, like Spenser, to force the didacticism. He prefers to stick to the poet's business. But, unlike Dante, he cannot assume acceptance of the statement. A direct approach is calculated to elicit powerful "stock responses" which will prevent the poem's being read at all. Consequently, the only method is to work by indirection. The Christian material is at the center, but the poet never deals with it directly. The theme of resurrection is made on the surface in terms of the fertility rites; the words which the thunder speaks are Sanscrit words.

We have been speaking as if the poet were a strategist trying to win acceptance from a hostile audience. But of course this is true only in a sense. The poet himself is audience as well as speaker; we state the problem more exactly if we state it in terms of the poet's integrity rather than in terms of his strategy. He is so much a man of his own age that he can indicate his attitude toward the Christian tradition without falsity only in terms of the difficulties of a rehabilitation; and he is so much a poet and so little a propagandist that he can be sincere only as he presents his theme concretely and dramatically.

To put the matter in still other terms: the Christian terminology is for the poet a mass of clichés. However "true" he may feel the terms to be, he is still sensitive to the fact that they operate superficially as clichés, and his method of necessity must be a process of bringing them to life again. The method adopted in The Waste Land is thus violent and radical, but thoroughly necessary. For the renewing and vitalizing of symbols which have been crusted over with a distorting familiarity demands the type of organization which we have already commented on in discussing particular passages: the statement of surface similarities which are ironically revealed to be dissimilarities, and the association of apparently obvious dissimilarities which culminates in a later realization that the dissimilarities are only superficial--that the chains of likeness are in reality fundamental. In this way the statement of beliefs emerges through confusion and cynicism--not in spite of them.

From Modern Poetry and the Tradition. Copyright © 1939 by the University of North Carolina Press.

Joseph Frank

In the Cantos and The Waste Land, however, it should have been clear that a radical transformation was taking place in aesthetic structure; but this transformation has been touched on only peripherally by modern critics. R. P. Blackmur comes closest to the central problem while analyzing what he calls Pound's "anecdotal" method. The special form of the Cantos, Blackmur explains, "is that of the anecdote begun in one place, taken up in one or more other places, and finished, if at all, in still another. This deliberate disconnectedness, this art of a thing continually alluding to itself, continually breaking off short, is the method by which the Cantos tie themselves together. So soon as the reader's mind is concerted with the material of the poem, Mr. Pound deliberately disconcerts it, either by introducing fresh and disjunct material or by reverting to old and, apparently, equally disjunct material."

Blackmur's remarks apply equally well to The Waste Land, where syntactical sequence is given up for a structure depending on the perception of relationships between disconnected word-groups. To be properly understood, these word-groups must be juxtaposed with one another and perceived simultaneously. Only when this is done can they be adequately grasped; for, while they follow one another in time, their meaning does not depend on this temporal relationship. The one difficulty of these poems, which no amount of textual exegesis can wholly overcome, is the internal conflict between the time-logic of language and the space-logic implicit in the modern conception of the nature of poetry.

Aesthetic form in modern poetry, then, is based on a space-logic that demands a complete reorientation in the reader's attitude toward language. Since the primary reference of any word-group is to something inside the poem itself, language in modern poetry is really reflexive. The meaning-relationship is completed only by the simultaneous perception in space of word-groups that have no comprehensible relation to each other when read consecutively in time. Instead of the instinctive and immediate reference of words and word-groups to the objects or events they symbolize and the construction of meaning from the sequence of these references, modern poetry asks its readers to suspend the process of individual reference temporarily until the entire pattern of internal references can be apprehended as a unity.

It would not be difficult to trace this conception of poetic form back to Mallarmé’s ambition to create a language of "absence" rather than of presence—a language in which words negated their objects instead of designating them; nor should one overlook the evident formal analogies between The Waste Land and the Cantos and Mallarmé’s Un Coup de dés. Mallarmé, indeed, dislocated the temporality of language far more radically than either Eliot or Pound has ever done; and his experience with Un Coup de dés showed that this ambition of modern poetry has a necessary limit. If pursued with Mallarmé’s relentlessness, it culminates in the self-negation of language and the creation of a hybrid pictographic "poem" that can only be considered a fascinating historical curiosity. Nonetheless, this conception of aesthetic form, which may be formulated as the principle of reflexive reference, has left its traces on all of modem poetry. And the principle of reflexive reference is the link connecting the aesthetic development of modern poetry with similar experiments in the modern novel.

From The Idea of Spatial Form. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Grover Smith

The Waste Land summarizes the Grail legend, not precisely in the usual order, but retaining the principal incidents and adapting them to a modern setting. Eliot's indebtedness both to Sir James Frazer and to Jessie L. Weston's From Ritual to Romance (in which book he failed to cut pages 138-39 and 142-43 of his copy) is acknowledged in his notes. Jessie L. Weston's thesis is that the Grail legend was the surviving record of an initiation ritual. Later writers have reaffirmed the psychological validity of the link between such ritual, phallic religion, and the spiritual content of the Greek Mysteries. Identification of the Grail story with the common myth of the hero assailing a devil-dragon underground or in the depths of the sea completes the unifying idea behind The Waste Land. The Grail legend corresponds to the great hero epics, it dramatizes initiation into maturity, and it bespeaks a quest for sexual, cultural, and spiritual healing. Through all these attributed functions, it influenced Eliot's symbolism.

Parallels with yet other myths and with literary treatments of the "quest" theme reinforce Eliot's pattern of death and rebirth. Though The Tempest, one of Eliot's minor sources, scarcely depicts an initiation "mystery," Colin Still, in a book of which Eliot has since written favorably (Shakespeare's Mystery Play), had already advanced the theory in 1921 that it implies such a subject." And Tiresias is not simply the Grail knight and the Fisher King but Ferdinand and Prospero, as well as Tristan and Mark, Siegfried and Wotan. In his feminine role he is not simply the Grail-maiden and the wise Kundry but the sibyl, Dido, Miranda, Brünnhilde. Each of these represents one of the three main characters in the Grail legend and in the mystery cults--the wounded god, the sage woman (transformed in some versions of the Grail legend into a beautiful maiden), and the resurrected god, successful quester, or initiate. Counterparts to them figure elsewhere; Eliot must have been conscious that the "Ancient Mariner" and "Childe Roland" had analogues to his own symbolism.

In adopting fertility symbolism, Eliot was probably influenced by Stravinsky's ballet Le Sacre du printemps. The summer before writing The Waste Land he saw the London production, and on reviewing it in September he criticized the disparity between Massine's choreography and the music. He might almost have been sketching his own plans for a work applying a primitive idea to contemporary life:

In art there should be interpenetration and metamorphosis. Even the Golden Bough can be read in two ways: as a collection of entertaining myths, or as a revelation of that vanished mind of which our mind is a continuation. In everything in the Sacre du Printemps, except in the music, one missed the sense of the present. Whether Stravinsky's music be permanent or ephemeral I do not know; but it did seem to transform the rhythm of the steppes into the scream of the motor horn, the rattle of machinery, the grind of wheels, the beating of iron and steel, the roar of the underground railway, and the other barbaric cries of modern life; and to transform these despairing noises into music.

In The Waste Land he imposed the fertility myth upon the world about him.

Eliot's waste land suffers from a dearth of love and faith. It is impossible to demarcate precisely at every point between the physical and the spiritual symbolism of the poem; as in "Gerontion" the speaker associates the failure of love with his spiritual dejection. It is clear enough, however, that the contemporary waste land is not, like that of the romances, a realm of sexless sterility. The argument emerges that in a world that makes too much of the physical and too little of the spiritual relations between the sexes, Tiresias, for whom love and sex must form a unity, has been ruined by his inability to unify them. The action of the poem, as Tiresias recounts it, turns thus on two crucial incidents: the garden scene in Part I and the approach to the Chapel Perilous in Part V. The one is the traditional initiation in the presence of the Grail; the other is the mystical initiation, as described by Jessie L. Weston, into spiritual knowledge. The first, if successful, would constitute rebirth through love and sex; the second, rebirth without either. Since both fail, the quest fails, and the poem ends with a formula for purgatorial suffering, through which Tiresias may achieve the second alternative after patience and self-denial--perhaps after physical death. The counsel to give, sympathize, and control befits one whom direct ways to beatitude cannot release from suffering.

From T.S. Eliot’s Poetry and Plays: A Study in Sources and Meaning. Copyright © 1956 by The University of Chicago Press.

Stephen Spender

Conrad's Heart of Darkness is of course one of the "influences" in TheWaste Land. It seems to me, though, much more than this. Conrad's story is of the primitive world of cannibalism and dark magic penetrated by the materialist, supposedly civilized world of exploitation and gain; and of the corruption of the mind of a man of civilized consciousness by the knowledge of the evil of the primitive (or the primitive which becomes evil through the unholy union of European trade and Congolese barbarism). The country of them as described by Conrid is a country of pure horror. Eliot is usually thought of as a sophisticated writer, an "intellectual." For this reason, the felling of primitive horror which rises from depths of his poetry is overlooked. Yet it is there in the rhythms, often crystallizing in some phrase which suggests the drums beating through the jungle darkness, the scuttling, clawing, shadowy forms of life in the depths of the sea, the spears of savages shaking across the immense width of the river, the rough-hewn images of prehistoric sculptures found in the depths of the primeval forest, the huge cactus forms in deserts, the whispering of ghosts at the edge of darkness. Probably this is the most Southern (in the American sense) characteristic of Eliot, reminding one that he was a compatriot of Edgar Allan Poe and William Faulkner. And Conrad's Heart of Darkness is a landscape with which Eliot is deeply, disquietedly, guiltily almost, familiar, and with which he contrasts effects of sunlight, lips trembling in prayer, eyes gazing into the heart of light or hauntingly into the eyes, a ship answering to the hand on a tiller as a symbol of achieved love and civilization.

From T.S. Eliot (New York: Viking Press, 1975): 120-21.

Eloise Knapp Hay

The Waste Land, Eliot's first long philosophical poem, can now be read simply as it was written, as a poem of radical doubt and negation, urging that every human desire be stilled except the desire for self-surrender, for restraint, and for peace. Compared with the longing expressed in later poems for the "eyes" and the "birth," the "coming" and "the Lady" (in "The Hollow Men," the Ariel poems, and "Ash-Wednesday"), the hope held out in The Waste Land is a negative one. Following Hugh Kenner's recommendation, we should lay to rest the persistent error of reading The Waste Land as a poem in which five motifs predominate: the nightmare journey, the Chapel, the Quester, the Grail Legend, and the Fisher King. The motifs are indeed introduced, as Eliot's preliminary note to his text informs us, but if (as this note says) "the plan and a good deal of the incidental symbolism of the poem were suggested by Miss Jessie L. Weston's book on the Grail legend," the plan can only have been to question, and even to propose a life without hope for, a quest, or Chapel, or Grail in the modern waste land. The themes of interior prison and nightmare city--or the "urban apocalypse" elucidated by Kenner and Eleanor Cook--make much better sense when seen as furnishing the centripetal "plan" and "symbolism," especially when one follows Cook's discussion of the disintegration of all European cities after the First World War and the poem's culminating vision of a new Carthaginian collapse, imagined from the vantage point of India's holy men. A passage canceled in the manuscript momentarily suggested that the ideal city, forever unrealizable on earth, might be found (as Plato thought) "in another world," but the reference was purely sardonic. Nowhere in the poem can one find convincing allusions to any existence in another world, much less to St. Augustine's vision of interpenetration between the City of God and the City of Man in this world. How, then, can one take seriously attempts to find in the poem any such quest for eternal life as the Grail legend would have to provide if it were a continuous motif--even a sardonic one?

It seems that only since Eliot's death is it possible to read his life forward--understanding The Waste Land as it was written, without being deflected by our knowledge of the writer's later years. Before Eliot's death the tendency was to read the poem proleptically--as if reflecting the poems of the later period. This is how Cleanth Brooks, writing the first fully elucidative essay on The Waste Land, read it, stressing the Grail legends, the longing for new life, rather than the purely negative aspects of the theme. Thus Brooks interpreted the Sibyl's appeal for death at the beginning of the poem as exactly parallel to the Magus's appetite for death in the Ariel poems (the Magus's, of course, filled with the pain of knowing that Christ had subjected himself to weak mortality and not knowing yet the Resurrection). To make the Sibyl and the Magus parallel was to read Eliot's development backward--perhaps an irresistible temptation when the pattern in his life was so little known and when (as then in 1939) Brooks was acquainted with the man at work on Four Quartets, who had recently produced the celebrated Murder in the Cathedral. It was also irresistible, in a culture still nominally Christian, to hope that The Waste Land was about a world in which God was not dead. But the poem was not about such a world.

Within ten years after finishing The Waste Land, Eliot recognized that the poem had made him into the leader of a new "way." His own words of 1931, however, require us to read the poem as having pushed this roadway through to its end--for him. It was no Grail quest. Those who followed him into it, and stayed on it, he said in "Thoughts After Lambeth," "are now pious pilgrims, cheerfully plodding the road from nowhere to nowhere." There could be no more decisive reference to the negative way he had followed till 1922, and also to the impasse where it ended.

A good reading of The Waste Land must begin, then, with recognition that while it expressed Eliot's own "way" at the time, it was not intended to lay down a way for others to follow. He did not expect that his prisonhouse would have corridors connecting with everyone else's. "I dislike the word 'generation' [he said in "Thoughts After Lambeth"), which has been a talisman for the last ten years; when I wrote a poem called The Waste Land some of the more approving critics said that I had expressed the 'disillusionment of a generation,' which is nonsense. I may have expressed for them their own illusion of being disillusioned, but that did not form part of my intention." Dismay at finding his personal, interior journey (which he later called "rhythmic grumbling") converted into a superhighway seems to have been one of the main impulses toward his discovery of a new way after 1922.

If we listen attentively to the negations of The Waste Land, they tell us much about the poem that was missed when it was read from the affirmative point of view brought to it by its early defenders and admirers. Ironically, it was only its detractors--among them Eliot's friend Conrad Aiken--who acknowledged its deliberate vacuity and incoherence and the life-questioning theme of this first venture into "philosophical" poetry on Eliot's part. Aiken considered its incoherence a virtue because its subject was incoherence, but this was cool comfort either to himself or to Eliot, who was outraged by Aiken's opinion that the poem was "melancholy." It was far from being a sad poem--like the nineteenth-century poems that Eliot had criticized precisely because of their wan melancholias, based as he said on their excesses of desire over the possibilities that life can afford. Neither Aiken, who found the poem disappointing, nor I. A. Richards, who was exhilarated by its rejection of all "belief, " spotted the poem's focus on negation as a philosophically meditated position.

From T.S. Eliot’s Negative Way. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1982.

Michael H. Levenson

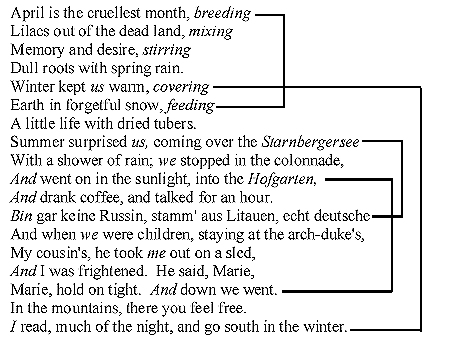

[Levenson quotes the opening four lines]

Who speaks these lines? – presumably whoever speaks these next lines:

[. . . .]

since the subject-matter (the life of the seasons) persists, as does the distinctive syntactic pattern (the series of present participles) and the almost obsessive noun-adjective pairings ("dead land," "spring rain," "little life," "dried tubers"). The second sentence, of course, introduces a new element, a narrating personal consciousness. But surely this need not signal a new speaker; it suggests rather that there is and has been a speaker, the unspecified "us," who will receive greater specification in the next several lines.

[. . . .]

Certainly we want to identify the "us" that winter kept warm with the "us" that summer surprised, and with the "we" who stop, go on, drink coffee and talk. That is how we expect pronouns to behave: same referents unless new antecedents. But if the pronouns suggest a stable identity for the speaker, much else has already become unstable. Landscape has given way to cityscape. General speculation (April as the "cruellest month") resolves into a particular memory: the day in the Hofgarten. And the stylistic pattern shifts. The series of participles disappears, replaced by a series of verbs in conjunction: "And went ... And drank ... And talked." The adjective-noun pattern is broken.

What can we conclude so far? -- that a strain exists between the presumed identity of the poem's speaker and the instability of the speaker's world. If this is the speech of one person, it has the range of many personalities and many voices -- a point that will gain clarity if we consider the remaining lines of the sequence:

[. . . .]

The line of German aggravates the strain, challenging the fragile continuity that has been established. Here is a new voice with a new subject-matter, speaking in another language, resisting assimilation. Is the line spoken, overheard, remembered? Among the poem's readers no consensus has emerged. Nor is consensus to be expected. In the absence of contextual clues, and Eliot suppresses such clues, the line exists as a stark, unassimilable poetic datum.

And yet, after that line a certain continuity is restored. The first-person plural returns; the pattern of conjunction reappears: "And when . . . And I . . . And down." Even that startling line of German, let us notice, had been anticipated in the "Hofgarten" and "Starnbergersee" of the previous lines. Discontinuity, in other words, is no more firmly established than continuity. The opening lines of the poem offer an elaborate system of similarities and oppositions, which might be represented in the following manner:

The diagram should indicate the difficulty. Lines 1-6 are linked by the use of present participles, lines 5-18 by personal pronouns, lines 8-12 by the use of German, lines 10-16 by the reiteration of the conjunction "and." The consequence is that in any given line we may find a stylistic feature which will bind it to a subsequent or previous line, in this way suggesting a continuous speaker, or at least making such a speaker plausible. But we have no single common feature connecting all the lines: one principle of continuity gives way to the next. And these overlapping principles of similarity undermine the attempt to draw boundaries around distinct speaking subjects. The poetic voice is changing; that we all hear. Certainly we hear it when we compare one of the opening lines to those at the end of the passage. But the changes are incremental, frustrating the attempt to make strict demarcations. How many speak in these opening lines? "One," "two" and "three" have been answers, but my point is that any attempt to resolve that issue provokes a collision of interpretive conventions. On the one hand, the sequence of first-person pronouns -- an "us " that becomes a "we," a "me" an "I," and then "Marie" -- would encourage us to read these lines as marking the steady emergence of an individual human subject. But if the march of pronouns would imply that Marie has been the speaker throughout, that suggestion is threatened in the several ways we have considered: the shift from general reflection to personal reminiscence, from landscape to cityscape, from participial connectives to conjunctions, the disappearance of the noun-adjective pattern, the use of German. Attitudes, moreover, have undergone a delicate, though steady, evolution. Can the person who was "kept . . . warm . . . in forgetful snow . . . " be that Marie, who prefers to "go south in winter?" Can the voice which solemnly intones the opening and explosive paradox: April is cruel, utter such conversational banalities as: "In the mountains, there you feel free"?

Perhaps -- but if we insist on Marie as the consistent speaker, if we ask her to lay hold of this complexity, we can expect only an unsteady grasp. The heterogeneity of attitude, the variety of tone, do not resolve into the attitudes and tones of an individual personality. In short, the boundaries of the self begin to waver: if we can no longer trust our pronouns, what can we trust? Furthermore, though we find it difficult to posit one speaker, it is scarcely easier to posit many, since we can say with no certainty where one concludes and another begins. Though the poem's opening lines do not hang together, neither do they fall cleanly apart. Here, as elsewhere, the poem plays between bridges and chasms, repetitions and aggressive novelties, echoes and new voices.

In the opening movement of The Waste Land, the individual subject possesses none of the formal dominance it once enjoyed in Conrad and James. No single consciousness presides; no single voice dominates. A character appears, looming suddenly into prominence, breaks into speech, and then recedes, having bestowed momentary conscious perception on the fragmentary scene. Marie will provide neither coherence nor continuity for the poem: having been named, she will disappear; her part is brief. Our part is larger, for the question we now face is the problem of boundaries in The Waste Land.

[. . . .]

Eliot, as we have already seen, rejects the need for any such integrating Absolute as a way of guaranteeing order. His theory of points of view means to obviate that need. Points of view, though distinct, can be combined. Order can emerge from beneath; it need not descend from above. And thus in the Monist he says of Leibniz' theory of the dominant monad: "I contend that if one recognizes two points of view which are quite irreconcilable and yet melt into each other, this theory is quite superfluous." And in the dissertation he writes that "the pre-established harmony is unnecessary if we recognize that the monads are not wholly distinct."

My italics are tendentious, dramatizing the repetitions in phrase. But the repetition is more than a chance echo; it identifies a problem which both the philosophy and the poetry address. How can one finite experience be related to any other? Put otherwise, how can difference be compatible with unity? Moreover, the poetic solution is continuous with the philosophic solution: individual experiences, individual personalities are not impenetrable. They are distinct, but not wholly so. Like the points of view described in the dissertation, the fragments in The Waste Land merge with one another, pass into one another.

Madame Sosostris, for instance, identifies the protagonist with the drowned sailor ("Here, said she/Is your card, the drowned Phoenician Sailor"). But the sailor, Phlebas, is also identified with Mr Eugenides: recall Eliot's phrase, "the one-eyed merchant, seller of currants, melts into the Phoenician Sailor." But, as Langbaum has shown, if the protagonist is identified with Phlebas and Phlebas with Eugenides, then it is difficult to escape the conclusion that the protagonist and the Smyrna merchant are, themselves, "not wholly distinct." What, then, do we make of these lines?

[Levenson quotes lines from "Under the brown fog of a winter noon" to "Followed by a weekend at the Metropole."

The protagonist, as Langbaum points out, "stands on both sides of the proposition," and such a conclusion will unnerve us only if we hold fast to traditional concepts of self, personal identity, personal continuity and the barriers between selves.

But in The Waste Land no consistent identity persists; the "shifting references" alter our notions of the self. The characters are little more than aspects of selves or, in the jargon of Eliot's dissertation, "finite centres," "points of view."

Here are the concluding lines of "The Fire Sermon":

[. . . .]

Lines from Augustine alternate with lines from the Buddha, and, as Eliot tells us in the footnote: "the collocation of these two representatives of eastern and western asceticism, as the culmination of this part of the poem, is not an accident." Of course it is not. It is the way the poem works: it collocates in order to culminate. It offers us fragments of consciousness, "various presentations to various viewpoints," which overlap, interlock, "melting into" one another to form emergent wholes. The poems is not, as it is common to say, built upon the juxtaposition of fragments: it is built out of their interpenetration. Fragments of the Buddha and Augustine combine to make a new literary reality which is neither the Buddha nor Augustine but which includes them both.

But at my back from time to time I hear

The sound of horns and motors, which shall bring

Sweeney to Mrs. Porter in the spring.

The echo from Marvell passes into an echo from Day: the poetic effect depends on amalgamating these distinct sources, on recognizing them as not wholly distinct. For we know, argues Eliot, "that we are able to pass from one point of view to another, that we are compelled to do so, and that the different aspects more or less hang together." The movement of The Waste Land is just such a movement among points of view: Marvell and Day, the Buddha and St Augustine, Ovid and Virgil.

We find ourselves in a position to confront a problem, which, though distant, is not forgotten: the problem of the poem's unity, or what comes to the same thing, the problem of Tiresias. We may begin to see how Tiresias can serve the function of "uniting all the rest," without that obliging us to conclude that all speech and all consciousness are the speech and consciousness of Tiresias. For, if we rush too quickly to Tiresias as a presiding consciousness, along the lines established by Conrad or James, then we lose what the text clearly asks us to retain: the plurality of voices that sound in no easy harmony. What Eliot says of the Absolute can be said of Tiresias, who, also, "dissolves at a touch into ... constituents." But this does not leave us with a heap of broken fragments; we have seen how the fragments are constructed into new wholes. If Tiresias dissolves into constituents, let us remember the moments when those constituents resolve into Tiresias. Tiresias is, in this sense, an intermittent phenomenon in the poem, a subsequent phenomenon, emerging out of other characters, other aspects. The two sexes may, as Eliot suggests, meet in Tiresias, but they do not begin there.

"The life of a soul," writes Eliot in the dissertation, "does not consist in the contemplation of one consistent world but in the painful task of unifying (to a greater and less extent) jarring and incompatible ones, and passing, when possible, from two or more discordant viewpoints to a higher which shall somehow include and transmute them." Tiresias functions in the poem in just this way: not as a consistent harmonizing consciousness but as the struggled-for emergence of a more encompassing point of view. The world, Eliot argues, only sporadically accessible to the knowing mind; it is a "felt whole in which there are moments of knowledge." And so, indeed, is The Waste Land such a felt whole with moments of knowledge. Tiresias provides not permanent wisdom but instants of lucidity during which the poem's angle of vision is temporarily raised, the expanse of knowledge temporarily widened.

The poem concludes with a rapid series of allusive literary fragments: seven of the last eight lines are quotations. But in the midst of these quotations is a line to which we must attach great importance: "These fragments I have shored against my ruins." In the space of that line the poem becomes conscious of itself. What had been a series of fragments of consciousness has become a consciousness of fragmentation: that may not be salvation, but it is a difference, for as Eliot writes, "To realize that a point of view is a point of view is already to have transcended it." And to recognize fragments as fragments, to name them as fragments, is already to have transcended them not to an harmonious or final unity but to a somewhat higher, somewhat more inclusive, somewhat more conscious point of view. Considered in this way, the poem does not achieve a resolved coherence, but neither does it remain in a chaos of fragmentation. Rather it displays a series of more or less stable patterns, regions of coherence, temporary principles of order the poem not as a stable unity but engaged in what Eliot calls the "painful task of unifying."

Within this perspective any unity will be provisional; we may always expect new poetic elements, demanding new assimilation. Thus the voice of Tiresias, having provided a moment of authoritative consciousness at the centre of the poem, falls silent, letting events speak for themselves. And the voice in the last several lines, having become conscious of fragmentation, suddenly gives way to more fragments. The polyphony of The Waste Land allows for intermittent harmonies, but these harmonies are not sustained; the consistencies are not permanent. Eliot's method must be carefully distinguished from the methods of his modernist predecessors. If we attempt to make The Waste Land conform to Imagism or Impressionism, we miss its strategy and miss its accomplishment. Eliot wrenched his poetry from the self-sufficiency of the single image and the single narrating consciousness. The principle of order in The Waste Land depends on a plurality of consciousnesses, an ever-increasing series of points of view, which struggle towards an emergent unity and then continue to struggle past that unity.

From A Genealogy of Modernism: A study of English literary doctrine 1908-1922. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1984. Copyright © 1984 by Cambridge UP. Reprinted by permission of the author.

Calvin Bedient

This might be as fair a place as any to take the pulse of the notion of a single and unifying protagonist in The Waste Land.

Again, the argument is that this notion has not been sufficiently entertained and tested in earlier commentary on Eliot. Stanley Sultan's few pages on the subject in Ulysses, The Waste Land, and Modernism form--as will be more fully noted--the one substantial, and neglected, exception.

As has perhaps been demonstrated, part I presents no obstacles to reading the poem in this light. On the contrary, the hypothesis of a single speaker and performer adds shadow, depth, drama, and direction to everything in the movement. It discovers a poem of far more seriousness, profundity, and complexity than Edward Said (among others) regards it as being: namely, "a collection of voices repeating and varying and mimicking one another and literature generally."

Certainly the original working title, "He Do the Police in Different Voices," implies the presence of a single speaker in the poem who is gifted at "taking off" the voices of others--just as the foundling named Sloppy in Dickens's Our Mutual Friend is, according to the doubtless biased and doting Betty Higden, "a beautiful reader of a newspaper. He do the police in different voices." This speaker has a flair for tones of criminality, sensationalism, and outrage--the whole gamut of abjection and judgment; or so the title implies. He shows a relish for such tones, he is virtuosic at rendering them. The working title was thus itself a harsh judgment on the protagonist (whom it travesties). All speech is abjection? The very impulse to perform voice is suspect? A complicity in the fascination of crime--say, murder? To create and to murder are near akin? These severe intimations are of a piece with the contemptus mundi of the poem.

The hypothesis of an all-centering, autobiographical protagonist-narrator is not only consistent with the working title; it explains the confident surfacing, in the latter part of the poem, of an unmistakable religious pilgrim. Unless this pilgrim can be shown to develop (to inch, scramble, flee) out of a waste land that is, or was, himself, the poem splits apart into two unequal sections, a long one constituted by what Lyndall Gordon calls "the Voices of Society" and a shorter one on a lone pilgrim to elsewhere. Neither Gordon nor A. D. Moody--each so admirable on The Waste Land--connects what they concur in regarding as a pilgrim with what they might agree to call the Voices of Society. But there is no difficulty in the way of positing the former as the "doer" of the latter--as one of the social voices, yet he who surpasses them in being able to do and place them in an ironic relation to other voices, including his own.

Gordon's valuable suggestion that the poem belongs in the religio-literary category of "the exemplary life" is in fact better served by this more unifying reading. "In the lives Eliot invokes," Gordon comments, "--Dante, Christ, Augustine, the grail knight, Ezekiel--there is always a dark period of trial, whether in a desert, a slough of despond, or a hell, followed by initiation, conversion, or the divine light itself." The protagonist is not merely one among others in hell (and the "conversation" between him and Stetson, who were alive and comparatively heroic together so long ago, only makes sense in a dimension of hell); hell is not merely others; the protagonist is hell, and it is out of this hell, at once his own and collective, that, through conversion, he must climb toward the divine light. If he does the voices of others, it is because in the first instance his ears are whores to them; he dramatizes, thus, his own abjection. He is not merely one of the denizens of the waste land; he is their sum, he is sin upon sin, even sinner upon sinner--or so his self-multiplying and self-shading ventriloquism suggests. Not that he does the voices altogether helplessly; on the contrary, he gathers them in his fist like a rattlesnake's severed coils and shakes them so as to disturb his own and his readers' war-dulled, jazz-dulled, machine-dulled ears. But, in any case, he demonstrates thus--he confesses--his own hellish entanglements with secularism and the flesh. The first three parts of the poem present the equation the others = me, if in a way that proves the equation a little false (it involves a sick self-belittlement). The rest of the poem clarifies the actual opposition of others/me that endows the first three parts with insidious drama.

[. . . .]

The protagonist both suffers from and exploits this essential theatricality of voice. His nature is a poet's nature, at once powerfully secretive and helplessly "open"--empathetic, susceptible, yours for the asking. The protagonist is, in a phrase Delmore Schwartz applies to Eliot himself, a "sibylline listener." He listens in on others with the mercilessness of one who fails to hear "the silence" in their speech yet with the full dramatic sympathy of his empathic nature, too--with a tenth of that capacity for sympathy which also, at its fullest and subtlest stretch, enables him to detect the ethereal presence of an attendant "hooded" figure (part 5), or look into the heart of light.

Eliot's prose poem "Hysteria" was about just such a protohysterical, protosalvational empathy. "As she laughed, I was aware of becoming involved in her laughter and being part of it ... I was drawn in by short gasps, inhaled by each momentary recovery, lost finally in the dark caverns of her throat, bruised by the ripple of unseen muscles." Laughter is hysteria, empathy with voice is hysteria-in-the-making, acting is controlled hysteria. The protagonist "acts" the voices of others as if he had little choice in the matter, and even his "own" voice is, to him, theater, the voice of Hieronymo as he plots a Babel of other voices, plots the crash of Babel itself.

Almost helplessly many, almost incapacitated by his capacity for openness, the protagonist will nonetheless find in this susceptibility to otherness and outsidedness (a susceptibility that, largely "sympathy," makes them inward, his) his virtú and virtue, his identification with what is pure and utter: so Other that sympathy with it minimalizes his abjection, which becomes no more than a clot of sound that he must cough up, a phlegm of speech. By imbuing his protagonist with his own auditory and vocal genius of participation in the abjectness of his times and in approaches to the Absolute (for "the silence" must be heard, and speech must edge it), Eliot made his poem a barometer sensitive both to the foggy immediate air and to the atmospheric pressure high and far off, the "thunder of spring over distant mountains" (part 5). A group or medley of voices cannot attend to a charged, remote silence; for that a single protagonist was necessary, one who could both "do" the group and find in himself the anguish and strength to leave it, repressing the fatal impulse (as Moody puts it) "towards a renewal of human love" and seeking, instead, the Love Omnipotent.

From He Do the Police in Different Voices: The Waste Land and Its Protagonist. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1986.

John Xiros Cooper

The Waste Land does not merely reflect the breakdown of an historical, social, and cultural order battered by violent forces operating under the name of modernity. For Eliot the disaster that characterized modernity was not an overturning, but the unavoidable, and ironic, culmination of that very order so lovingly celebrated in Victoria's last decade on the throne. Unlike the older generation, who saw in events like the Great War the passing of a golden age, Eliot saw only that the golden age was itself a heap of absurd sociopolitical axioms and perverse misreadings of the cultural past that had proved in the last instance to be made of the meanest alloy. The poem's enactment of the contemporary social scene in "The Burial of the Dead," "A Game of Chess," and "The Fire Sermon" exhibits the "negative liberal society" in which such events and people are typical. Eliot's choice of these events and people--Madame Sosostris, the cast of characters in "A Game of Chess," and the typist--as representative of a particular society is susceptible, of course, to a political analysis, which is to say, their representativeness is not self-evident, though they are presented as if it is. The "one bold stare" of the house-agent's clerk, put back in the bourgeois context where staring is one of the major lapses in manners, does not hold up the mirror to a simple gesture, but illuminates the underlying conditions that make a mere clerk's swagger possible. What is exposed is the "fact" that clerks in general no longer know their place. What we are to make of this fact is pointedly signaled by the disgust that the specifics of the rendering provoke and the social distance generated by the Tiresian foresufferance. . . .

As its social critique was aimed negatively at the liberal ethos which Eliot felt had culminated in the War and its disorderly aftermath, The Waste Land could not visibly adopt some preliberal code of values. In the same way, the poem could not propose a postliberal, historicist or materialist ethic without an historicizing epistemology. The poem's authority rested instead on other bases that provided, not a system of ideas as the primary form of legitimation, but a new lyric synthesis as a kind of experiential authenticity in a world in which the sacred cosmologies, on the one hand, had fallen prey to astrologers and charlatans, while, on the other, the cosmology of everyday life, i.e. the financial system (the "City" in the poem), had fallen into the soiled hands of racially indeterminate and shady importers of currants and the like, among them, of course, the pushing Jews of the plunderbund. . . .

The poem attempts to penetrate below the level of rationalist consciousness, where the conceptual currencies of the liberal ethos have no formative and directive power. Below that level lay the real story about human nature, which "liberal thought" perversely worked to obscure, by obscuring the intersection of the human and the divine at the deepest levels of consciousness. That stratum did not respond to the small-scale and portable logics of Enlightenment scientism, but to the special "rationality" of mythic thought. Its "logic" and narrative forms furnish the idiom of subrationalist, conscious life. To repeat: if not on the conventional rationalist basis, where does Eliot locate the authority of The Waste Land, and authority that can save the poem from mere eccentric sputter and give it a more commanding aspect? I think it was important for Eliot himself to feel the poem's command, and not simply to make it convincing to skeptical readers; Lyndall Gordon's biography makes this inner need for strength in his own convictions a central theme in Eliot's early life. But to answer our question: the authority the poem claims has two dimensions.

The first is based on the aesthetics of French symbolisme and its extension into the Wagnerian music-drama. Indeed the theoretical affinites of Baudelaire et al. and Wagner, which Eliot obviously intuited in the making of The Waste Land, can be seen now as nothing short of brilliant. Only in our own time are these important aesthetic and cultural connections being seriously explored. From symbolisme Eliot adopted the notion of the epistemological self-sufficiency of aesthetic consciousness, its independence from rationalist instrumentality, and thus its more efficacious contact with experience and, at the deeper levels, contact with the divine through its earthly language in myth. From his French and German forebears, Eliot formulated a new discourse of experience which in the 1920s was still very much the voice of the contemporary avant-garde in Britain and, in that sense, a voice on the margins, without institutional authority. But here the ironic, even sneering, dismissal of the liberal stewardship of culture and society reverses the semiotics of authority-claims by giving to the voice on the margins an authority the institutional voices can no longer assume since the world they are meant to sustain has finally been seen through in all those concrete ways the poem mercilessly enacts. The Waste Land is quite clear on that point. We are meant to see in "The Fire Sermon," for example, the "loitering heirs of City directors" weakly giving way to the hated métèques, so that the City, one of the "holy" places of mercantilism, has fallen to profane hands, The biting humor in this is inescapable. . . .

The second dimension of the authority on which The Waste Land rests involves the new discourse on myth that comes from the revolutionary advances in anthropology in Eliot's time associated with the names of Émile Durkheim, Marcel Mauss, and the Cambridge School led by Sir James Frazer and Jane Harrison. We know that Eliot was well acquainted with these developments at least as early as 1913-14. The importance of these new ideas involved rethinking the study of ancient and primitive societies. The impact of these renovations was swift and profound and corresponds, though much less publicly, to the impact of On the Origin of Species on the educated public of midcentury Victorian life. Modernist interest in primitive forms of art (Picasso, Lawrence, and many others), and, therefore, the idioms and structures of thought and feeling in primitive cultures, makes sense in several ways. Clearly the artistic practices of primitive peoples are interesting technically to other artists of any era. Interest in the affective world or the collective mentality of a primitive society is another question altogether. That interest, neutral, perhaps, in scholarship, becomes very easy to formulate as a critique of practices and structures in the present that one wants to represent as distortions and caricatures of some original state of nature from which modernity has catastrophically departed. Eliot's interest in the mythic thought of primitive cultures, beginning at Harvard, perhaps in the spirit of scientific inquiry, takes a different form in the argument of The Waste Land. There it functions pointedly as a negative critique of the liberal account of the origins of society in the institutions of contract, abstract political and civil rights, and mechanistic psychology.

The anthropologists rescued the major cultural production of primitive societies—myth--from the view that saw these ancient narratives either as the quaint decorative brio of simple folk or, if they were Greek, as the narrative mirrors of heroic society. Instead myth, and not just the myths of the Greeks, was reconceived as the narrative thematics of prerationalist cosmologies that provided an account of the relationship between the human and the divine. Myth was also interpreted psychologically, and Nietzsche is crucial in this development, as making visible the deeper strata of the mind. If the concept is the notional idiom of reason, myth is the language of unconscious life. What Eliot intuited from this new understanding was that myth provided a totalizing structure that could make sense, equally, of the state of a whole culture and of the whole structure of an individual mind (Notes 25). In this intuition he found the idiom of an elaborated, universalizing code which was not entirely the product of rationalist thought. In addition, this totalizing structure preserved the sacred dimension of life by seeing it inextricably entwined with the profane. For the expression of this intuition in the context of an environment with a heavy stake in the elaborated codes of a rationalist and materialist world view which had subordinated the sacred to the profane, Eliot adapted for his own use the poetics of juxtaposition.

The textual discontinuity of The Waste Land has usually been read as the technical advance of a new aesthetic. The poetics of juxtaposition are often taken as providing the enabling rationale for the accomplishment of new aesthetic effects based on shock and surprise. And this view is easy enough to adopt when the poem is read in the narrow context of a purely literary history of mutated lyric forms. However, when the context is widened and the poem read as a motivated operation on an already always existing structure of significations, this technical advance is itself significant as a critique of settled forms of coherence. Discontinuity, from this perspective, is a symbolic form of "blasting and bombardiering." In the design of the whole poem, especially in its use of contemporary anthropology, the broken textual surface must be read as the sign of the eruptive power of subrational forces reasserting, seismically, the element totalities at the origins of culture and mind. The poem's finale is an orgy of social and elemental violence. The "Falling towers," lightning and thunder, unveil what Eliot, at that time, took to be the base where individual mind and culture are united in the redemptive ethical imperatives spoken by the thunder. What the poem attempts here, by ascribing these ethical principles to the voice of nature and by drawing on the epistemological autonomy posited by symbolisme, is the construction of an elaborated code in which an authoritative universalizing vision can be achieved using a "notional" (mythic) idiom uncontaminated by Enlightenment forms of rationalism.

Powerful as it is in the affective and tonal program of the poem, functioning as the conclusion to the poem's "argument," this closural construction is, at best, precarious when seen beyond the shaping force of the immediate social and cultural context. This construction, achieved rhetorically, in fact is neither acceptable anthropology, nor sound theology, nor incontestable history, but draws on all these areas in order to make the necessary point in a particular affective climate. The extent to which the poem still carries unsurpassable imaginative power indicates the extent to which our own time has not broken entirely with the common intuitive life that the poem addressed 60 years ago.

From T.S. Eliot and the Politics of Voice: The Argument of "The Waste Land." Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1987. Copyright © 1987 by John Xiros Cooper.

Louis Menand

All the difficulties with the late-nineteenth-century idea of style seem to be summed up in The Waste Land. It is, to begin with, a poem that includes an interpretation--and one "probably not in accordance with the facts of its origin"--as part of the poem, and it is therefore a poem that makes a problem of its meaning precisely by virtue of its apparent (and apparently inadequate) effort to explain itself. We cannot understand the poem without knowing what it meant to its author, but we must also assume that what the poem meant to its author will not be its meaning. The notes to The Waste Land are, by the logic of Eliot's philosophical critique of interpretation, simply another riddle--and not a separate one to be solved. They are, we might say, the poem's way of treating itself as a reflex, a "something not intended as a sign," a gesture whose full significance it is impossible, by virtue of the nature of gestures, for the gesturer to explain."

And the structure of the poem--a text followed by an explanation--is a reproduction of a pattern that, as the notes themselves emphasize, is repeated in miniature many times inside the poem itself, where cultural expressions are transformed, by the mechanics of allusion, into cultural gestures. For each time a literary phrase or a cultural motif is transposed into a new context--and the borrowed motifs in The Waste Land are shown to have themselves been borrowed by a succession of cultures--it is reinterpreted, its previous meaning becoming incorporated by distortion into a new meaning suitable to a new use. So that the work of Frazer and Weston is relevant both because it presents the history of religion as a series of appropriations and reinscriptions of cultural motifs, and because it is itself an unreliable reinterpretation of the phenomena it attempts to describe. The poem (as A. Walton Litz argued some time ago) is, in other words, not about spiritual dryness so much as it is about the ways in which spiritual dryness has been perceived. And the relation of the notes to the poem proper seems further emblematic of the relation of the work as a whole to the cultural tradition it is a commentary on. The Waste Land is presented as a contemporary reading of the Western tradition, which (unlike the "ideal order" of "Tradition and the Individual Talent") is treated as a sequence of gestures whose original meaning is unknown, but which every new text that is added to it makes a bad guess at.

The author of the notes seems to class himself with the cultural anthropologists whose work he cites. He reads the poem as a coherent expression of the spiritual condition of the social group in which it was produced. But the author of the poem, we might say, does not enjoy this luxury of detachment. He seems, in fact, determined to confound, even at the cost of his own sense of coherence, the kind of interpretive knowingness displayed by the author of the notes. The author of the poem classes himself with the diseased characters of his own work--the clairvoyants with a cold, the woman whose nerves are bad, the king whose insanity may or may not be feigned. He cannot distinguish what he intends to reveal about himself from what he cannot help revealing: he would like to believe that his poem is expressive of some general reality, but he fears that it is only the symptom of a private disorder. For when he looks to the culture around him, everything appears only as a reflection of his own breakdown: characters and objects metamorphose up and down the evolutionary scale; races and religions lose their purity ("Bin gar keine Russin, stamm' aus Litauen, echt deutsch"); an adulterated "To His Coy Mistress" describes the tryst between Sweeney and Mrs. Porter, and a fragmented Tempest frames the liaison of the typist and the young man carbuncular; "London bridge is falling down." The poem itself, as a literary object, seems an imitation of this vision of degeneration: nothing in it can be said to point to the poet, since none of its stylistic features is continuous, and it has no phrases or images that cannot be suspected of--where they are not in fact identified as--belonging to someone else. The Waste Land appears to be a poem designed to make trouble for the conceptual mechanics not just of ordinary reading (for what poem does not try to disrupt those mechanics?) but of literary reading. For insofar as reading a piece of writing as literature is understood to mean reading it for its style, Eliot's poem eludes a literary grasp.

From Discovering Modernism: T.S. Eliot and His Context. Oxford University Press, 1987. Reprinted by permission of the author.

Carol Christ

In The Waste Land Eliot, with a desperate virtuosity, presents various ways of constituting the male and female, as if in search of a poetic figuration and voice that place him beyond the conflicts that characterize his earlier poetic stances. The early sections of the poem, up to the entry of Tiresias, develop the strategy of "Portrait of a Lady." They juxtapose the meditations of a male voice with a number of female portraits: Mme. Sosostris, the wealthy woman and the working-class woman in "A Game of Chess," Marie, the hyacinth girl, and, in Eliot's rough draft of the poem, Fresca. In this collage Eliot gives the women of the poem the attributes of traditional literary character. They inhabit settings, they exist in dramatic situations, they have individual histories, and they have voices. They constitute most of the identified speakers in the first three sections of the poem, and they contain among them a number of figures for the poet: the sibyl of Cumae; Mme. Sosostris with her Tarot deck; Fresca, who "scribbles verse of such a gloomy tone / That cautious critics say, her style is quite her own"; and La Pia, who can connect "nothing with nothing." One might appropriately object that these are for the most part satiric portraits (indeed, some of them savagely satiric), but they are nonetheless the ways in which the poem locates both verbal fluency and prophetic authority.

In contrast, the male voice through which Eliot presents these women has none of the definitional attributes of conventionally centered identity. It resists location in time and space, it conveys emotion through literary quotation, and it portrays experience only through metaphoric figuration: the cruel April at the poem's beginning, the desert landscape, the rat’s alley, where "dead men lost their bones." Eliot thus turns the shifting figuration that appears as unsurety in "Portrait of a Lady" to a poetic strength. The very lack of location and attribute seems to place the speaker beyond the dilemmas of personality, as if Eliot had succeeded in creating the objective voice of male tradition. But for all this voice seems to offer, the early parts of the poem imagine men as dead or dismembered: the drowned Phoenician sailor, whose eyes have been replaced by pearls, the one-eyed merchant, the fisher king, the hanged man, the corpse planted in the garden. Thus Eliot allows us to read the sublimation of body and personality that mark the poem's voice as a repression of them as well, an escape from dismemberment by removing the male body from the text.

The one place where Eliot attaches a specific historical experience to the speaking voice of the poem -- the episode of the hyacinth girl -- supports such a reading. The episode begins with the speaker's quoting a woman who addressed him, recalling a gift he gave her: "You gave me hyacinths first a year ago." The speaker then describes his own consciousness of that moment in their relationship. When they came back from the Hyacinth garden, her arms full and her hair wet, he could not speak and his eyes failed, he was neither living nor dead, and he knew nothing, "looking into the heart of light, the silence." Perhaps in recognition of the special status that this episode has by virtue of its attachment to the poet's "I," many critics have found in it the emotional center of the poem. The moment offers some revelation of spiritual and erotic fullness ("the heart of light"), but the speaker portrays himself as unequal to it. Speech and vision fail him, and he ends the passage by borrowing the articulation of another poem ('Oed' und leer das Meer'), a ventriloquized voice that is not his own, that reveals him at a loss for words. We have here a Tiresias who, at the moment of sexual illumination, loses not only his sight but his voice as well, a seer who does not gain prophetic power from sexual knowledge. As in his early poetry, Eliot represents the moment of looking at a woman as one that decomposes his voice.

Eliot's use of visual imagery in "A Game of Chess" sustains this sense of a moment of vision evaded. For all the elaborate description of the woman's dressing table and chamber, the passage avoids picturing the woman herself, unlike its source in Antony and Cleopatra, The long opening sentence of the description -- seventeen lines long -- carefully directs the eye around what is presumably the woman sitting in the chair, but she only appears at the end of the passage, in the fiery points of her hair, which are instantly transformed into words. The passage thus finally gives the reader only a fetishistic replacement of the woman it never visualizes, a replacement for which he immediately substitutes a voice. A number of the images in "A Game of Chess" reinforce this concern with the desire to look and its repression the golden Cupidon that peeps out while another hides his eyes behind his wing, the staring forms leaning out from the wall, the pearls that were eyes, the closed car, the Pressing of lidless eyes, and in the second section, Albert’s swearing he can’t bear to look at Lil. All of the eyes that do not look in this section of the poem are juxtaposed to images of a deconstituted body, imagined alternately as male and as female: the change of Philomel, withered stumps of time, the rat's alley where dead men lost their bones, and the teeth and baby Lil must lose. As the men in the section resist looking, so they do not speak. Albert is gone, and the speaker cannot or will not answer the hysterical questions of the lady.

The poem changes its figuration of gender with the introduction of Tiresias. Eliot states in a note to the passage that "the two sexes meet in Tiresias. What Tiresias sees, in fact, is the substance of the poem" -- a declaration that critics have tended to view rather skeptically. But what Tiresias sees is the sight that the poem has heretofore evaded: the meeting of the sexes, a meeting that Tiresias experiences by identifying with the female. As the typist awaits her visitor, Tiresias asserts, "I too awaited the expected guest," and at the moment when the house agent's clerk "assaults" her, he states, "And I Tiresias, have foresuffered all," a position assumed again in the lines spoken by La Pia. Paradoxically, when the poem assumes the position of the female, male character becomes far more prominent: in the satiric portrait of the house agent's clerk, which is the first extended satiric male portrait in the poem, in the image of the fishermen, and in the extended fisherman's narrative that originally began Part IV and concludes with the death of Phlebas. As if repeating the doubleness of identification that Tiresias represents, that death affords at once the definitive separation of male identity and a fantasy of its separation of male identity and a fantasy of its dissolution as "He passed the stages of his age and youth / Entering the whirlpool."

In the final section of the poem, Eliot changes its representation of gender dramatically. He drops the strategy of character that had been the principal way in which the poem had up to this point centered its emotion and develops a voice and figuration for the speaker that remains separate from categories of gender. He accomplishes this by using both specifically religious allusions and natural images that for the most part avoid anthropomorphization. He seeks to evoke a poise from natural elements, as in the water-dripping song, which he gives a religious rather than a sexual resonance. Through the song Eliot moves the power of articulation in the poem from character to nature. The hermit-thrush sings in the pine trees, and the sound of the water for which he yearns is finally realized in the last line of the section: "Drip drop drip drop drop drop drop." As if in recognition of its separation from gender, this temporary poise immediately issues in the appearance of the third figure, "who walks always beside you[,] ... / ... hooded / I do not know whether a man or woman. . . ."

When the sexual concerns of the poem return, in the next passage, they assume a very different form than they have heretofore. Eliot does not locate them in relation to particular female characters or voices, although the image of the woman who "drew her long black hair out tight" does recall the woman in "A Game of Chess"; he evokes them through a sexual fantasy that represents the collapse of civilization as an engulfment within an exhausted and blackened vagina, suggested in the images of empty cisterns, exhausted wells, and bats "with baby faces" crawling "head downward down a blackened wall." This passage develops the technique of "Prufrock" in displacing images of sexual anxiety onto elements of the poem's landscape, such that the world itself rather than the characters within it locates its sexual malaise. These feminized images now possess the power of music and song that had been given to the water and the thrush; the woman fiddles "whisper music" on the strings of her hair, the bats whistle, and voices sing out of the cisterns and wells. Despite what would seem the movement of the power of articulation to the feminine, Eliot's figurative technique here opens the way both for the poem's resolution and for the transfer, through nature, of the power of music and song to the male poet. By shifting to a poetic mode that expresses emotion through landscape rather than through character, Eliot can achieve sexual potency in purely symbolic terms, as, in the decayed hole, the cock crows, and the damp gust comes, bringing rain. The very way in which these images resist, because of their natural simplicity and the literary allusions with which Eliot surrounds them, what would seem to be their obvious sexual symbolism is precisely their virtue, for they enable the poem to resolve its sexual conflict at the same time that it arrives at a figuration that places the poet beyond it. At the moment when the cock crows, Eliot transfers the power of articulation to the landscape, as the thunder speaks, giving the power of translation to the poet. When the poet interprets the commands of the thunder, he once again describes human situations, but he articulates them in abstract and ungendered terms, as if only a language free from the categories of gender allows him to imagine human fulfillment.

From Carol Christ, "Gender, Voice, and Figuration in Eliot’s Early Poetry." In T.S. Eliot: The Modernist in History. Ed. Ronald Bush. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Reprinted by permission of the author.

Michael North

The typist who appears next in the passage is a worker named metonymically for the machine she tends, so merged with it, in fact, that she is called a "typist" even at home. In The Education, Henry Adams proclaims his astonishment at the denizens of the new American cities: "new types, -- or type-writers, -- telephone and telegraph-girls, shop-clerks, factory hands, running into millions on millions .... " Eliot's point here seems very close to Adams's. Eliot's woman is also a "type," identified with her type-writer so thoroughly she becomes it. She is a machine, acting as she does with "automatic hand." The typist is horrifying both because she is reduced by the conditions of labor to a mere part and because she is infinitely multiple. In fact, her very status as a "type" is dependent on a prior reduction from whole to part. She can become one member of Adams's faceless crowd only by being first reduced to a "hand."

The typist is the very type of metonymy, of the social system that accumulates its members by mere aggregation. Yet this "type" is linked syntactically to Tiresias as well. In fact, the sentence surrenders its nominal subject, Tiresias, in favor of her. The evening hour "strives / Homeward, and brings the sailor home from sea, / The typist home at teatime, clears her breakfast, lights / Her stove, and lays out food in tins." The typist shifts in mid-line from object to subject, from passive to active. Does the evening hour clear her breakfast, or should the reader search even farther back for an appropriate subject, to Tiresias himself. Though this would hardly clarify the syntax, Tiresias could function logically as both subject and object, seen and seer, because, as the notes tell us, he is the typist: "All the women are one woman, and the two sexes meet in Tiresias." The confused syntax represents this process of identification, erasing ordinary boundaries between active and passive, subject and object.

On what basis can the typist merge with all other men and women to become part of Tiresias? In other words, what is the figurative relationship between the whole he represents and the part acted by the typist? The process of figurative identification seems similar to that in "Prufrock," where women are also represented as mere "arms" and where all women are also one woman. As in "Prufrock," the expansion to "all" depends on a prior reduction of individual human beings to standardized parts, just as Prufrock has "known them all already, known them all," Tiresias has "foresuffered all." His gift of prophecy, however, depends on the supposition that human behavior is repetitive, that "all" is in fact the mere repetition of a single act into infinity, enacted "on this same divan or bed." What, therefore, is the real difference between the industrial system, in which "all the women are one woman" and the identification represented by Tiresias? In which case is the typist less of a type?

The poem itself suggests that there may be no difference because Tiresias and the "human engine" are one and the same:

[North quotes from the line beginning "When the human engine" to the line ending "throbbing between two lives."]