On Spoon River Anthology

Ernest Earnest

on the Popularity of Spoon River Anthology

Of course what made Spoon River Anthology immediately popular was the shock of

recognition. Here for the first time in America was the whole of a society which people recognized - not only that part of it reflected in writers of the genteel tradition. Like Chaucer's pilgrims, the 244 characters who speak their epitaphs represent almost every walk of life--from Daisy Frazer, the town prostitute, to Hortense Robbins, who had travelled everywhere, rented a house in Paris and entertained nobility; or from Chase Henry, the town drunkard, to Perry Zoll, the prominent scientist, or William R Herndon, the law partner of Abraham Lincoln. The variety is far too great for even a partial list. There are scoundrels, lechers, idealists, scientists, politicians, village doctors, atheists and believers, frustrated women and fulfilled women. The individual epitaphs take on added meaning because of often complex interrelationships among the characters. Spoon River is a community, a microcosm, not a collection of individuals.from Ernest Earnest, "Spoon River Revisited." Western Humanities Review 21 (1967): 59-65. p. 63

Charles E. Burgess on The Midwestern Village

in Spoon River Anthology

The midwestern village of several thousand persons in the late nineteenth century, cannot be compared intellectually to the moribund rural hamlets of today, culturally anesthetized by television, the Reader's Digest, and the outpourings of book clubs. True, the villages of Masters' time did know conformity, isolation, poverty, and ignorance--and how effectively he portrayed these shortcomings!--but a surprising number of villagers lived active, cosmopolitan lives of travel and of the mind. If they lacked continuous urban diversions and broadening, they escaped the city's inconveniences and petty distractions. In the quiet village milieu there was a comforting sense of civilized ease that came with the transition from a rough pioneer society to a stable community buttressed by traditions. Many minds there found excitement in following and contributing to the courses of science and philosophy or in joining the effort toward mature American literature and criticism.

from Charles E. Burgess. "Master and Some Mentors" (175-201).

John Hallwas on The Mythology of Spoon River

Masters recast his personal experience as public experience through the focusing and intensifying power of myth. His Midwest was a New World Eden that had degenerated under the influence of a corrupt, materialistic group that, since the time of Alexander Hamilton (Jefferson's political enemy), had not worked for the democratic ideal. He later depicted that historical process in The New World, but he expressed that mythic view for the first time in Spoon River Anthology. Masters created the series of epitaph-poems to clarify the American cultural dialectic that he had internalized, just as Faulkner created a myth of the South for the same purpose. In the process, Masters brought the unpoetic lives of everyday Americans into poetry for the first time and used his characterizations to symbolize his mythic vision - without realizing, of course, that it was mythic. Spoon River Anthology is, then, not only a kind of fragmented "Song of Myself," it is a more pessimistic version of Whitman's Democratic Vistas, focused on the triumph of the forces of disorder and decline in turn-of-the-century America. But within that account of a discordant, aimless, corrupted--and, hence, degenerated--society, the poet-hero struggles to secure the Jeffersonian vision and to place it in poetic "urns of memory," as Webster Ford says, where it may yet inspire cultural restoration. Once Masters's purpose and perspective are recognized, everything in the Anthology is absorbed into his powerful mythic image, and the book has remarkable wholeness and significance.

Indeed, Spoon River Anthology is culturally important because it reveals the inherent contradictions in the myth of America and the potentials for good and evil that such a cultural myth contains. First of all, the Adamic American is an isolated, self-dependent figure who has no place in the Garden of the World, the social utopia that America is devoted to establishing. Hence the triumphant Elijah Browning, who creates himself in his own image as prophet-poet, achieves that identity by escaping from society. His New World Eden is the mountaintop, where he stands alone before the universe, responds to "the symphony of freedom" and achieves transcendence. As he says, "I could not return to the slopes-- / Nay, I wished not to return." But the slopes, which represent his discarded past, are also where everyone else is--and where people like Jeremy Carlisle hope "to walk together / And sing in chorus and chant the dawn / Of life that is wholly life." In other words, the myth of America reflects an ambivalent national spirit, with contradictory thrusts toward individualism and community.

from John Hallwas, "Introduction" to Spoon River Anthology (pp. 64-65).

Charles E. Burgess on the Particular, the Current,

Charles E. Burgess on the Particular, the Current,

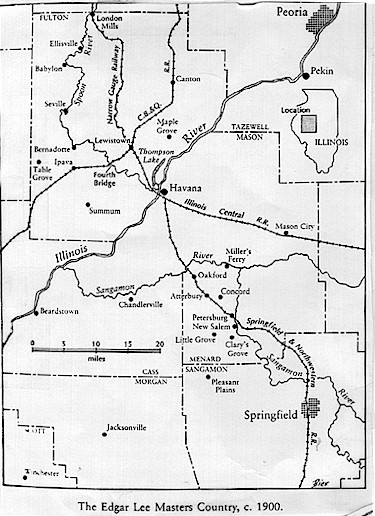

and the Local in Spoon River Anthology

It has been known since the publication in 1915 of Spoon River Anthology that Edgar Lee Masters drew much of its substance from the names, personalities, activities, and events of the central Illinois region where he grew to manhood. Both contemporary and current residents of the area have recognized that the book, in many senses, draws on community history. Scholars have agreed that matter was vital source material of the landmark in modern American poetry. Less well realized has been the role of communities of Masters's youth in the artistic and psychological stimulating of his expression. Such stimuli did exist, strong enough to impel him to use the region, a quarter of a century after he had left it, as the base of his most memorable work. That interval gave him the widened experience and the intellectual perspective necessary to impart to Spoon River Anthology senses of universality of subject, place, and time. Yet the broadening into a recognizable picture of many societies of many times did not diminish the functional importance of the book's particulars. In the use of the specific sources lies Spoon River Anthology's verisimilitude. The particulars were so strongly etched in Masters's mind and were brought forth with such sincere exactness in his writing that they were quite recognizable to people acquainted with the same communities--although seen from other lights, usually, by these persons.

In a larger sense, Masters--by 1915 an attorney of substantial reputation--was dealing in justice in creating Spoon River Anthology. He wanted to see that due praise was given to the sturdier spirits who had wrested the region from the wilderness of physical nature or who had, in later times, stood as bulwarks against the consequences of corrupt or weak human nature.

from Charles E. Burgess, "Masters and Some Mentors" p. 105.

Return to Edgar Lee Masters