Joseph Freeman's Introduction to Proletarian Literature in the United States

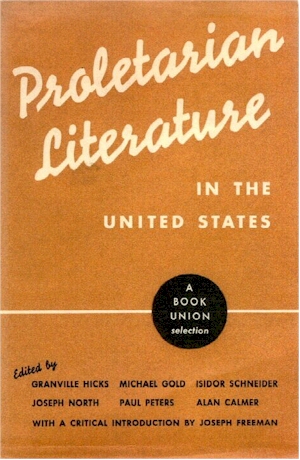

Text from the Book Flaps of

Proletarian Literature in the United States

Here is

an anthology of the best and most representative American writing in the fields of

proletarian fiction, poetry, drama, reportage and criticism. It is a milepost in the

movement toward the "left" that has characterized the younger and really vital

elements in the literature of America since the World War.

Here is

an anthology of the best and most representative American writing in the fields of

proletarian fiction, poetry, drama, reportage and criticism. It is a milepost in the

movement toward the "left" that has characterized the younger and really vital

elements in the literature of America since the World War.

In the depression years particularly the theme of proletarian literature has provoked many a literary war. Familiarity with it would have enabled many a critic and friend to dodge the snares set by ignorance.

Here is proletarian literature--the first compilation of its kind--the best that could be chosen by a distinguished editorial board.

This is no haphazard selection. On the contrary, this anthology contains works of a single high level, completely unified, organized with a purpose, and selected by a board of editors. It is a cooperative effort, the creation of a definite period in history, a definite cultural movement.

To recognize the intimate ties between art and the social milieu from which it springs--the theme of Joseph Freeman's brilliant introduction to this volume--does not necessarily transform mediocrity into talent. The authors whose works indicate the scope and excellence of this volume are winning acclaim primarily because they are good artists. But from the fate of a people they derive their stirring themes. Rural life, the factory, New York's streets, the office, the mill town, the south, the west, Jews, Yanks, Irish--these are the locales and characters which enliven proletarian fiction. Joe Hill, Haymarket, lynching, Anacostia Flats--these facets of a civilization rent asunder by a class war which concedes neutrality to none have inspired poet and story-teller and dramatist to come to grips with the stuff of which great art is born. And great art, as this anthology testifies, is being born. Poetry: The section is virtually a dynamic history of radical poetry in America over the past 15 years. Reportage: As vivid as anything to be found in America, chronicling rebellion on the American form, the football game in the Yale Bowl, the march of China's Red Army. Drama: Waiting for Lefty, The Black Pit, Stevedore, They Shall Not Die, outstanding contributions to a theatre which has no "seasons."

The broad grasp of literature and its problems, the rich fibre of the discussions, sensitivity to the esthetic and social implications of the artist's craft--all attest to the fact that Marxist criticism is winning its honored place in the world of letters.

Ten years ago these ideas were patiently and persistently expounded only by a few zealous pioneers. Today new and eloquent voices are raised in behalf of proletarian literature and its ideology. The validity of its premises, the creative scope of the men and women who subscribe to them, are illustrated by this volume, in which are gathered the most vital talents on the American sector. Already the literature of the exploited is a powerful force, consciously and brilliantly guided by its creators towards the remaking of the world.

Freeman's Introduction

Whatever role art may have played in epochs preceding ours, whatever may be its function in the classless society of the future, social war today has made it the subject of partisan polemic. The form of polemic varies with the social class for which the critic speaks, as well as with his personal intelligence, integrity, and courage. The Communist says frankly: art, an instrument in the class struggle, must be developed by the proletariat as one of its weapons. The fascist, with equal frankness, says: art must serve the aims of the capitalist state. The liberal, speaking for the middle class which vacillates between monopoly capital and the proletariat, between fascism and communism, poses as the "impartial" arbiter in this, as in all other social disputes. He alone presumes to speak from above the battle, in the "scientific" spirit.

Wrapping himself in linen, donning rubber gloves, and lifting his surgical instruments—all stage props—the Man in White, the "impartial" liberal critic, proceeds to lecture the assembled boys and girls on the anatomy of art in the quiet, disinterested voice of the old trouper playing the role of "science." He has barely finished his first sentence, when it becomes clear that his lofty "scientific" spirit drips with the bitter gall of partisan hatred. Long before he approaches the vaguest semblance of an idea, the Man in White assaults personalities and parties. We are reading, it turns out, not a scientific treatise on art but a political pamphlet. To characterize an essay or a book as a political pamphlet is neither to praise nor to condemn it. Such pamphlets have their place in the world. In the case of the liberal critic, however, we have a political pamphlet which pretends to be something else. We have an attack on the theory of art as a political weapon which turns out to be itself a political weapon.

The liberal's quarrel with the Marxists does not spring from the desire to defend a new and original theory. After the ideas are sifted from the abuse, the theories from the polemics, we find nothing more than a series of commonplaces, unhappily wedded to a series of negations. The basic commonplace is that art is something different from action and something different from science. It is hard to understand why anyone should pour out bottles of ink to labor so obvious and elementary a point. No one has ever denied it, least of all the Marxists. We have always recognized that there is a difference between poetry and science, between poetry and action; that life extends beyond statistics, indices, resolutions. To labor that idea with showers of abuse on the heads of the "Marxists-Leninists" is not dispassionate science but polemics, and very dishonest polemics at that.

The problem is: what, in the class society of today, is the relation between art and society, art and science, art and action. It is true that the specific province of art, as distinguished from action or science, is the grasp and transmission of human experience. But is any human experience changeless and universal? Are the humans of the twelfth century the same in their specific experience as the humans of the twentieth? Is life, experience, thought, emotion, the same for the knight of 1300, the young merchant of 1400, the discoverer of 1500, the adventurer of 1600, the scientist of 1700, the factory owner of 1800, the banker of 1900, the worker of 1935? Is there no difference in the "experience" grasped and transmitted by Catholic and Protestant poets, by feudal and bourgeois playwrights, by Broadway and the Theatre Union? Is Heine's social experience the same as Archibald MacLeish's? Is the love experience of Pietro Aretino the same as T. S. Eliot's?

We may say that these are all personal differences: experience is an individual affair and individuals differ from age to age. Yet nothing is more obvious than the social, the class basis of fundamental differences. Greeks of the slave-owning class, for all their individual differences, had more in common with each other than any of them has with the bourgeois poets of the Romantic school; the Romantics, for all their individual differences and conflicts, had more in common with each other than with individuals of similar temperament in Soviet letters or American fiction.

Art, then, is not the same as action; it is not identical with science; it is distinct from party program. It has its own special function, the grasp and transmission of experience. The catch lies in the word "experience." The liberal critic, the Man in White, wants us to believe that when you write about the autumn wind blowing a girl's hair or about "thirsting breasts," you are writing about "experience"; but when you write about the October Revolution, or the Five Year Plan, or the lynching of Negroes in the South, or the San Francisco strike you are not writing about "experience." Hence to say: "bed your desire among the pressing grasses" is art; while Roar China, Mayakovsky's poems, or the novels of Josephine Herbst and Robert Cantwell are propaganda.

Studying the life of their own country, Soviet critics observed that the poet deals with living people, not with abstractions. He conveys the tremendous experience of the revolution through the personal experience of individual beings who participate in it, fight for or against it, help to forward or retard its purposes, are in turn re-fashioned by it. He describes people who make friends and enemies, love women and are loved by them, work mightily to transform the land. All this the artist—if he is an artist and not an agitator—does with the specific technique of his craft. He does not repeat party theses; he communicates that experience out of which the theses arose. In so far as the artist's deepest thoughts and feelings are bound to the old regime, in so far as he experiences life with the mind and heart of a bourgeois, the experience he conveys will be seen with the eyes of the bourgeois. Such a poet will best understand all those weaknesses of the revolution which have their roots in the old, that is near and dear to him; he will be blind to the greatness of the revolution which springs from the new, that is alien, to him. He will create a false picture of Soviet reality; he will discourage people who read and believe him. But whether an artist grasps the true course of the revolution or is blind to it, his work is not divorced from science and action and class.

No party resolution, no government decree can produce art, or transform an agitator into a poet. A party card does not automatically endow a Communist with artistic genius. Whatever it is that makes an artist, as distinguished from a scientist or a man of action, it is something beyond the power of anyone to produce deliberately. But once the artist is here, once there is the man with the specific sensibility, the mind, the emotions, the images, the gift for language which make the creative writer, he is not a creature in a vacuum.

The poet describes a flower differently from a botanist, a war differently from a general. Ernest Hemingway's description of the retreat at Carporetto is different from the Italian general staff's; Tretiakov's stories of China are not the same as the resolution on that country by a Comintern plenum. The poet deals with experience rather than theory or action. But the social class to which the poet is attached conditions the nature and flavor of his experience. A Chinese poet of the proletariat of necessity conveys to us experiences different from those of a poet attached to Chiang Kai Shek or a bourgeois poet who thinks he is above the battle. Moreover, in an era of bitter class war such as ours, party programs, collective actions, class purposes, when they are enacted in life, themselves become experiences—experiences so great, so far-reaching, so all-inclusive that, as experiences, they transcend flirtations and autumn winds and star and nightingales and getting drunk in Paris cafes. It is a petty mind indeed which cannot conceive how men in the Soviet Union, even poets, may be moved more by the vast transformation of an entire people from darkness to light, from poverty to security, from weakness to strength, from bondage to freedom, than by their own personal sensations as loafers or lovers. He is indeed lost in the morass of philistinism who is blind to the experience, the emotion aroused by the struggle of the workers in all capitalist countries to emancipate themselves and to create a new world.

Here lies the key to the dispute current in American literary circles. No one says the artist should cease being an artist; no one urges him to ignore experience. The question is: what constitutes experience? Only he who is remote from the revolution, if not directly hostile to it, can look upon the poet whose experiences are those of the proletariat as being nothing more than "an adjunct, a servitor, a pedagogue, and faithful illustrator," while the poet who lives the life of the bourgeois, whose experiences are the self-indulgences of the philistine, "asserts with self-dependent force" the sovereignty of art. Art, however it may differ in its specific nature from science and action, is never wholly divorced from them. It is no more self-dependent and sovereign than science and action are self-dependent and sovereign. To speak of art in those terms is to follow the priests who talk of the church, and the politicians who talk of the state, as being self-dependent and sovereign. In all these cases the illusion of self-dependence and sovereignty are propagated in order to conceal the class-nature of society, to cover the propagandist of the ruling class with the mantle of impartiality.

In the name of art and by the vague term experience, accompanied by pages of abuse against the Communists, the ideologues of the ruling class have added another intellectual sanction for the status quo. What they are really saying is that only their experience is experience. They are ignorant of or hate proletarian experience; hence for them it is not experience at all and not a fit subject for art. But if art is to be divorced from the "development of knowledge" and the "technique of scientific action," if it is to ignore politics and the class struggle—matters of the utmost importance in the life of the workers—what sort of experience is left to art? Only the experience of personal sensation, emotion, and conduct, the experience of the parasitic classes. Such art is produced today by bourgeois writers. Their experience is class-conditioned, but, as has always been the case with the bourgeoisie, they pretend that their values are the values of humanity.

If you were to take a worker gifted with a creative imagination and ask him to set down his experience honestly, it would be an experience so remote from that of the bourgeois that the Man in White would, as usual, raise the cry of "propaganda." Yet the worker's life revolves precisely around those experiences which are alien to the bourgeois aesthete, who loathes them, who cannot believe they are experiences at all. To the Man in White it seems that only a decree from Moscow could force people to write about factories, strikes, political discussions. He knows that only force would compel him to write about such things; he would never do it of his own free will, since the themes of proletarian literature are outside his own life. But the worker writes about the very experiences which the bourgeois labels "propaganda," those experiences which reveal the exploitation upon which the prevailing society is based.

Often the writer who describes the contemporary world from the viewpoint of the proletariat is not himself a worker. War, unemployment, a widespread social-economic crisis drive middle-class writers into the ranks of the proletariat. Their experience becomes contiguous to or identical with that of the working class; they see their former life, and the life of everyone around them with new eyes; their grasp of experience is conditioned by the class to which they have now attached themselves; they write from the viewpoint of the revolutionary proletariat; they create what is called proletarian literature.

The class basis of art is most obvious when a poem, play, or novel deals with a political theme. Readers and critics then react to literature, as they do to life, in an unequivocal manner. There is a general assumption, however, that certain "biologic" experiences transcend class factors. Love, anger, hatred, fear, the desire to please, to pose, to mystify, even vanity and self-love, may be universal motives; but the form they take, and above all the factors which arouse them, are conditioned, even determined, by class culture. Consider Proust's superb study of a dying aristocracy and a bourgeoisie in full bloom; note the things which rouse pride, envy, shame in a Charlus or a Madame Verdurin. Can anyone in his senses say that these things—an invitation to a party at a duke's home, a long historical family tree—would stir a worker to the boastful eloquence of a Guermantes or a Verdurin? Charlus might be angry at Charlie Morel for deceiving him with a midinette; could the Baron conceive what it is to be angry with a foreman for being fired?

Art at its best does not deal with abstract anger. When it does it becomes abstract and didactic. The best art deals with specific experience which arouses specific emotion in specific people at a specific moment in a specific locale, in such a way that other people who have had similar experiences in other places and times recognize it as their own. Jack Conroy, to whom a Proustian salon with its snobbish pride, envy, and shame is a closed world, can describe the pride, envy, and shame of a factory. We may recognize analogies between the feelings of the salon and those of the factory, but the objects and events which arouse them are different. And since no feeling can exist without an object or event, art must of necessity deal with specific experience, even if only obliquely, by evasion and flight. The liberal critic who concludes that all literature except proletarian literature is equally sincere and artistic, that every poet except the proletarian poet is animated by "experience," "life," "human values," has abandoned the search before it has really begun. The creative writer's motives, however "human" they may be, however analogous to the motives of the savage, are modified by his social status, his class, or the class to which he is emotionally and intellectually attached, from whose viewpoint he sees the world around him.

Is there any writer, however remote his theme or language may seem at first glance from contemporary reality, however "sincere" and "artistic" his creations may be, whose work is not in some way conditioned by the political state in which he lives, by the knowledge of his time, by the attitudes of his class, by the revolution which he loves, hates, or seeks to ignore? What is the real antagonism involved in the fake and academic antagonism between "experience" on the one hand and the state, education, science, revolution on the other? This question is all the more significant since the best literary minds of all times have agreed on some kind of social sanction for art, from Plato and Aristotle to Wordsworth and Shelley, to Voronsky and I. A. Richards. Recent attempts to destroy the "Marxo-Leninist aesthetics" fall into a morass of idealistic gibberish. The term "experience" becomes an abstract, metaphysical concept, like "life" or the "Idea" or the "Absolute." But even the most abstract metaphysical concept, like the most fantastic dream, conceals a reality.

Let us examine one typical example of this metaphysical concept. Recently a bourgeois critic cited the following words by Karl Marx: "At a certain stage of their development, the material forces of production in society come in conflict with the existing relations of production, or, what is but a legal expression for the same thing, with the property relations within which they bad been at work before. From forms of development of the forces of production, these relations turn into their fetters. Then comes the period of social revolution, With the change of the economic foundation, the entire immense superstructure is more or less rapidly transformed." The critic commented that this was a true scientific description of a social law; in the future some "intellectually inventive" artist might write a poem in which this thought would be "greatly and spontaneously portrayed." But, he added, no man "can get into a position to experience a revolution concretely in those terms." Therefore, the attempt "to convey the conception in concrete images and pictures will be normally a tour de force."

Our author himself underlined the word normally. That indeed is the significant word not only in the essay, but in the entire campaign which bourgeois ideologues have been conducting against proletarian literature. If Karl Marx's law is true, as the conservative critic admits, then the process it describes involves every individual in capitalist society, even when he is utterly ignorant of Marx's formulation. The worker may never have heard of Marx, but he knows that the factory is overstocked with goods, that he is unemployed, that he is unable to purchase the goods he has produced. He may not know the phrases about the conflict between the material forces of production and the existing relations of production; he may accept the explanation of demagogues like Roosevelt, General Johnson, Father Coughlin, Huey Long, or Phil La Follette; but he knows the facts, his "experience" consists of those facts.

Let us now suppose that a given worker is a gifted story-teller, yet ignorant of Marxian theory. He accurately describes his own specific experiences at the moment when the social revolution breaks out, as many Russian, German, Hungarian, Mexican, and Chinese workers have done. Such a worker would not be writing an illustration of the Communist Manifesto any more than the bee's conduct is an illustration of Fabre's famous book. The worker's experience, however, would sustain Marx's theory, otherwise the theory would not be true. The worker's poetic rendering of the specific experience would be art, as Marx's summation of that experience is science. Nor would such a story be for the worker or the intellectual writing from the worker's standpoint a tour de force. It would be a "naturally "free" expression of experience.

But is the worker or the intellectual who identifies himself with the worker normal? Remember, the conservative critic I cited only said that normally the attempt to convey Marx's concept in concrete images and pictures would be a tour de force. From the viewpoint of the bourgeois aesthete, the worker is apparently not normal, just as the experience of the worker or of the crushed middle-classes is not experience. The "normal" poet is the bourgeois poet; "experience" is bourgeois experience. It is only if we make that false assumption that the tour de force becomes inevitable. Only when an aesthete lives the life of a bourgeois and attempts intellectually to be a "Communist" does the dualism here involved arise. For the Man in White art develops out of experience and experience is bourgeois; he can conceive of writing about proletarian life, which Marx has described scientifically, only as an intellectual tour de force, only by reading a Communist book and then "with a teacherly intention and a sufficiently deliberate ingenuity" attempt to "show" the Marxian concept, admittedly true, in images and pictures. Such a man, naturally, is compelled to a tour de force, to very bad " proletarian art"; he proceeds from the general to the specific instead of from the specific to the general.

We have had such writings in the revolutionary press, nearly always from intellectuals new to the movement. It is well known that American Marxist critics have fought against this tendency. We have maintained for years that to put a Comintern resolution in rhyme does not make proletarian poetry. It is better for the poet honestly to describe his real experiences, his doubts and inner conflicts, and the external circumstances which brought him to the revolutionary movement, than to fake his feelings by rehashing and corrupting political manifestoes which we prefer to read in their original form. But the intellectual who sympathizes with the proletariat in the abstract and continues his bourgeois life in the concrete is bound to resort to a tour de force. Such a poet can only write of his bourgeois experience; he must violate his real feelings when he attempts to translate Marxian science into art. It is when the intellectual describes his own conflicts sincerely that he create revolutionary art; it is when he has transformed his life, when his experience is in the ranks of the advanced proletariat that he begins to create proletarian art.

Art varies with experience; its so-called sanctions vary with experience. The experience of the mass of humanity today is such that social and political themes are more interesting, more significant, more "normal" than the personal themes of other eras. Social themes today correspond to the general experience of men, acutely conscious of the violent and basic transformations through which they are living, which they are helping to bring about. It does not require much imagination to see why workers and intellectuals sympathetic to the working class—and themselves victims of the general social-economic crisis—should be more interested in unemployment, strikes, the fight against war and fascism, revolution and counter-revolution than in nightingales, the stream of the middle-class unconscious, or love in Greenwich Village.

At the moment when the creative writer sits at his desk and composes his verses or his novel or his play, he may have the illusion that he is writing his work for its own sake. But without his past life, without his class education, prejudices, and experiences, that particular book would be impossible. Memory, the Greeks said, is the mother of the muses; and memory feeds not on the general, abstract idea of absolute disembodied experience, but on our action, education, and knowledge in our specific social milieu. As the poet's experience changes, his poetry changes. The revolutionary Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Southey become reactionary with age and advancement by the ruling powers; the Goethe of Goetz becomes the Goethe of Weimar; the T. S. Eliot of The Hippopotamus becomes the T. S. Eliot of Ash Wednesday; the Lewis of Babbitt becomes the Lewis of Work of Art; the O'Neill of The Hairy Ape becomes the O'Neill of Days Without End.

The free exercise of the personality in human relations and in art is not in itself a bad thing. The social revolution aims to make these goods, like the more material goods upon which they are dependent, accessible to all rather than to a few. But as long as the mass of mankind consists of exploited workers, peasants, and "whitecollar slaves," the art that springs from "love and pride" is bound to be a limited art and in times like ours a false art. Such an art can have little real meaning for those who fight for bread. It is not from the Kremlin that the worker learns to be more interested in strikes than in "love and pride," but from life itself.

When socially-owned machines will be the slaves of men instead of men being the slaves of privately-owned machines, we may begin to think seriously about a "pure" art. Until that time, art cannot help being, consciously or unconsciously, class art. The cloak of self-dependence and sovereignty no more deprives art of its class character, or the image of the all-knowing omnipresent god deprives the church of its class character.

Why, then, do workers in the Stadium or at revolutionary meetings enjoy Tschaikowsky? Why was Lenin moved by the Appassionata? Why did Marx read Aeschylus in the original every year? Because every class, like every individual, has certain "universal" experiences. Such experience, however, changes from age to age, from land to land, from class to class. We do not really see in the tragedies of the House of Atreus what the Greeks saw in them. Something is lost to us on the one hand; on the other we understand many things about those tragedies which the Greeks did not. People brought up on modem psychology do not see Oedipus Rex with the same feelings as the Athenians; possibly there may come a generation to which the literature of antiquity will have only intellectual but no emotional significance, satisfying curiosity about the past without stirring feelings about the present. Certainly the plays of Calderon cannot have the same meaning for a twentieth-century atheist as for a seventeenth-century Catholic. But from all literature, since it deals with human experience, we are able to extract analogies. What was realism for the Greeks is metaphor for us—that is, truth apprehended through analogy. The specific external motives which prompted Beethoven to compose the Appassionata may no longer exist; yet the same mood of passion and longing may be aroused in us by other things, and it is that mood which we recognize in the composition. This is much more true of music than of literature, since music achieves the greatest abstraction from the specific.More significant is the question: why do not composers today write like Beethoven or Tschaikowsky? Why do not writers compose like Aeschylus? Why is Stravinsky's setting for the three psalms so different in structure and feelings from Handel or Bach? Because our specific experiences have changed and with it our art.

However, the two do not change simultaneously, at the same speed. In some cases art leaps ahead of reality as dreams do; it utters wishes. More often it lags behind reality. Our feelings are older than our intellects. They change more slowly. The physicist continues to believe in the god which his science has demolished; the Bolshevik may weep at the Lady of the Camelias which evokes feelings older than the Bolshevik's intellectual concepts.

Here the problem of analogy enters. The Lady of the Camelias was itself at one time revolutionary. It could not have been written without Rousseau, without the romantic movement, without the successful struggle of the bourgeoisie for its own art. Once the de Goncourt brothers had to apologize for writing a novel about a servant girl. Decades later Michael Gold had to assert his right to describe in fiction the life of the tenements. Each class as it rises from the abyss to the surface as a result of changes in the basic economic relations of men, fights not only for political power, not only for the culture already achieved by its predecessors in history, but for its own contributions to world culture, for the expression of its own experiences in art.

But all previous ruling classes have been exploiting classes; their experiences were those of exploiters; their art was conditioned and limited by that basic fact. The proletariat, sole revolutionary class in contemporary society, is compelled by the conditions of its existence to see life from a wider viewpoint. Before we can create a classless society in which man will move from the realm of necessity to the realm of freedom, before there can be a classless art, the proletariat, through the artists who come from its ranks or who go over to it from other social classes, must produce a class art which is revolutionary because it illumines the whole of the contemporary world from the only viewpoint from which it is possible to see it steadily and to see it whole.

Like all new art, revolutionary art is bound to start crudely, as did the art of other classes when they were new. To begin with there are bound to be revolutionary novels as sentimental as the New Heloise; the artist's energies are too absorbed in the search for intellectual and emotional clarity for him to achieve immediate perfection of form. As the proletariat grows stronger, as it is educated by its struggle for power, its art and literature will grow stronger and better. In Russia we have in seventeen brief years seen the development of proletarian literature from the early agitational verses to And Quiet Flows the Don; in America from the sentimental socialist novels of Upton Sinclair to the mature works of the novelists represented in this volume. The vast, creative experiences of the revolutionary workers and their intellectual allies must of necessity produce a new art, an art that will take over the best in the old culture and add to it new insights, new methods, new forms appropriate for the experience of our epoch.

Every writer creates not only out of his feelings, but out of his knowledge and his concepts and his will. However crude or unformulated or prejudiced his philosophy may be, it is a philosophy and it colors his works. The revolutionary movement in America—as in other countries—is developing a generation which sees the world through the illuminating concepts of revolutionary science. The feelings of the proletarian writer are molded by his experience and by the science which explains that experience, just as the bourgeois writer's feelings are molded by his experiences and the class theories which rationalize them. Out of the experiences and the science of the proletariat the revolutionary poets, playwrights, and novelists are developing an art which reveals more forces in the world than the love of the lecher and the pride of the Narcissist. For the first time in centuries we shall get an art that is truly epic, for it will deal with the tremendous experiences of a class whose world-wide struggle transforms the whole of human society.

American writers of the present generation have passed through three general stages in their attempts to relate art to the contemporary environment. Employing the term poetry in the German sense of Dichtung, creative writing in any form, we may roughly designate the three stages as follows: Poetry and Time, Poetry and Class, Poetry and Party.

From the poetic renaissance of 1912 until the economic crisis of 1929, literary discussions outside of revolutionary circles centered on the problem of Time and Eternity. The movement associated with Harriet Monroe, Carl Sandburg, Ezra Pound, Sinclair Lewis, Sherwood Anderson, Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway was one which repudiated the "eternal values" of traditional poetry and emphasized immediate American experience. The movement had its prophet in Walt Whitman, who broke with the "eternal values" of feudal literature and proclaimed the here and now. Poetry abandoned the pose of moving freely in space and time; it focused its attention on New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Iowa, Alabama in the twentieth century.

The economic crisis shattered the common illusion that American society was classless. Literary frustration, unemployment, poverty, hunger threw many writers into the camp of the proletariat. Once they were compelled to face the basic facts of class society, such writers of necessity faced the problem of poetry and class. It was impossible to share the experiences of the unemployed worker and continue to create the poetry of the secure bourgeois. Poetry, however, tends to lag behind reality. Suffering opens the poet's eyes but tradition ties his tongue. As a member of society he was forced to face the meaning of the class struggle; as a member of the ancient and honorable caste of scribes, he continued to be burdened with antiquated shibboleths about art and society, art and propaganda, art and class.

In the past five years many writers have fought their way to a clearer conception of their role in the contemporary world. At first they split themselves into apparently irreconcilable halves. As men, they supported the working class in its struggle for a classless society; as poets, they retained the umbilical cord which bound them to bourgeois culture. The deepening of the economic crisis compelled many writers to abandon this dichotomy. The dualism paralyzed them both as men and as poets. Either the man had to follow the poet back to the camp of the bourgeoisie, or the poet had to follow the man forward into the camp of the proletariat. Those who chose the latter course accepted the fact that art has a class basis; they realized that in a revolutionary period like ours poetry is inseparable from politics. The choice was influenced chiefly by the violence of the class struggle in America today; it was also influenced by echoes of that struggle in the realm of letters. On the one hand, there were writers trained in the revolutionary movement with definite ideas on the question of poetry and class, who reasoned with the hesitant and the confused; on the other, it became more and more evident that the writers who proclaimed the "independence" of poetry from all social factors were themselves passionate and sometimes unscrupulous political partisans. The poet poised uncertainly between the two great political camps of our epoch now saw that it was no longer an abstract question of art and class, but the specific challenge: which class ?

The solution of this problem raised new ones. The working class is itself divided, and the poet feels the cleavage acutely. He now faces the question of poetry and party. There are those who say: I am, both as man and poet, on the side of the proletariat, but I cannot get mixed up with the party of the proletariat, the Communist Party. The poet cannot be above class, but he must be above party. There are others who say with Edwin Seaver: "The literary honeymoon is over, and I believe the time is fast approaching when we will no longer classify authors as proletarian writers and fellow-travellers, but as Party writers and non-Party writers."

Current discussions of this problem are fruitful. They would be more fruitful if the history of revolutionary literature were generally known. It is because most of us know little of that history that partisans of the old order are able to falsify the role of the poet. They distort the past, the present, and the future; and since they fill the pages of the conservative and liberal press, their lies and libels are bound to have some effect even on writers who are on the side of the proletariat.

The class concept of literature antedates Stalin, Lenin, and even Marx. In early bourgeois literature, the rebellious ego of the "emancipated individual" expressed itself in heroes like Werther, Rene, Obermann; in criticism, the rising progressive bourgeoisie demanded a new poetry. Denis Diderot, one of the ideological predecessors of the French Revolution, understood the class basis of the new literature and called it frankly bourgeois. Later Madame de Stael, in a book called Literature Considered in its Relation to Social Institutions (1800), argued the relative merits of classic and modern literature, in other words, feudal and bourgeois literature, urging a complete break with the feudal ideals of the past and calling for the development of a new, specifically bourgeois ideology. In 1809 Prosper de Barante wrote Tableau de Litterature Francaise au Dix-Huitieme Siecle, which started from the premise that the course of history was determined by inexorable laws and concluded that there was a necessary connection between literature and social conditions. It is not literature that governs society, he pointed out, but society that conditions literature.

The armed insurrection of the bourgeoisie against the feudal order, Napoleon's conquests, the restoration and reaction under Metternich, the revolutions of 1830 and 1848, the organization of the proletariat, the rise of the working class party fighting for the stage to follow bourgeois rule—these mighty social conflicts made political questions of prime importance in the first half of the nineteenth century. Since poets do not live in a vacuum, they took sides in the social and political struggles of the period. When the conflict became acute, the problem arose: to what extent should a poet identify himself with a party?

Ferdinand Freiligrath, one of the most famous German poets of that period, wrote in 1841: "The poet bends his knee to Bonaparte, the hero; yet d'Enghien's death-cry arouses his wrath; the Poet stands upon a watch-tower higher than the battlements of a party." Another famous German poet of that period, Georg Herwegh, then identified with the revolutionary party, replied to Freiligrath with a poem entitled Die Partie: "Party! Party! How can anyone reject it—Party, the mother of all victory? How can a poet slander such a word which bears the seed of all that is noblest? Speak out frankly like a man: are you for or against us? Is your slogan SLAVERY—or FREEDOM? The gods themselves descended from Olympus and fought on the battlements of a Party!"

Herwegh's verses—written half a century before the birth of Bolshevism—indicate the distance which Romantic poetry had travelled since the days of Novalis. They indicate, too, the relation of poetry to politics. Life in the epoch of dying feudalism and bourgeois revolution—as today in the period of decaying capitalism and proletarian revolution—forced the poet out of his ivory opium den into the political arena. And then, as now, the poet who deluded himself that he was standing "upon a watch-tower higher than the battlements of a party," found that this noble gesture of neutrality led, in practice, straight to the camp of the reaction. Freiligrath, who was so proud of standing above the battle, accepted a pension from the King of Prussia. When Georg Herwegh taunted him with this definite adherence to a party, Freiligrath understood his error, threw up his pension, joined the political poets. Eventually he became a radical, even a revolutionary poet, and worked for a time with Karl Marx on the journal which the latter edited.

The question of poetry and party which the poets of the forties raised, persisted into the eighties when Georg Brandes rose to the top of bourgeois literary criticism. Brandes himself was a bourgeois radical; he extolled the idea of nationalism, of patriotism to the bourgeois fatherland; he defended not only the right but the duty of the poet to adhere to the bourgeois party and to celebrate it in verse. It is important to note that the ideologues of the liberal bourgeoisie extolled party poetry when it was in the interest of their party. Today they raise the slogan of art for art's sake, of non-party poetry, because their party is retrogressive, and the progressive party, the party of the proletariat, must of necessity inspire poetry attacking the established order which the "neutral" critics and authors support directly or indirectly, consciously or unconsciously. In its youth the bourgeoisie demanded the right of free speech against feudal institutions; today it denies that right to the proletariat which employs it against capitalist institutions. Similarly, bourgeois critics once demanded political poetry in the interests of the progressive bourgeoisie; today they repudiate political poetry because it is in the interests of the proletariat.

In its progressive, rising phase capitalism has various groups each struggling for domination through its own party. Today, the decline of capitalism, the rising power of the proletariat, the control of one-sixth of the earth by the working class party, the spread of Communist ideas and organizations in all countries, has compelled the bourgeois groups at the top to unify their political forces. More and more the capitalist world tends to have only two major parties, the party of the capitalists and the party of the working class.

This major division was clear to the founders of the working class party. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels pointed out toward the end of the "roaring forties" that all bourgeois parties, however they may differ in their group interests, all represented the common interests of the capitalists, the maintenance of private property and the wage-system. The party of the proletariat, on the other hand, represents a class which, by its very status in contemporary society, is forced to fight not only for its own liberation but for the liberation of all who work with hand and brain, for the liberation of the mass of mankind. Its program aims at the destruction of an antiquated, oppressive social system, and the creation of a new social system corresponding to the realities of the contemporary world. Consequently the proletarian party's ideas embrace the whole of culture; they mark an advance in economics, politics, social and personal relations, philosophy, science, art, and literature.

Only a fool or a blind partisan of the bourgeoisie will claim that the advances made in these fields by the ideologists of the proletariat are dogma; only a fool or a blind partisan of the bourgeoisie will claim that communism pretends to have discovered the ultimate truths of life which will hold good for now and evermore. The teachings of communism correspond to the realities of the contemporary world. Apart from the fact that men make mistakes, the basis of communist teaching is that we live in a changing world; our truth consists in following those changes and adapting our concepts and actions to them. What is true of politics is true of poetry. The writer who comes to the movement expecting a magic formula which will solve all his problems is doomed to disappointment. The writer who holds aloof from the movement because he believes it is rigidly dogmatic is mistaken. On the contrary, it is the bourgeois writer today who is compelled to be dogmatic. Fighting on the side of a dying class he must shut his eyes to the changes around him, he must seek consolations in "eternal" values, he deludes himself that the world he loves will not essentially alter.

To followers of Karl Marx the connection between poetry, politics, and party was so obvious, that wherever the Socialist movement developed there grew up around it groups of Socialist writers and artists. Where the class struggle was latent, the Socialist movement was weak; where the movement was weak, the art it inspired was weak. Where the class struggle was sharp, the movement was strong; where the movement was strong, the art it inspired was strong. America has been no exception to this general rule. In 1901, for example, a group of American Socialists in New York revived The Comrade to meet the needs of a growing movement. Its editorial board included John Spargo and George D. Herron; its contributors included Edward Carpenter, Walter Crane, Richard Le Gallienne, Maxim Gorki, Jack London, Upton Sinclair, Ernest Crosby and Edwin Markham. The magazine—a precursor of the Masses—stated its aims as follows:

"Our mission is . . . to present to our readers such literary and artistic productions as reflect the soundness of the Socialist philosophy. The Comrade will endeavor to mirror Socialist thought as it finds expression in Art and Literature. . . . In spite of the fact that Socialists have achieved distinction in all departments of Literature and Art, the great mass of the world's disinherited . . . scarcely know of the great masterpieces of Painting, Song, and Story that have been created by men and women who have worked and are working for the great cause of Socialism." As early as 1901, The Comrade used the phrase "proletarian poet" to describe working class writers of verse.

The notion that poetry was a mystic ding-an-sich divorced from the poet's thought, will, and action was brought into the American Socialist movement on the eve of the Wilsonian era by bourgeois liberals. In the absence of a liberal party in this country, middle-class people disgusted with aspects of capitalism were forced into the revolutionary movement. In the crisis of the World War they suddenly discovered where they really belonged and crawled back to the bourgeois camp. One or two of them who wished to retain a foot in each cam, solved their problem for a time by supporting the proletariat in politics and the bourgeoisie in poetry. In the pages of the Masses, which carried out the aims of The Comrade on a higher level, these gentlemen developed a consoling dichotomy: politics dealt with the class struggle, with will and action; poetry dealt with "life," which presumably had nothing to do with will, action, or the class struggle.

But in the pages of the Masses, Floyd Dell often approached art from a definite socialist viewpoint. By the summer of 1919 he was talking specifically of proletarian literature. In that year he published with enthusiastic comments a Soviet document outlining plans of the Commissariat of Education for the development of proletarian art in Russia. As any real Socialist would, he approved of the projects to democratize artistic appreciation, and to lay "the foundations of a genuine proletarian Socialist art." Moreover, on his own account, out of his Socialist convictions, Dell realised the positive qualities which animate proletarian art. He assumed correctly that "genuine proletarian Socialist art" not only stirred the worker's imagination, but also increased his knowledge and his courage and his desire to win the fight for a new society.

In the early part of 1921, another American writer raised the slogan of proletarian art. Out of his profound devotion to the working class and to the socialism in which he believed, Michael Gold presented the idea of an art voicing the revolution. "The old moods, the old poetry, fiction, painting, philosophies"—Gold observed—"were the creations of proud and baffled solitaries. . . . The art of the capitalist world isolated each artist as in a solitary cell, there to brood and suffer silently and go mad. We artists of the people will not face Life and Eternity alone. We will face it from among the people. . . . The Revolution, in its secular manifestations of strike, boycott, mass-meeting, imprisonment, sacrifice, agitation, martyrdom, organization, is thereby worthy of the religious devotion of the artist."

Gold's essay on proletarian art continued a tradition as old as the Socialist movement. Like Edwin Markham in 1901, like John Reed in 1916, he identified the future of art with the struggles of the working class for a new society. That tradition produced American novelists like Jack London and Upton Sinclair, American poets like Joe Hill, Ralph Chaplin, and Arturo Giovannitti.

In every epoch, proletarian art is identified with the political movement of the working class. During the first two decades of our century, American revolutionary writers were influenced by or directly affiliated with the Socialist Party or the I.W.W. In the third decade, they moved in the orbit of the Communist Party which emerged as the political vanguard of the workers. They were writers, and not politicians; and they developed on the periphery of the organized movement. But their outlook on life was molded by the October Revolution, and by the struggles of the workers in all countries for a similar social transformation. Around their own, independent magazine—the New Masses, founded in the spring of I926—they created the foundations of an American art and literature corresponding to the class conflicts of our epoch.

During the twenties, the New Masses group was small. It was isolated both from the mass organizations of the workers and from the mass of the intellectuals, who, despite liberal reservations, were at this time attached to the existing social system. One or two novels, occasional stories and poems, were all that American left-wing writers were able to produce in the creative field. Proletarian literature was in its propaganda stage. The handful of revolutionary writers active in the Coolidge-Hoover era devoted themselves chiefly to criticism. They analyzed contemporary American literature from a Marxist viewpoint and agitated for a conscious proletarian art. They exposed the decay of bourgeois culture before it became generally apparent, and indicated future literary trends.

In this period, the revolutionary writer suffered from a dualism which forced him to be sectarian. His social allegiance was to the proletariat; his literary peers were attached to the bourgeoisie. Hence he had no literary milieu; he worked in isolation. That was why he was prolific in critical writing, an intellectual process, and backward in creative writing, an emotional-imaginative process. He was able to tell what kind of literature the revolutionary movement needed; he was rarely able to produce it. The historic conditions necessary for such a literature did not appear until the economic crisis overwhelmed the country and altered the life of its people.

Most men of letters come from the middle classes, which have both the education and the incentive for literary production. These classes shared the pangs of the crisis together with the workers and farmers. The unemployment, poverty, and insecurity which spread over the country hit the educated classes like a hurricane; writers and artists, among others, were catapulted out of privileged positions; and many of those who remained economically secure experienced a revolution in ideas which reflected the profound changes around them. And at the very moment when our own country, to the surprise of all except the Marxists, was sliding into a social-economic abyss, the new social-economic system of the Russian workers and peasants showed striking gains.

The contrast between the two worlds loomed up above the wreckage of old illusions. Writers and artists, like other members of the educated classes, began to read revolutionary books, pamphlets, and newspapers; they came to workers' meetings; they discovered a new America, the land of the masses whose existence they had ignored. They saw those masses as the motive power of modern history, as the hope for a superior social system, for a revival and extension of culture.

At first the middle-class writer who "went left" was a divided being. As a citizen he supported Foster and Ford in the 1932 elections; he went to the aid of the striking miners in Kentucky and was beaten up by the police; he called for the liberation of Tom Mooney and the Scottsboro boys. As a writer he remained where he was. He continued to hope that the old themes of middle-class personal existence would serve as well as in the old days. But the crisis became deeper; it forced him further toward the viewpoint of the workers. There came a time when many writers who had all their lives ignored politics and economics suddenly abandoned the poem, the novel, and the play and began to write solemn articles on unemployment, fiscal policy, and foreign trade. This politicalization of the man of letters was a step toward his transformation as a poet.

One more thing was needed to complete that transformation: direct contact with the proletarian audience. At the beginning of the crisis, the writers and artists who had grown up in the working class movement and kept alive the tradition of proletarian literature, founded literary groups like the John Reed Clubs, dramatic groups like the Theatre Union, film and photo leagues, music and dance organizations. The growth of the workers' movement was accompanied by a growth of proletarian literature. The workers and their middle-class allies, in their struggles against capitalist exploitation, against fascism, against the menace of a new world war, furnish the themes of the new literature; they also furnish the audience of the revolutionary theatre and magazines.

In the past five years, American proletarian literature has made striking progress. The arguments against it are dying down in the face of actual creative achievement. Life itself has settled the dispute for the most progressive minds of America. The collapse of the prevailing culture, the pressure of the economic crisis, the ruthless oppression of monopoly capital, the heroic struggle of the workers everywhere for the abolition of man's exploitation of man—this whole vast transformation of the world through the inexorable conflict of social classes has produced a new art in this country which has won the respect even of its enemies. Abstract debates as to whether or not the revolutionary movement of the proletariat could inspire a genuine art have given way to applause for the type of drama, fiction, poetry, and reportage included in this anthology.

Literature inspired by the revolutionary working class is, broadly speaking, no new thing in America. It would be possible to issue an anthology taking us back to the early works of Jack London and Upton Sinclair, to John Reed, Arturo Giovannitti, and Floyd Dell. The present generation of revolutionary writers is, however, by force of circumstances, even more acutely aware of the class struggle. It is the offspring of the World War, the October Revolution, the Five Year Plan, the social-economic crisis of capitalism everywhere, the growing world-wide movement of the workers for a classless communist society. These factors have given our generation its own specific features; it is a generation sobered and strengthened by the intense conflict between two civilizations, a conflict in which all are compelled to take sides.

Moreover, the literary movement represented by the writers in this volume has already had a profound influence on American letters. The theatre, the novel, poetry, and criticism, have felt the impact of these invigorating ideas; even those writers who do not agree with us have abandoned the ivory tower and begun to grapple with basic American reality, with the social scene.Revolutionary literature is no longer a sect but a leaven in American literature as a whole, as was evidenced by the American Writers' Congress last spring. There, for the first time in the history of our country, leading writers met to discuss specific craft problems, general literary questions, and means of safeguarding culture from the menace of fascism and war. A literary congress was possible in this country only when in the writer's mind the dichotomy between poetry and politics had vanished, and art and life were fused. Similarly, the publishing houses, theatres, and magazines, themselves not interested in revolutionary ideas, are turning more and more to the left-wing where writers find the basic ideas which give solidity and direction to their work.

This is a recent phenomenon in American culture, arising out of the historic conditions under which we live. It has therefore been considered advisable to limit this collection of American proletarian writings largely to the past five years, to the period of the economic crisis. In a sense, the contents of this volume are a continuation of an older literary tradition inspired by the organized movement of the American proletariat. In another sense, we have here the beginnings of an American literature, one which will grow in insight and power with the growth of the American working class now beginning to tread its historic path toward the new world.

JOSEPH FREEMAN

Return to Joseph Freeman