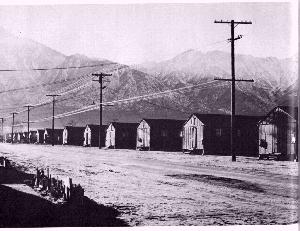

Tule Lake (California) Segregation Center

At the end of 1942, the War Department decided to organize a volunteer combat team of Nisei (second generation Japanese-American) soldiers made up of those who had passed a so-called loyalty review. The WRA saw this as an opportunity to release some of the detainees from the internment centers and prepared a companion questionnaire, titled :Application for Leave Clearance" to be filled out by all camp inmates over age 17. As it turned out, the "loyalty" or "disloyalty" of the Japanese-American internees depended principally on their answers to Questions 27 and 28. Question 27 asked the internees if they were willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States. Number 28 asked whether they would swear unqualified allegiance to the United States, and foreswear allegiance to the Japanese emperor and to any other foreign government.

For a variety of reasons too involved to discuss here, the :loyalty questionnaire" further fragmented the relations of the internees with their families and relatives, and even their friends. As an outcome of this ill-advised policy, by the fall of 1943, Tule Lake (located near the Lava Beds National monument close to the California/Oregon border) had been converted from a concentration camp to a maximum security segregation center. As the WRA expected, the number of "disloyal" internees who had not answered the questionnaire were many. Arrival of these internees from other concentration camps began in autumn and by fall of the following year, Tule Lake was the largest of the ten centers, its population peaking at 18,000.

The segregation center comprised an area of

more than 26,000 acres of sandy soil of a dry lake bed covered

with tule reed. The region was arid and averaged only ten inches

of rain annually. In the summer, the temperature often reached

100o F and in winter, which generally

arrived relatively early, thermometer readings frequently dropped

to -20oF.

The segregation center comprised an area of

more than 26,000 acres of sandy soil of a dry lake bed covered

with tule reed. The region was arid and averaged only ten inches

of rain annually. In the summer, the temperature often reached

100o F and in winter, which generally

arrived relatively early, thermometer readings frequently dropped

to -20oF.

The "camp," as it was sometimes called, was entirely surrounded by a high barbered-wire fence with guard towers spaced at regular intervals, each manned and equipped with a searchlight and machine gun. In addition, within the center but outside the detainee area, there was a large fenced-in space where a battalion of military police and a number of army tanks were kept for "security duty." Tule Lake, as well as each of the other ten centers, had a project jail or similar enclosed area where draft resisters, NO/NO boys, and the like were confined.

Following the so-called November 4, 1943 WRA Food Warehouse incident, three innocent internees were detained as suspects by the WRA Security Guards. These unfortunates were subjected to an all-night investigation, which entailed being brutally beaten to make them "confess." Then, without any medical attention, they were turned over to Army Security.

They were confined to an army tent from November 4, 1943 to early 1944 and were issued only metal cots, placed on the bare ground, and two army blankets each to ward off the frigid cold. This tent area, located in a double-fenced compound, became known as the "Bull Pen" and was situated close to the Tule Lake Hospital referred to as Area B.

Martial law was declared soon afterward and barracks were hastily constructed to house the increasing number of "suspects" and so-called "trouble-makers" who, by the spring of 1944, numbered close to 3000. Ten months later, the last of 18 inmates were released and what had become known as the Tule Lake Stockade was razed overnight. What remains now is only the Men's Project Jail.

Many touching Haiku, included in this anthology, were written during this period.

Another section of Tule Lake comprising almost 3,000 acres was set aside for farm operations outside the Center, euphemistically called the "colony." Here, some of the internees, always under guard, grew vegetables for their own camp, for its military garrison, for other camps, or for various other Army and Navy units. As with other centers, Tule Lake paid internees $12, $16, or $19 monthly, depending on whether they were farmers, technical personnel or highly-skilled professionals.

In order to make their lives more bearable, the internees tried to keep their personal routines and their lives as "normal" as possible. They commemorated religious and cultural holidays, participated in baseball games and other sports, tried to make Japanese gardens near their living quarters, and exchanged seeds and plants to embellish their particular areas as much as possible.

They also held poetry meetings where they read their haiku, in which they expressed their hopes and plans to reshape their post-war lives in America (or Japan, if they returned there).

In 1979, a plaque with the designation "California Historical Landmark No. 850-2" was placed where the main entrance to Tule Lake had been located. In recent times, a yearly tour called "Tule Lake Pilgrimage" is arranged by Japanese-American organizations. Tourists and former internees alike continue to have difficulty believing that such a concentration camp could have existed in the United States, let alone in California, only a half a century ago--at the same time that our own great democracy was locked up in a life or death struggle with Adolph Hitler's evil dictatorship.

from May Sky: There Is Always A Tomorrow: An Anthology of Japanese American Concentration Camp Kaiko Haiku. Compiled, Translated, and Prefaced by Violet Kazue de Cristoforo. Los Angeles, Sun & Moon Press, 1997.