On "Francisco, I'll Bring You Red Carnations"

Philip Levine

So would you say that your obsession with the Spanish Civil War began with these anarchists down the street?

Even earlier. It began because it was apparent to me ... coming from a Jewish household, I had a very heightened sense of what fascism meant. It meant anti-Semitism; it meant Hitler. I mean he was like the king fascist. And then there were these minor league fascists, but they essentially meant the same thing. And I saw the threat reaching right into my house and snuffing me out if something wasn't done to stop the advance of fascism. And Detroit was an extraordinarily anti-Semitic city. I don't know if you're aware of a man named Father Coughlin, who was on the radio every Sunday from Royal Oak, which is a suburb of Detroit. He had a huge church out there and he preached Hitler every Sunday. I spent most of my childhood and adolescence fighting with people who, you know, wanted to beat me up because I was Jewish. I didn't enjoy it at all. Even winning wasn't very satisfying, you weren't winning anything. So my obsession with the Spanish Civil War began during the civil war itself, which began when I was very young. The things I was hearing everywhere were true, that the Nazis and the Italians were there supporting the fascist army, and it was just more of the advance of fascism, which had already claimed Austria and during the Spanish Civil War took Czechoslovakia and began to move in on Poland, demanding the Polish Corridor. So that you didn't know where this threat was going to end. And so-called western democracies were doing a pathetic job of combating it. They were looking the other way. And if you look into the history you know that they wanted fascism to succeed. It was a way of eliminating communism ...

When you were a kid you talked about Ferrer Guardia?

Yes. He was a hero. There's something that the history books often refer to as the Terrible Week, because the history books are written by capitalists. And he had a free school in Spain, and he was considered a terrible troublemaker because of this. And a guy who worked for his school went to Madrid and tried to assassinate the ... king's son who had just gotten married.... The school was closed, and he left - but he wasn't tried or anything - he left Spain. And he returned ... about two weeks before an uprising in Barcelona which lasted a week.... Ferrer was picked up along with a number of other people, but he was never in Barcelona during this uprising. And I think he was tried on Friday, sentenced on Saturday, executed on Monday ... He had no chance. He became a hero to a lot of working-class people....

What do you mean when you say you're an anarchist?

I mean I think I'm an anarchist.

Could you explain the difference between anarchism and the new right-wing libertarianism of Ayn Rand and economists like Greenspan and Milton Friedman? They go so far as to say that if they want to set up a potentially exploitive enterprise it's their business. That's their version of unbridled individual liberty.

If you're going to allow people to make all the important choices about their lives you're going to be relying on them to make decent choices. If people are going to make unwise and disgusting choices that tyrannize their brothers and sisters, then they have violated a profound anarchist tenet: you don't tyrannize other people. In accepting your own freedom you have to grant others theirs. One basis of anarchism is the appalling confidence people will act decently.

From an interview with David Remnick (Michigan Quarterly Review [1980]).

Philip Levine

You've written a lot about Spain and your attraction to modern Spanish poets

such as Antonio Machado and García Lorca. You've also been drawn to non-literary figures

of the Spanish Civil War, such as the anarchist leaders Buenaventura Durruti and Francisco

Ascaso. Why the strong identification with Spain? What drew you to anarchism?

As a young boy I was told that my ancestry was Spanish. Why my parents, both born in a

little shtetl in western Russia, would

tell me this, I have no idea. But it may have had something to do with the expulsion of

the Jews from Spain in 1492. I did

notice when I lived in Barcelona that people would just walk up to me and start speaking

Catalan, because I looked just like

them. And then the Spanish Civil War was the war of my growing up, and a great many young

men from my

neighborhood went to it. About half of them came home. So this was my war, in a sense. I

was growing up with the

mythology of it.

As I got older I began reading the histories of the Spanish Civil War. In the Hugh

Thomas history, which is sort of the official

biography of the war, I came across the anarchists. They were the ones that impressed me

the most, because they were by far

the most idealistic, and they had, I thought, the most interesting vision of the future by

far. You could also call them terrorists,

or whatever you want to call them, but their willingness to sacrifice in an endless battle

for human justice and decency --

their willingness to take everything the world could dish out and still keep coming back

-- seemed boundless. I was just so filled

with awe for them.

For a couple years, maybe four or five, I really thought of myself as an anarchist. And

then I stopped. For one thing, I

bought a house. I could no longer say, "Property is theft." I realized I wasn't

up to that ideal -- no doubt because I didn't

have the history of grief that they had. Life was becoming relatively easy for me, so I

gave up my claim to anarchism. But

these guys still remain my heroes, because of the intensity of their gift to humanity and

their vision, which was large: we are

the stewards of the earth, we don't own anything, and our function is to make it as good

as possible and to pass it on to

those who are to come. I thought that was a very beautiful vision.

And you saw it as something distinct from the socialism that you undoubtedly were

aware of and were exposed to?

Oh, yeah -- I saw it as truly revolutionary. Socialism I saw as a kind of peel-and-patch

process: peel off some of the uglier

aspects and we'll patch it up a little. But anarchism was a radical change: we'll go right

to the denominator and destroy it;

we'll start all over. We'll abolish the notion of private property, we'll abolish money.

Then we'll abolish, of course, all those

relationships that are built out of money: marriage, serfdom, racism, colonialism,

consumerism, the ills of America.

Did you really think this was something that might happen?

No -- I wasn't crazy! I thought it was something I could incorporate in the way I lived --

and incorporate in my poetry.

But after four or five years I felt that if even I couldn't incorporate it in myself --

and I was given to a kind of awe

toward it -- how the hell was it going to grab onto the American earth?

from a 1999 interview with Wen Stephenson in The Atlantic Monthly. Click here for the entire interview.

Stephen

Yenser

Stephen

Yenser

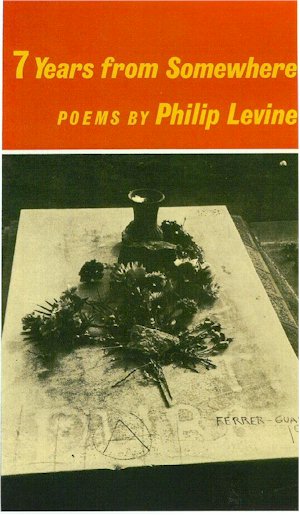

The black and white photo on the cover shows an empty vase and a couple of bunches of flowers, weighed down by rocks, resting on a stone slab covered with graffiti. We cannot know whose grave it is. No formal inscription appears, and the graffiti include at least two names, one clumsily spraypainted and barely legible, the other done with a marker and partly cropped from the photo. But then perhaps the ambiguity makes its own point, since the one name is Durruti and the other is Ferrer Guardia and they both died fighting for the same cause. As a circled A scrawled over Durruti's name suggests, it could be the grave of the Spanish Anarchist movement.

Philip Levine has frequently paid tribute to the Anarquistas. He dedicated his preceding book, The Names of the Lost, to Durruti, the leader of the radical wing of the Iberian Anarchist Federation, and several of those poems elegized Durruti and his comrades. "Francisco, I'll Bring You Red Carnations," one of the finest poems in 7 Years from Somewhere (published simultaneously with Ashes, a collection of new and older poems), honors Francisco Ascaso, another powerful figure in the FAI who died in combat. Set in a cemetery in Barcelona, it surveys "the three stones / all in a row: Ferrer Guardia, / B. Durruti, F. Ascaso" and then focuses on the latter. The swift, clean development represents Levine at his best:

For two there are floral

displays, but Ascaso faces

eternity with only a stone.

Maybe as it should be. He was

a stone, a stone and a blade,

the first grinding and sharpening

the other.

Although this is the only poem here that deals explicitly with the Spanish Civil War, one feels that it marks a center, that this gravestone and whetstone is the omphalos of Levine's world. As his earlier work testifies, from his point of view, that war no more ended in 1939 than it began in 1931. It was instead a crucial part of a continuing political struggle. We always find "The poor packed in tenements / a dozen high; the rich / in splendid homes or temples."

Those lines refer ironically to the graves and mausoleums, but the metaphor instantly reverses itself. Levine wants us to see that Barcelona also qualifies as a "city of the dead." Suffocating in "industrial filth and / the burning mists of gasoline," it could be hell - and at the same time any city in which, as he put it in an interview several years ago, "people's lives are frustrated, they're lied to, they're cheated, there is no equitable handing out of goods" . . The Barcelona laborers in "Hear Me" have the fierce, contemptuous strength of folk heroes. . . .

Strong as they are, however, and because they are so strong, their lives travesty Ascaso's "dream of the city / of God, where every man / and every woman gives / and receives the gifts of work / and care."

From "Recent Poetry," The Yale Review (1980).

Robert Hedin

In "Francisco, I'll Bring You Red Carnations" Levine pays homage to his fallen heroes buried in the cemetery of Barcelona, a setting he employs in "Montjuich" and "For the Fallen" and where, with each visit, his anarchist dream to break "the unbreakable walls of the state" is restored. There, among the 871,251 dead, he finds the same perpetuation of classes, the same visions of prosperity and squalor, as he finds in the cities of the living. Even in death, the poor are crammed into "tenements a dozen high"; the wealthy are entombed in nothing less than palaces. "So nothing has changed," Levine writes, "except for the single unswerving fact: they are all dead." There, too, he informs his martyred hero, Francisco Ascaso, of the events that have transpired since the Spanish Civil War. . . .

Like many of Levine's urban settings, Barcelona is depicted as a City fallen out of grace, its old town polluted and slum-ridden. Only two things remain from the days of the Spanish Civil War: the police who enforce the unjust laws and Ascaso's dream of the "city of God" that "goes on in spite of all that mocks it." In the end, in an obvious reference to Buenaventura Durruti, Levine writes:

We have it here

growing in our hearts, as

your comrade said, and when

we give it up with our last

breaths someone will gasp

it home to their lives.

Though the vision is depicted as an enduring one, its presence as natural as the heart's daily rhythms, it nevertheless remains a private hope. As in "Gift for a Believer," it survives on an individual basis, passed among those who are sympathetic to the anarchist cause.

How Levine envisions this new world is never fully made clear, at least for any sustained number of lines. However, all his heroes diametrically oppose any system of governing that is founded upon human subjugation. In Don't Ask, Levine echoes the politics of his anarchist heroes: "I don't believe in the validity of governments, laws, charters, all that hide us from our essential oneness. Anarchism is an extraordinarily generous, beautiful way to look at the universe. It has to do with the end of ownership, the end of competitiveness, the end of a great deal of things that are ugly." Poems such as "Gift for a Believer" and "Francisco, I'll Bring You Red Carnations" suggest the refusal of Levine's heroes to comply with the dictates of the past. Instead, they stubbornly strive to establish the conditions of essential goodness which society negates.

Indeed, at the heart of Durruti's vision - and by extension Levine's other anarchist heroes - is the desire to reverse all historical movements. In prophesying the rise of something altogether new, Durruti goes beyond the fate of the mere individual to declare the salvation of the human community at large. The result is freedom from the dehumanizing strictures of history and time of which present societies are products, and the establishment of a community founded upon cooperation and collective identity, a union of solidarity whose members are all linked "hand to forearm, forearm to hand" in fraternal embrace. In short, with the dismantling of all hierarchical power structures comes the release from the past and the subsequent rise of a dynamic communalism wherein "every man / and every woman gives / and receives the gifts of work and care."

. . . .

Of all his characters, clearly the most recurring and significant are the Spanish Civil War anarchists, primarily Buenaventura Durruti and Francisco Ascaso, whose struggles against an unjust social order Levine honors, if not nobilitates, throughout his work. More than any other, Durruti, to whom Levine dedicates The Names of the Lost, carries a utopian dream of the state, a "new world" as he calls it, freed of history and time wherein all tyranny is abolished and the individual is allowed to express the innate goodness and boundlessness of the self. In an interview published in the Montreal Star on October 30, 1936, a month before his death near the Model Prison in Barcelona, Durruti was quoted as saying: "We are going to inherit the earth. The bourgeoisie may blast and ruin this world before they leave the stage of history. But we carry a new world in our hearts." This vision, echoing the Old Testament prophecy that says the meek shall inherit the earth, is one to which Levine alludes in nearly all his major political poetry.

From :In Search of a New World: The Anarchist Dream in the Poetry of Philip Levine," in American Poetry (1986). Copyright © Lee Bartlett and Peter White.

Return to Philip Levine