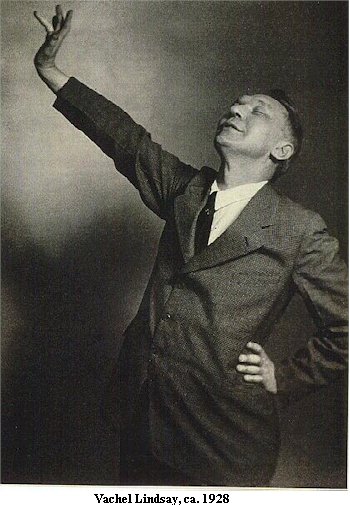

Vachel Lindsay as Performer

Accounts of Lindsay's dramatic recitation style from witnesses, biographers, and Lindsay's own letters.

Quite at odds with the

poets we now know as the High Modernists, who saw poetry principally as an artifact, as a

visual and spatial form, Vachel Lindsay envisioned poetry fundamentally as a peformance,

as an aural and temporal experience. Moreover, poetry was not meant simply to be read or

even recited, but to be chanted, whispered, belted out, sung, amplified by gesticulation

and movement, and punctuated by shouts and whoops. Lindsay's performances of his poetry

were legendary, even in a period when audiences were accustomed to similar theatrics on

the Chautauqua circuit, at revival meetings, and in vaudeville. A sampling of the many

accounts of Lindsay's performances follows.

Quite at odds with the

poets we now know as the High Modernists, who saw poetry principally as an artifact, as a

visual and spatial form, Vachel Lindsay envisioned poetry fundamentally as a peformance,

as an aural and temporal experience. Moreover, poetry was not meant simply to be read or

even recited, but to be chanted, whispered, belted out, sung, amplified by gesticulation

and movement, and punctuated by shouts and whoops. Lindsay's performances of his poetry

were legendary, even in a period when audiences were accustomed to similar theatrics on

the Chautauqua circuit, at revival meetings, and in vaudeville. A sampling of the many

accounts of Lindsay's performances follows.

In Kansas, on his 1912 walking tour from Illinois to New Mexico, Lindsay wrote home about an unfavorable reaction to one of his readings, later recounted in Adventures While Preaching the Gospel of Beauty:

I had an amusing experience at the town of Belton. I had given an entertainment at the hotel on the promise of a night's lodging. I slept late. Over my transom came the breakfast-table talk. "That was a hot entertainment that young bum gave us last night," said one man. "He ought to get to work, the dirty lazy loafer," said another.

The schoolmaster spoke up in an effort not to condescend to his audience: "He is evidently a fraud. I talked to him a long time after the entertainment. The pieces he recited are certainly not his own. I have read some of them somewhere. It is too easy a way to get along, especially when the man is as able to work as this one. Of course in the old days literary men used to be obliged to do such things. But it isn't at all necessary in the Twentieth Century. Real poets are highly paid." Another spoke up: "I don't mind a fake, but he is a rotten reciter, anywhow. If he had said one more I would have just walked right out. You noticed ol' Mis' Smith went home after that piece about the worms." Then came the landlord's voice: "After the show was over I came pretty near not letting him have his room. All I've got to say is he don't get any breakfast."

I dressed, opened the doorway serenely, and strolled past the table, smiling with all the ease of a minister at his own church-social. In my most ornate manner I thanked the landlord and landlady for their extreme kindness. I assumed that not one of the genteel-folk had intended to have me hear their analysis. 'Twas a grand exit. Yet, in plain language, these people "got my goat." I have struggled all morning, almost on the point of ordering a marked copy of a magazine sent to that smart schoolmaster. "Evidently a fraud!" Indeed!

In Adventures While Preaching the Gospel of Beauty, Lindsay also wrote of oratorical successes on his walk through Kansas, including the following incident in Raymond, Kansas, on Independence Day 1912:

I walked down the street. Just as I had somehow anticipated, I spied out a certain type of man. He was alone in his restaurant and I crouched my soul to spring. The only man left in town is apt to be a soft-hearted party. "Here, as sure as my name is tramp, I will wrestle with a defenceless fellow-being."

Like many a restaurant in Kansas, it was a sort of farmhand's Saturday night paradise. If a man cannot loaf in a saloon he will loaf in a restaurant. Then certain problems of demand and supply arise according to circumstances and circumlocutions.

I obtained leave for the ice-water without wrestling. I almost emptied the tank. Then, with due art, I offered to recite twenty poems to the solitary man, a square meal to be furnished at the end, if the rhymes were sufficiently fascinating.

Assuming a judicial attitude on the lunch-counter stool he put me in the arm-chair by the ice-chest and told me to unwind myself. As usual, I began with The Proud Farmer, The Illinois Village and The Building of Springfield, which three in series contain my whole gospel, directly or by implication. Then I wandered on through all sorts of rhyme. He nodded his head like a mandarin, at the end of each recital. Then he began to get dinner. He said he liked my poetry, and he was glad I came in, for he would feel more like getting something to eat himself. I sat on and on by the ice-chest while he prepared a meal more heating than the morning wind or the smell of fire-crackers in the street. First, for each man, a slice of fried ham large enough for a whole family. Then French fried potatoes by the platterful. Then three fried eggs apiece. There was milk with cream on top to be poured from a big granite bucket as we desired it. There was a can of beans with tomato sauce. There was sweet apple-butter. There were canned apples. There was a pot of coffee. I moved over from the ice-chest and we talked and ate till half-past one. I began to feel that I was solid as an iron man and big as a Colossus of Rhodes. I would like to report our talk, but this letter must end somewhere. I agreed wtih my host's opinions on everything but the temperance question. He did not believe in total abstinence. On that I remained non-committal. Eating as I had, how could I take a stand against my benefactor even though the issue were the immortal one of man's sinful weakness for drink? The ham and ice water were going to my head as it was. And I could have eaten more. I could have eaten a fat Shetland pony.

At the first performance of "The Congo," before a gathering of parents, neighbors, and other residents of Springfield, Illinois, Lindsay's hometown; Elizabeth Ruggles, The West-Going Heart: A Life of Vachel Lindsay, 215:

When the citizens saw him stand up and throw back his head and heard him emit his barbaric "Boomlays" ("Simply bellowing," remarked one of them), when they saw his eyes begin to roll like a man's in a fit and his hands shoot from the cuffs of his dress suit and jab the air and his body rock and shoulders weave to the tom-tom beat of "Mumbo-Jumbo, God of the Congo," they sat at first stunned.

The performance took seven minutes. As it went on and on, a few people turned away their heads to hide their embarrassment but many more let out snorts and giggles that swelled a rising wave of laughter.

At a Chicago literary soirée hosted by Poetry magazine to honor William Butler Yeats, prior to which Poetry editor Harriet Monroe had supplied the Irish poet with a copy of Lindsay's General William Booth Enters into Heaven (Lindsay was last on the program, to read "The Congo"); Ruggles The West-Going Heart, 216-18:

"This poem [referring to "General Booth"] is stripped bare of ornament," said Yeats. "It has an earnest simplicity, a strange beauty, and you know Bacon said, 'there is no excellent beauty without strangeness.'" . . .

It was the end of an overlong program. The weary listeners had had enough and some were on their feet ready to go home, but Lindsay's beginning lines, droning and pulselike, arrested them. . . . "That 'Boom'" [the third of three "booms" filling the seventh line], says an ear-witness, "shook the room, but Mr. Lindsay chanted on." . . .

This was an audience of Lindsay's peers, one prepared by Yeats' tribute to receive the strangeness with the beauty. It began to sway in sympathy as he chanted the next lines. . . .

And then, transported, and those in front transported with him, as he rocked on the balls of his feet--his eyes blazing, his arms pumping like pistons--he sang of skull-faced witchmen . . . of Death, the torch-eyed elephant . . . finally, with high and jubilant voice, [dropping] to a marveling whisper on the last line, of the redemption of the dark race through faith. . . .

The audience burst into applause. The Negro waiters against the walls applauded. The guest of honor, jerked from the misty kingdom of his Celtic imaginings, must have felt like one who pats a kitten and sees it turn into a lion, and there were bravos from Lindsay's fellow midwesterners, persuading him into reciting General Booth.

An appreciation by Randolph Bourne; quoted in Robert F. Sayre, "Vachel Lindsay: An Essay," 8:

You must hear Mr. Lindsay recite his own "Congo," his body tense and swaying, his hands keeping time like an orchestral leader to his own rhythms, his tone changing color in response to the noise and savage imagery of the lines, the riotous picture of the negro mind set against the weird background of the primitive Congo, the "futurist" phrases crashing through the scene like a glorious college yell,--you must hear this yourself, and learn what an arresing, exciting person this new indigenous Illinois poet is."

At a poetry reading given by Lindsay at Yale University; Henry Seidel Canby, American Memoir, 295:

The nice boys from the ivory towers of the best schools and the Gothic dormitories of Yale tittered at first. But as he began to swing the persuasive rhythms of General William Booth Enters Into Heaven and The Congo, and as the rich imagery lifted the homely language into poetry, they warmed, and soon were chanting with him. Yet to them it was only a show--America, a rather vulgar America speaking, but not literature as they had been taught to regard literature.

The day after a performance to an audience in Brownsville, Texas, as recorded in a letter from Lindsay to Elizabeth Mann Wills (a student of Lindsay's while he taught junior college in Gulfport, Mississippi, with whom he fell in love); Lindsay, Letters, 297-98:

Whitman never saw the America I have seen and loved. The group of Brownsville neighbors who came in to hear me could total half a million or a million--if all my audiences were added up these ten years. And they--my audiences--always evoke the same mood that was evoked in Brownsville, and always my audience loves me--as the Brownsville people did. . . . Now Whitman in his wildest dreams was only a pretended troubadour. He sat still in cafes--never such a troubadour for audiences as Bryan or a thousand Chautauqua men. He was an infinitely more skillful writer than any other American. But I can beat him as troubadour.

As regarded by Edgar Lee Masters, in his biography of Lindsay; Vachel Lindsay, 310-11:

We have seen that Lindsay himself said that poetry is for the inner ear. The Higher Vaudeville, as he termed it, of reciting, chanting, or singing poems, makes for loudness, for triviality, for a tour de force, and for vulgarization of nuances and delicate tones. In his hands, and though he was a master platform poet, it fell into a stunt, a spectacle, that annoyed him infinitely at last, when to ask him to recite "The Congo" was to fill him with writhing nerves. All this chanting, reciting, and acting is akin to the mixed art of grand opera. It is not poetry. . . . At the beginning there was some literary judgment of an ex-cathedra sort which welcomed the return of chanting as a sign of great art restored. That was a silly phase of the hour's intoxication with the new poetry . . . .

As regarded by Elizabeth Hardwick, reviewing Masters's and Ruggles's biographies; "Wind from the Prairie,"10:

That evening Vachel Lindsay recited the whole of "The Congo," and was apparently "well-received" in spite of its being over two hundred fiercely resounding lines. This most extraordinary embarrassment in our cultural history achieved a personally orated dissemination scarcely to be credited. Anywhere and everywhere he went with it--the Chamber of Commerce, high schools, ladies' clubs, the Lincoln Day Banquet in Springfield, the Players Club in New York, where Masters tells that its noise greatly irritated certain members.

As regarded by Robert Frost, in an interview; quoted in Paul H. Gray, "Performance and the Bardic Ambition of Vachel Lindsay," 221-22:

I was as happy about Vachel as we jealous poets, artists can be, you know. He was one I could be happy about. . . . Vachel was one of these disarming people, very good boy, and one of the real kind of genius, you can call it, you can say there was [something] a little strange about him, lofty, and he did some very crazy things and he knew how to do them without trying. Some of these poets seem to get in a corner and gnaw their fingernails and try to get a dark corner, you know, and try to go crazy so they will qualify. There's none of that in Vachel. He was just crazy in his own right; he did some of the strangest things.

Return to Vachel Lindsay