On "An Octopus"

|

Patricia C. Willis

In

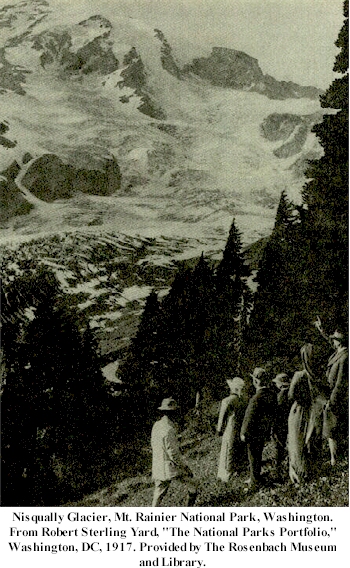

1922, Marianne Moore made the first of two trips to Bremerton, Washington, for long summer

visits with her brother. On the first trip, the family traveled up to Paradise Park on

Mount Rainier for an overnight stay. Moore photographed the dramatic Nisqually Glacier and

took close-ups of alpine flowers. She and her brother joined a hiking party and climbed up

to the ice caves, the greatest distance visitors can reach without full climbing gear.

In

1922, Marianne Moore made the first of two trips to Bremerton, Washington, for long summer

visits with her brother. On the first trip, the family traveled up to Paradise Park on

Mount Rainier for an overnight stay. Moore photographed the dramatic Nisqually Glacier and

took close-ups of alpine flowers. She and her brother joined a hiking party and climbed up

to the ice caves, the greatest distance visitors can reach without full climbing gear.

Back in New York, Moore began a long poem about Adam and Eve in paradise, but she was soon to divide it into "Marriage" and "An Octopus." Her working notes show her in the process of making that division, writing:

An octopus of ice

so cool in this the age of violence

* * *

one says I want to be alone

the other also I [would] like to be alone

why not be alone together

and further down, on the same page,

Marriage

with its resplendent properties

Later, the poem about Mt. Rainier emerged as a separate work:

An Octopus

of ice. Deceptively reserved and flat.

it lies "in grandeur and in mass"

beneath a sea of shifting snow-dunes;

And the visit to the ice caves is recalled in "’grottoes from which issue penetrating draughts which make you wonder why you came.’"

[Above figure is an autograph draft of "An Octopus" and "Marriage" (1923), Rosenbach Collection]

From Marianne Moore: Vision into Verse. Philadelphia: The Rosenbach Museum and Library, 1987.

A. Kingsley Weatherhead

One of the most interesting and complex poems in which the meaning resides in the relationship between the two kinds of literal vision is "An Octopus." The poem is complex partly because its subject is complex. Its subject is truth and how one may approach it; and as a part of this subject the poem is concerned to show how the general view is attended by happiness while the more penetrating one--the one which will attain to truth--precludes it. The poem has two parts between which the division is indicated. The first part presents, not exclusively, an unfallen world, perceptible by those who look at it with a bird's-eye view. The second part, again not exclusively, presents the truth as it may be approached and discerned by fallen mortals. These two themes occur also in the two poems which respectively precede and follow "An Octopus" in the Collected Poems and which, as Kenneth Burke has pointed out, are associated with it. In "Marriage," Eden appears in "all its lavishness," while in "Sea Unicorns and Land Unicorns" truth is imaged as a unicorn with "chain lightning" about its horn, "’impossible to take alive', / tamed only by a lady inoffensive like itself. . . .’" In "An Octopus," truth is imaged by the glacier, with "the lightning flashing at its base"; and the discipline required in approaching it--largely a matter of being inoffensive--is detailed:

It is self-evident

that it is frightful to have everything afraid of one;

that one must do as one is told

and eat rice, prunes, raisins, hardtack, and tomatoes

if one would ‘conquer the main peak of Mount Tacoma,

this fossil flower concise without a shiver. . . .’

The terms one must accept in order to climb are, of course, a metaphor for the self-discipline of clear perception and "relentless accuracy" that the poet accepts prior to the discovery and utterance of truth in her poetry. The vision of the truth at the end of the poem--a vision not brashly arrogated but earned by the discipline--is a harsh one: the glacier

. . . receives one under winds that 'tear the snow to bits

and hurl it like a sandblast

shearing off twigs and loose bark from the trees'.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . the hard mountain 'planed by ice and polished by the wind'—

the white volcano with no weather side;

the lightning flashing at its base. . . .

The first part of the poem presents on the whole a happy general view punctuated occasionally by uncomfortable glances into the real nature of things. It dwells mostly not upon the glacier itself nor the measures that must be taken to approach it but upon flora and fauna which may be observed in the surrounding park. There was, in fact, a ready-made hint for the poet that she should present this as a prelapsarian world, for the park around Mount Tacoma has the name "Paradise" and deserves it. Some of the perceptions in this romantic part of the poem are reminiscent of the tamed nature of eighteenth-century pastoral: ". . . the polite needles of the larches" are "'hung to filter, not to intercept the sunlight’"; or there are "dumps of gold and silver ore enclosing The Goat's Mirror-- / that ladyfingerlike depression in the shape of the left human foot. . . ."

The anthropomorphic distortion of real nature is extended to the descriptions of the animals: "the exacting porcupine," the rat pausing "to smell the heather," "’thoughtful beavers / making drains which seem the work of careful men with shovels,’" the water ouzel "with ‘its passion for rapids,’" and the marmot, a victim of "’a struggle between curiosity and caution.’" Among these creatures are the guides, presented as parts of the happy animal kingdom, who have withdrawn to this paradise from the complex world of hotels and are therefore safe in sloughing off their protective covering as animals sometimes do:

those who 'have lived in hotels

but who now live in camps--who prefer to';

the mountain guide evolving from the trapper,

‘in two pairs of trousers, the outer one older,

wearing slowly away from the feet to the knees'. . . .

Enjoyment of this paradise depends upon ignorance and therefore upon the imperfection of vision. Some of the creatures here are so placed that they have a vantage point from which to view this world; and for the sake of their felicity it is as important that they should not see clearly as that S. Capossela, judging winners from his cupola, should. He is concerned to find truth; his felicity is not under consideration. Similarly, the poet may arrive at truth by her fallen approach; but the animals' happiness is contingent upon their avoiding it. The passage "He / sees deep and is glad" from "What are Years?" might seem at first sight to offer an opposite theory. But seeing deep here transpires, paradoxically, to be the prerogative of one who recognizes limitations. The poet's concern with the animals' felicity in "An Octopus" reminds one of her admitted tendency upon encountering animals "to wonder if they are happy."

In connection with her descriptions of the goat and the eagles the poet toys with the word "fall": to experience the sensation of a fall would be to experience the Fall. But the vision of these animals is vague enough to preclude them from knowledge: on its pedestal the goat has its eye "fixed on the waterfall which never seems to fall." The eagles are perched on places from which humans would fall, but they see nothing:

‘They make a nice appearance, don't they',

happy seeing nothing?

Perched on treacherous lava and pumice—

those unadjusted chimney-pots and cleavers

which stipulate 'names and addresses of persons to notify

in case of disaster'. . . .

The distinction made earlier between the two parts of "An Octopus" as the products respectively of the romantic view and the realistic is only a relative one. The glacier, for instance, notwithstanding the horrendous description at the end of the poem, is referred to earlier in the second part as the "fossil flower" ; while in the first part, the word "misleadingly" in the following description of the glacier gives due warning that it may not be such a docile object as it looks from a distance and as the images from human fabrication suggest:

dots of cyclamen-red and maroon on its clearly defined pseudo-podia

made of glass that will bend--a much needed invention. . . .

.........................................

it hovers forward 'spider fashion

on its arms’ misleadingly like lace. . . .

Some of the difficulty of the poem is due to its lack of recognizable structural form. As we shall see below, many of Marianne Moore’s poems have form--form gained from rhymes, rhythms, and patterned arrangements of lines. But she avoids form that results from the organization of parts--a process in which details are selected, shaped, and ordered to contribute and conform to the whole, such as the faculty of the imagination, the "shaping spirit," would follow. To subordinate particulars to a general picture is contrary to her characteristic practice; and, as will appear, it is equally uncharacteristic in Williams. When she does subordinate details, she does so to provide a foil for the kind of perception which appreciates them. For subordinating particulars for the sake of conformity, she pours contempt upon the steamroller, to which details are only interesting to the extent that they can be applied to something else:

The illustration

is nothing to you without the application.

You lack half wit. You crush all the particles down

into close conformity, and then walk back and forth

on them.Sparkling chips of rock

are crushed down to the level of the parent block.

Her way in "An Octopus" is to present and appreciate the details as they appear--she is not making a map, but engaging in what Ezra Pound called a "periplum," a voyage of discovery which gives, not a bird's-eye view but a series of images linked by the act of voyaging: "Not as land looks on a map," says Pound, "but as sea bord seen by men sailing." There is, of course, a degree of recognizable order in the broad difference between the two parts of the poem. But a too exact structural control would defeat the poet’s aim, which is to accommodate fragments which may perhaps give "piercing glances into the things.'" Then "An Octopus" may also be properly thought of as a poem in which discoveries are made by means of the fanciful relationships that are established: that is, one may conceive that in the act of composition, in the act of relating its fanciful items, truths that the poet had not initially intended to demonstrate became manifest in the poem. It is possible to suppose that as she read about the gay living the fauna and flora in Paradise Park enjoyed despite the proximity of the horrendous glacier, she experienced one of the truths the poem now conveys, that one may live in innocence and felicity by confining attention to immediate particular realities and avoiding the vast abstractions--an existence which is not less a paradise for being a fool's paradise. Or it is possible to imagine that, in the assortment of facts about Mount Tacoma assembled by fancy, the disciplines the mountain imposes upon its climbers flashed into recognition as analogous to the terms which the search for moral truth imposes upon a poet. If one may speak guardedly of discovery in this way, one may recognize it as a product of fancy.

The phrase above about piercing glances comes from the poem "When I Buy Pictures." Throughout the poetry, images are often presented as pictures, sometimes with the employment of the terms of painting; and often the pictures are sentimental. One example is the first view of the town in "The Steeple-Jack"; another is the goat in "An Octopus," which, watching the panorama with a romantic gaze, is itself deliberately presented as an objet d'art on a pedestal "in stag-at-bay position" as sentimental as one of Landseer's creations:

black feet, eyes, nose, and horns, engraved on dazzling ice-fields,

the ermine body on the crystal peak;

the sun kindling its shoulders to maximum heat like acetylene,

dyeing them white--

upon this antique pedestal.

But in the poem concerned with buying pictures, or pretending to own them rather, the poet appears to dislike the kind of picture which is too strongly bent upon making a point. She says,

Too stern an intellectual emphasis upon this quality or that detracts

from one's enjoyment.

It must not wish to disarm anything; nor may the approved triumph

easily be honoured--

that which is great because something else is small.

One assumes she would prefer Brueghel or such paintings of Dürer as provide the eye with opportunity for play among phenomena. She quotes Goya, having recovered from his paralysis, as follows: "In order to occupy an imagination mortified by the contemplation of my sufferings and recover, partially at all events, the expenses incurred by illness, I fell to painting a set of pictures in which I have given observation a place usually denied it in works made to order, in which little scope is left for fancy and invention." Miss Moore comments as follows:

Fancy and invention--not made to order--perfectly describe the work; the Burial of the Sardine, say: a careening throng in which one can identify a bear's mask and paws, a black monster wearing a horned hood, a huge turquoise quadracorne, a goblin mouth on a sepia fish-tailed banner, and twin dancers in filmy gowns with pink satin bows in their hair. Pieter Brueghel, the Elder, an observer as careful and as populous as Goya, "crossed the Alps and travelled the length of Italy, returning in 1555 to paint as though Michelangelo had never existed," so powerful was predilective intention.

In her own poetic practice she avoids the strong approach to a central theme, by way of the imagination for instance, preferring to dwell appreciatively among her images. A picture should be "’lit with piercing glances into the life of things’"; but a glance is not a gaze or the rapacious look of the arrogant man in "A Grave."

From The Edge of the Image: Marianne Moore, William Carlos Williams, and Some Other Poets. Seattle: U of Washington Press, 1967. Copyright © 1967 by the U of Washington Press.

The Road to Paradise: First Notes on Marianne Moore's "An

Octopus"

By Patricia C. Willis

The traveler to Seattle who arrives on an overcast day sees a somber but beautiful Puget Sound to the west. To the east, he sees the hills of the city surrounding Lakes Washington and Union, and beyond them to the southeast, nothing at all: a gray wall like any rainy vista in the lowland parts of the country. When the skies clear, however, from that wall of nothingness, the mountain "comes out," as the natives say, as if it were a sun. The vast, snowy bulk seems to arise from the sea and in its utter hugeness dominates everything east of the Pacific. The effect is startling, awesome, unforgettable. The Indians called it Tacoma, "The Mountain who is God"; the English, Mt. Rainier. The point of access to its peak, a meadow perched on the side of the great Nisqually Glacier, is called "Paradise."

Marianne Moore traveled to Paradise Park in July 1922 when she spent two days on the mountain. "An Octopus" is the record of that trip and of a second journey to the Northwest made the following summer; the poem also includes some of the sights seen on both trips along the route from New York through the Canadian Rockies to Washington.

In the following pages, I will sketch the biographical circumstances for the poem, through them examine the method of composition and the poem's organization, and then focus on one major set of images: Mt. Rainier and the references to Greece.' I will consider the first extant version of the poem, a manuscript revised slightly for publication in The Dial in December 1924. This is the fullest form of a poem which Moore revised extensively over the years, usually by excising lines. The version under consideration here is printed in full at the end of the essay.2

I. Ascent to Paradise

With her mother Marianne Moore made two trips to the Northwest while her brother, John Warner Moore, was assigned as chaplain to the U.S.S. Mississippi. Warner's ship was spending a few months in drydock at Bremerton, across Puget Sound from Seattle, and he was stationed temporarily at the naval base there. The first trip, in 1922, took the Moores west by train from New York to Chicago where they boarded the Canadian Pacific for Vancouver, traveling via St. Paul, Minot in North Dakota, Banff, and Lake Louise.

Particularly interesting to a poet of the mountains was the Canadian Pacific route through the Canadian Rockies in the Lake Louise section of Alberta. The railroad climbed to its highest point there and the grade down was so steep that despite extra switches and tests of the brakes, the trains arrived at the bottom of the Selkirks with every brakeshoe smoking. Passengers were treated to an unroofed observation car for this stretch--fully open like a roller coaster. Sightseeing platforms were built along the way, and the trains stopped to allow travelers to scramble up to enjoy the views of peaks and waterfalls.

At Vancouver the Moores took the six-hour ferry ride to Seattle, arriving on 9 July. Based for a few weeks in Seattle, they went with Warner to Mt. Rainier on 25 July, traveling by car up the mountain to Paradise, and returning two days later. In early August, Marianne and her mother rented a house in Bremerton. Here they saw as much of Warner as his Navy duties would permit. They made use of the officers' club where Marianne and her brother won the mixed doubles tennis tournament on Labor Day. Their house overlooked Puget Sound and faced across to Mt. Rainier; the Olympic Range lay behind them, to the west.

On 10 September they boarded a Canadian Pacific ship at Seattle, bound for Vancouver, British Columbia, from which, accompanied by Warner, they took the Canadian Pacific train to Lake Louise. Marianne took pictures of Warner and her mother posed in front of the lake and Mt. Lefroy before going on to New York.

The second trip west, in 1923, had a slightly different itinerary. Marianne and her mother took the Delaware & Lackawanna train through New Jersey and New York to Buffalo on 13 August. Because Marianne enjoyed sailing, at Buffalo they boarded the Juniata for a winding four-day passage through the Great Lakes to Duluth. There a train to St. Paul connected them with the Canadian Pacific and the same route they had traveled west the previous summer. At Banff, Marianne bought photograph-postcards of Mt. Lefroy, Lake Agnes, Lake Louise, a mountain goat and a porcupine, and later mounted many of them in an album.3 This time they stayed in Bremerton until late October, returning home probably by the Northern Pacific across upper Montana and Glacier National Park, turning south above Fargo, North Dakota.

In July 1923, Moore wrote to her brother that she was trying to write a poem about Mt. Rainier.4 The second trip took place later that summer and gave her ample opportunity to check her facts and to acquire whatever booklets about the area she had not procured on the first trip. She did not, during her second visit, return to the mountain, but from her house in Bremerton, she could see it across the Sound in clear weather.

Both trips were important to this very close family of three who until 1922 had not been reunited for a long visit since Warner had gone to sea in 1917 and subsequently married in 1918. Thus, the three Moores had their first chance in five years to spend time together. The special excursion to Mt. Rainier was, for the future poem, a symbolic highlight. In planning the first journey to the Northwest, Warner wrote in January 1922: "Mt. Rainier is within a day's auto ride and a place I have long wished to go with those who are my very own--to go alone seemed too 'piggy,' and yet I've felt I ought to see the mountain, should I be near it, even if alone."5 He could have counted on his sister's positive response; such an adventure would suit perfectly her delight in natural history. In confirmation of the importance of this family adventure to the mountain, Marianne included her mother, her brother, and herself--albeit disguised--in "An Octopus" itself.

The Moores gave each other various nicknames over the years, always choosing animals to highlight personal traits. In "An Octopus," Mrs. Moore is the "ouzel," "with its passion for rapids and high pressured falls." Marianne is the "rat, skipping along to its burrow," a character borrowed from the poet rat in The Wind in the Willows. Warner's nickname comes from the same story; in this poem "when you hear the best wild music of the forest it is sure to be a badger." Moore knew full well that the badger-looking creature in the Northwest is actually a marmot, and at some time between submission of the manuscript to The Dial and the publication of the poem, she changed "badger" to "marmot," in the interest of accuracy, but with her brother no doubt still in mind.6

Seen

across Puget Sound from Bremerton where the Moores stayed, Mt. Rainier seems to rise

directly from the water's edge. Unlike the Rockies or other North American ranges, the

Cascades are single peaks widely spaced along the coasts of Washington and Oregon. Mt.

Rainier, the highest of the chain, stands unencumbered by lower peaks, 14,408 feet above

sea level. From the east, its top looks like a huge ice-cream cone with a scoop

removed--the result of a volcanic explosion. From the west, its whiteness turns to shades

of pink and red in the sunset and the peak is visible long after the sun has disappeared

below the horizon.

Seen

across Puget Sound from Bremerton where the Moores stayed, Mt. Rainier seems to rise

directly from the water's edge. Unlike the Rockies or other North American ranges, the

Cascades are single peaks widely spaced along the coasts of Washington and Oregon. Mt.

Rainier, the highest of the chain, stands unencumbered by lower peaks, 14,408 feet above

sea level. From the east, its top looks like a huge ice-cream cone with a scoop

removed--the result of a volcanic explosion. From the west, its whiteness turns to shades

of pink and red in the sunset and the peak is visible long after the sun has disappeared

below the horizon.

The Moores approached Mt. Rainier from this direction. Their trip to the recently constituted national park took them south from Seattle to Tacoma. From there the automobile ride to Paradise Park winds slowly upward through dense forests along scurrying streams and waterfalls. Burnt-out patches of trees are bleak reminders of lightning strikes. The strong current along boulder-filled river beds suggests the force of the snow melting on the glaciers. In 1922 there was a checkpoint at the entrance to the park where rangers counted cars and heads and controlled the one-way traffic ahead. Rules and regulations were supplied for the safety of the visitors and the park itself. The road up to Longmire Springs, and from there to Paradise, climbs and curves back upon itself, allowing brief glimpses of the peak through the trees. Finally, at Paradise, one approaches the timber line and faces the majestic Nisqually Glacier, pouring slowly from the very top of the mountain. A footpath leads up to the best view of the glacier, and there Warner photographed Marianne Moore and her mother with the glacier behind them. Warner and Marianne rented hiking gear and went with a guide to the ice caves, about an hour's steep walk up the mountain from Paradise. They spent the night at Paradise Inn, a huge rustic structure whose splendid lobby is supported by immense lodgepole pines. The meadows are filled with flowers in July, chipmunks cavort among the stones and marmots pose for photographs along the paths. At 5,400 feet, the air at the park is fresh and exhilarating; the temperature can dip toward freezing even on midsummer nights. The name "Paradise" accurately describes this spot near the top of the continent where flora, fauna, rock, and human visitors gather in an officially protected garden.

II. Initial notes for "An Octopus"

Moore began work on her poem between the two trips to the Northwest. There is a stenographer's pad containing working notes which indicate that early in 1923 she had begun a single, long poem which ultimately became two poems: "Marriage" and "An Octopus."7 The first section of this 133-page notebook contains notes devoted to the single poem. On page 5, Moore tried out two titles: "An Octopus / of ice ... / cyclamen red dots on its pseudopodia" and "Marriage / I don't know what Adam & Eve think of it by this time. . . . " There follow twenty-two pages of notes about Adam, emotion, and other images that consider human relationships, and then at page 27 we encounter this remarkable conjunction of lines:

An octopus of ice

so cool in this the age of violence

so static & so enterprising

heightening the mystery of the medium

the haunt of many-tailfeathers

these rustics calling each other by their first names

a simplification which complicates

one says I want to be alone

the other also I would like to be alone.

Why not be alone together

I have read you over all this while in silence

silence?

I have seen nothing in you

I have simply seen you when you were so handsome you gave me a

start

Here, the "octopus of ice" heads a set of phrases used directly in "Marriage"--"I want to be alone" and "so handsome you gave me a start"--and indirectly—"cool," "violence," "static emotionless." While not returning to the image of an octopus per se, Moore uses the next thirty pages to work over ideas for a poem about Adam, paradise, love, theology, divorce, woman, and hell, while including references to eagles, an impostor, a storm, and a waterfall. The controlling ideas are those expressed in "Marriage" but images later used in "An Octopus" are present.

In the middle of this section of the notebook are ten pages of reading notes, with accompanying page references, from Richard Baxter's The Saints' Everlasting Rest (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1909). This work, quoted by Moore in several of her poems, deserves mention. Richard Baxter (1615-1691) was a nonconformist English divine whose theological position earned him the sobriquet of "the Catholic of Puritanism." His eclectic theology placed him as a moderate Calvinist who upheld the doctrine of grace but believed that man could influence his own salvation by prayer and purity of heart. He was a brilliant preacher who found favor with both Cromwell and Charles II.

The Saints' Everlasting Rest, his major work, is a treatise on the prayer and attitudes needed to attain heaven or the "Everlasting Rest." It examines such topics as "What This Rest Presupposeth" and "Considering the Description of the Great Duty of Heavenly Contemplation," all buttressed with biblical citation and an occasional quotation from George Herbert's poetry. First published in 1650, it went into many editions, usually in abridged versions. A veritable bestseller, it was read by churchman and laborer alike. It is still in print.

Moore read this treatise as early as 1915 and turned to it again in 1923. The passages quoted in her notebook include one of the four used in "Marriage," all of those used in "An Octopus," and many more. Her choices for transcriptions curiously suit the tenor of both "Marriage" and "An Octopus." It was only after her close reading of this meditative text that she began to select from her notes the material for "Marriage," which she completed about July 1923, and sent to Monroe Wheeler for publication in Manikin.

When she turned to "An Octopus" as a separate poem, Moore already had some usable notes, among them the first lines for the poem. She began her research for a poem about Mt. Rainier by choosing a popular text by the explorer-adventurer Walter Dwight Wilcox, The Rockies of Canada (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1900), copying out quotations and page numbers; and filling nine pages of the stenographer's pad. Then she went over her notes, circling phrases for future use: "roar of ice," "goats looking-glass," "curtain of snow," "At such times you wonder why you came," "while one rested his nerves the other advanced" and many others made familiar by the poem. Next, she turned to other notebooks already filled with quotations from reading and transferred relevant items to the stenographic pad: "glass that will bend," "the cuttlefish concise ... without a shiver." Phrases from the Rules and Regulations: Mount Rainier (Washington D. C.: Department of the Interior, 1922) follow, amid lines moved over from the Wilcox notes. Looking over her notes thus far, she drew a line across the page and wrote "END"; then follow trials and errors culminating in

avalanche

with the crack of a rifle

a curtain of powdered snow

loosed like a waterfall.

Having found the end toward which the poem would move, she took up another book for fresh inspiration for the middle and made five pages of notes from Clifton Johnson's What to See in America (New York: Macmillan, 1919). A few more pages of working over the text and she turned to the development of the beginning of the poem with the idea of "unimagined delicacy" and images of glass. Then her working notes come to an abrupt halt.

III. Additional Notes: A Palimpsest

The trial beginning and end for "An Octopus" found in the notebook appear slightly altered in the final poem and form its outer frame. In the intervening, undocumented period of composition, the poem grew into twenty-eight sentences, a number not to be taken lightly since Moore knew well from her reading that Mt. Rainier is formed by twenty-eight glaciers. Like the mountain itself, this poem is not truly symmetrical but marked by what might be called various elevations. It first presents the whole mountain as seen from a great distance; then it draws the reader close to the base and moves upward to the mountain goat near the peak. Next, it returns to the forest floor to examine its flora, only to ascend again to an orchid above the timberline. At the end, the poem steps back to the long view of the mountain and shows an avalanche that falls from the peak down to the claw of a glacier.

"An Octopus" can be divided into eight sections. The first (11. l-13) describes the octopus of ice compounded by images from land and sea, rock and cephalopod. We see the top of a huge mountain which seems falsely footed in the sea. The second section (11. 14-38) displays fir trees, rocks, and larches: the rock is visible among and above the trees; the fir forests give way, as the eye moves upward, to the "tightly wattled spruce twigs" as the timberline, where the visitor, thinking he has moved forward among the sun-filtering larches, finds himself circling abruptly out of a valley into the cold side of a glacier. Suddenly, there appears a deep lake surrounded by gold and silver, reflecting fir trees subject to gusts of wind. This is the "Goat's mirror" (originally the phrase refers to Lake Agnes in the Canadian Rockies as described by Wilcox) shaped "like the left human foot" (as Wilcox describes Lake Louise), a composite mountain take, as prejudicial of itself as any of those seen at Mount Rainier.

The lake marks the one spot in the mountain of unequaled importance to the wild life in its surrounding parks and forests. Here begins (11. 39-119) the first of two parallel catalogues in the poem. In this one, animals are arranged first in ascending order by habitat: porcupine, beaver, bear, and goat. The goat stands at the top--"a scintillating fragment of those terrible stalagmites"; used to the ice caves, "it stands its ground / on cliffs the color of the clouds . . . / the ermine body on the crystal peak" upon the "antique pedestal of / 'a mountain with those graceful lines which prove it a volcano.’"

The second part of this first catalogue (11. 73-119) remarks upon the distinguishing beauty of "Big Snow Mountain" "of which 'the visitor dare never fully speak at home / for fear of being stoned as an imposter.’" This mountain is home to campers and guides, the chipmunk, the water ouzel, the ptarmigan, the eagle, the badger, and the cayuse ponies. These are the creatures who can approach the goat's summit--if not to live there, at least to climb the mountain and to pause "on some slight observatory."

The "spotted ponies" in their camouflage form a link to the second catalogue (11. 120-154), that of the flowers and trees which hide them. Like the catalogue of animals and birds, that of the plants is arranged in ascending order. The first three items, birch, fern, and lily pad, are found at the forest floor. The next, the avalanche lily, is seen in the upland meadows, the first in spring to push up through the snow and bloom, white on white. All the following flowers bloom in the alpine and subalpine meadows--the two terrains meet on Mt. Rainier at about six thousand feet, just where one walks into Paradise Park above the Inn.

The next group of flowers, leading up to the rhododendron, are a "cavalcade of calico"--red, yellow, white, green—small, repeated spots of color like the printed cotton fabric. Here are the garments of the Western "Calico Ball," the occasion to which women wore printed cotton dresses, contrasted with the "evening clothes" of the American man, invariably black and white like the white rhododendron flower with its leaves transmuted to onyx. Four blue flowers follow--larkspur, pincushion, pea, and lupin, arranged in patches alongside patches of red and white flowers, compared to Persian enamel work. These two groups of flowers, both representative of the mountain meadows, portray two observable phenomena--the parti-colored fields and the patch-colored fields, evident even in present-day postcards of Mt. Rainier's meadows.

The next grouping of flowers leads up to the last and is a composite of hardy plants. The woolly sunflower and the aster survive on what looks like bare rock; the fireweed springs up right after fire decimates a stand of trees; the thistle is hardy at all altitudes.

The final grouping: gentian (blue), ladyslipper (most likely the bird's-foot trefoil, slipper-shaped, known as a ladyslipper, and yellow), harebell (blue) and "mountain dryad" (Moore's transmutation of the "Dryas" from Wilcox, a rosaceous ground cover--white) are all high mountain flowers, culminating in the uppermost and elusive Calypso, "’the goat flower-- / that greenish orchid fond of snow’ / anomalously nourished upon shelving glacial ledges."

Just as the goat stands on the heights of the mountain in the first catalogue, so the Calypso orchid, the goat flower, stands at the top of the second. It is attended by the bluejay who, although fond of "human society or of the crumbs that go with it," "knows no Greek, the pastime of Calypso and Ulysses." Calypso is not only an orchid, of course, but a goddess from the Odyssey, and with her introduction we come face to face with Greeks on Mt. Rainier.

This startling development has the effect of making the reader question what has gone before. So far, the poem has presented only the mountain, its natural inhabitants, its guides and its visitors. To account fully for the presence of the Greeks, we must return to the notebook to see how Moore superimposed references to them upon her notes concerning the natural history of the mountain.

On the train returning from her second trip to the Northwest, Moore again set to work on what was to be her last poem until 1932. She had already separated out of her notes those ideas and phrases which she developed in "Marriage."" A great deal of extra reading and consultation of earlier entries in her reading notebooks went into the poem, and nearly two-thirds of the two hundred and thirty-one lines in the manuscript can be accounted for by various sources. However, here discussion will be limited to those materials which refer to the presence of the Greeks in the alien landscape of Mt. Rainier.

On 21 April 1924, Moore wrote to her brother:

One of the parts of this necessary reading I am doing is very inspiring in which Newman visualizes the material beauties of the Greeks previous to an exposing of spiritual defects.

Her reading was John Henry Newman's Historical Sketches, particularly the passages on "The Site of a University" in which Newman describes Athens and the original grove of "Academe." Moore took Newman's view of the Greeks--philosophers who chose to deify the beautiful, observing propriety as their code of conduct "because it was so noble and so fair"--and used it as an overlay to notes already made from Richard Baxter's The Saints' Everlasting Rest. For example, on page 35 in the notebook she quotes from Baxter the passage (which appears in the poem at lines 182-188) about the definition of happiness as "an accident or a quality, a spiritual substance--the soul itself . . . , such a power as Adam lost & we are still devoid of." She then adds a few words, altering the notes to read:

the Greeks speculating whether it be an accident or a quality, a spiritual substance--the soul itself ..., such a power as Adam lost they had & we are still devoid of.

Here, the speculations of the Christian divine are given to the Greeks with the additional phrase "they had" added, suggesting the Greeks' belief that they were capable of perfect happiness. Further, she had noted from page 114 of Baxter:

Doubtless this will be our lasting admiration

that A[dam] & E[ve] taken by M[ichael] out of E[den],

shld be restored to a dignity greater than they fell from

that such high advancement [with] such long

unfruitfulness & vile rebellion

shd be [the] state of the same persons

that mere farthings [with] infinite advantage shld be

contained in [the] massy gold & jewels of that crown.

Going back over this passage, she circled "such high advancement" and above it wrote "Greeks." This change gives the Greeks "such high advancement" and the same restoration "to a dignity greater than" that from which they or Adam and Eve fell.

On the next page, where her notes from Baxter read:

we speak in such a lazy formal customary strain

[the] piercing melting word becomes

a pearl on lepers hands

weary of a hard heart, some of a proud

some of a passionate & some, of all

these and much, more,

there follows the modification:

the Greeks liked smoothness

telling us of those

upon whose lifelessness

[the] piercing melting word becomes

a pearl on lepers hands

since some of them

weary of a hard heart, some of a proud,

some of a passionate & some, of all

these & much more.

This interjection of "the Greeks liked smoothness" is one of many added to the notes, in each case associating the Greeks with phrases originally without any relationship to them.

Finally, at the end of the Baxter notes, she adds the phrase "like happy souls in Hell" next to an image she discarded: "to have the table not the food is to be richly famished." In the poem, "like happy souls in Hell" is joined to "enjoying mental difficulties" and applied to the Greeks' way of life. Clearly, the phrase is a paradox that the poet associated with the Greeks and with the nonbelievers whom Baxter described as "richly famished."

Moore next moved to the notes taken from W. D. Wilcox's The Rockies of Canada. To his description of Lake Louise as the "goats' looking glass" she added "No Greek would look at the goats' looking glass," no Greek "would have it as a gift." To the image of "blue grottoes hung with icicles . . . At such times you wonder why you came" she added "Siren." From page 74 of Wilcox she noted the Calypso orchid and later superimposed a reference to the Greeks (in the following examples, the italicized words were noted first, the others at a later date):

and genuine & if it were it might sometimes be gross

the Greeks liked smoothness but then--genuine but gross

Calypso a northern orchid named for

the goddess who fell in love w Ulysses

has forgotten--there is no Ulysses merely Mr. D.

And from page 117 of Wilcox we find:

the Greeks liked smoothness

a geographical blank.

The first of these trial statements tests the appropriateness of the phrase "the Greeks liked smoothness" against the orchid and against something "genuine but gross." The second juxtaposes the phrase with "a geographical blank," a reference to the vast areas of the Canadian Rockies which were still unmapped. The finished poem reads: "The Greeks liked smoothness, distrusting what was back / of what could not be clearly seen" (11. 177-178), a statement enhanced by the poet's exploration of the "genuine but gross," a condition perhaps not to be trusted, and of the unmapped mountains which, Wilcox says, troubled even the most intrepid explorers.

In another pair of notebook entries we see the development of the blue jay as Calypso's fitting companion. From Wilcox Moore made notes from a passage where the explorer has unexpectedly come upon a huge wall just when he is running short of rations needed for the energy to climb it:

icehacks no Greek would have it as a gift

raisins & hard tack vs a vertical

wall of rock 500 feet high.

The italicized words were quoted from Wilcox and the others added later. Moore used the phrase "no Greek would have it as a gift" repeatedly in her notes. Here it seems to be associated with the huge wall of rock.

Later in the notebook (p. 65), she combines phrases from several sources:

Pisistratus causing [the] earth to move up & down under

you w hatchet crest & saucy habits

migrating vertically

cruel bold & shy claws like miniature ice-hacks

wise & something of a villain.

Pisistratus, to whom Newman refers as the bringer of culture to Athens, was also the demagogue whose extreme tyranny led to the rise of Greek democracy. He here becomes associated with the blue jay whose description Moore quoted from the guidebook to Mt. Rainier National Park. The notebook entry cited above, in which ice-hacks are placed near something vertical and a Greek or Greeks, is the forerunner of the passage in the poem where the blue jay accompanies the Calypso orchid near the icy peak of the mountain.

What appear to be the last entered notes concerning the Greeks read as follows [the broken lines are Moore's and indicate space left blank for additional phrases]:

END no Greek looks into the goats' lookingglass

Dissatisfied w the ragged marble & the blue gentian & the

the level leisure plain

Calypso the onyx flower forgets

has forgotten that Ulysses was a Greek

The age comes back to mountains

Every spot with its flowers

- - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - -

Now obscured by the avalanche

with the crack of a rifle

a curtain of powdered ice

the legal righteousness of leisure

Before rich motion

the legal righteousness of Greek

Calypso has forgotten that Ulysses was a Greek

Do you think in good sadness

he is here

Calypso the goats flower refuting reproving

olive trees oracles of Greece.The Greeks liked smoothness

and find it difficult to serve us

It is hard to serve when one is trying to be many masters

Inclined to imitate them in their worship

of conformity in heat

a new species of Calypso's hope

upon which lifelessness

the piercing melting word becomes a pearl

on lepers hands.

Here we see the poet intent upon forging an association of the Greeks and her notes from natural history. Her thinking takes her beyond Newman's presentation of the "material beauties of the Greeks" to which she referred in her letter to her brother, to "an exposing of their spiritual defects": "the legal defects"; "the righteousness of Greek"; "their worship of conformity"; their preferring "smoothness" over the rugged and the unknown. It is her superimposition of the Greeks' spiritual defects that shows her method of juxtaposition at work and that can, for instance, account for a blue jay who, as Pisistratus, becomes a suitable companion for the orchid Calypso.

The notes come to an end several stages of composition before the completion of the poem but all intermediate working papers have been lost. Consequently, we must return to the manuscript itself to see the final use Moore made of the material in her notebook. When we take up the poem at line 149, we begin to see how the notes for the end of the poem were expanded and transformed.

We see the blue jay with Calypso, the orchid, at the timberline at the end of the catalogue of flowers and the beginning of the passages about the Greeks. Calypso's "principal companion," the blue jay, does not speak Greek, the language of pride and the triumph of knowledge. The Homeric Calypso and her compatriots enjoyed the mental difficulties of philosophy and the subtle demands of delicate behavior and were not interested in applying these skills to the rough outdoor pleasures of the woods and snows of a setting like Mt. Rainier. They preferred smooth, visible surfaces, sure of their ability to solve problems when they could see the argument. Happiness to them is a philosophical conundrum and unreachable, something we know Adam had and we have not. Of sensitive feelings and hard hearts, they have a wisdom remote from the practical considerations of a game preserve (11. 149-188).

It is self-evident that the inhabitants of the preserve should not have to fear man and that one must follow a regimen to be able to climb the main peak of Mt. Tacoma, the paradoxical fossil. The Greeks, worn out by their love of doing hard things and their love of complexities, had no sympathy for the neatness and accuracy of the glacial mountain (11. 189-212).

At line 211, Moore returns to sea imagery and begins her ending. The "octopus" with its many glacial arms creeps "slowly as with meditated stealth," and is subject to violent winds that tear at its trees. The last six lines make an explosive finale of lightning, snow, and rain, which stimulate an avalanche sounding like "the crack of a rifle" and looking like "a curtain of powdered snow launched like a waterfall." This true-to-life if somewhat frightening imagery returns us to an earlier use of similar imagery (11. 54-72) where the mountain goat stands among "terrible stalagmites" eying a waterfall that looks like "an endless skein swayed by the wind." The goat's "pedestal" is seen to be a volcano whose cone was complete "till an explosion blew it off." Another passage, that concerning Calypso, is related to both the lines about the goat and the ending through imagery which displays the dangers and fearsomeness of the mountain top: the orchid lives "upon shelving glacial ledges / where climbers have not gone or have gone timidly" (11. 150-151); the goat is "'acclimated to grottoes from which issue penetrating draughts / which make you wonder why you came’"; and the avalanche takes place high up the peaks where the "hard mountain" is "planed by ice and polished by the wind." The mountain top, surrounded by magnificent gardens at lower altitude, exemplifies nature's magnificence and power and is accessible only to the daring few.

The poem begins and ends with its narrator at sea level, viewing the octopus from a great distance. Within it are two approaches to the peak. The first, culminating in the presence of the mountain goat, leads us up through trees, rocks, and the habitats of the mountain's fauna. It is the second, the upward-moving examination of the mountain's flora, that calls forth the Greeks, beginning with the appearance of the uppermost flower, the Calypso orchid. As the notebook makes clear, the Greeks are not merely incidental to the poem but a tested and retested element of its composition. From the early stages of the making of the poem, they were being considered for a prominent position near its end. In the final manuscript, they dominate the last third of the text.

IV. The Greeks and Paradise

When we return to the question of the presence of the Greeks on Moore's Mt. Rainier, we find the poet exploring nature and morality in the combined setting of classical and Christian moral philosophy. As we have seen, the notebook and the published notes to the poem both reveal that Moore combined her reading in those subjects with her reading about the natural history of Mt. Rainier and the Canadian Rockies.

In another early notebook, Moore noted that the Athenians "claimed they were themselves the true aboriginal stock and that their fathers were literally sprung from a ‘species of golden grasshopper.’"9 Another notebook, containing her mother's notes and read by the poet, points to the "claim" of the Greeks:

the Athenians didn't

understand themselvesplace a low rate of valuation on themselves--said . . . their ancestors were the golden grasshoppers.10

The crossed-out words are possibly important here, suggesting the idea that the Greeks placed a falsely high valuation on themselves because they "didn't understand themselves."

This notion is reflected in Moore's notes from Newman's Historical Sketches made early in 1924:

so princ[iple] of propriety as substitute for conscience so grasshoppers

the Athenians chose (Propriety) as became so exquisite a people to practice virtue on no inferior considerations, but simply because it was so praiseworthy, so noble & so fair. Not that they discarded law ... but they boasted that "grasshoppers" like them old of race and pure of blood c[ou]ld be influenced in their conduct by nothing short of a fine & delicate taste & sense of honour, & an elevated, aspiring spirit. Their model man was a gentleman.11

Here, the Athenians "boasted" that their conduct could be influenced only by the most high-minded principles. In all three notes, the Athenians--the Greeks--are said to have overstated their case and the suggestion is made that they had built their code of conduct upon a moral philosophy with a shaky first premise, the perfectibility of man. Newman is, of course, imposing his Christian philosophy upon the Greeks. Their basing of goodness and righteousness upon aesthetics--the beautiful is the good--accounts for their "boast." While Newman's position is that of orthodox Christianity, there is an attractiveness to the Greek ideal that certainly interested Moore.

In her notebooks, Moore wrote that elsewhere in Historical Sketches Newman applauds the accomplishments of the Greeks "whose combat was to be with intellectual, not physical difficulties" and who "throve upon mental activity."12 These phrases are reflected in the poem where the Greeks are "not practiced in adapting their intelligence" to the mountaineer's equipment "contrived by those /'alive to the advantage of invigorating pleasures’" but are found "enjoying mental difficulties." He attributes their philosophical deficiencies to their unfortunate--if necessary--failure to discover the Judaeo-Christian system of belief. As we will see, Moore judges the Greeks in her poem a little less harshly than does Newman.

She cites a second Christian moralist as a source for her description of the Greeks: "Emotionally sensitive, their hearts were hard" (1. 189). According to William De Witt Hyde, whose book, The Five Great Philosophies of Life (New York: Macmillan, 1912), describes Epicurean, Stoic, Platonic, Aristotelian, and Christian moral philosophy, Greek conduct is deficient in love. Stoicism, by whose armor one may escape the despair and melancholia which are the logical extensions of the Epicurean pursuit of pleasure, cannot be the final guide to life:

It may be well enough to treat things as indifferent, and work them over into such mental combinations as best serve our rational interests. To treat persons in that way, however, to make them mere pawns in the game which reason plays, is heartless, monstrous.... Again, if its disregard of particulars and individuals is cold and hard, its attempted substitute of abstract, vague universality is a bit absurd. (p. 107)

What is needed, he says, and this is the thesis of his book, is to inform the best of Greek philosophy with Christian love.

In the poem, the behavior of the Greeks is oddly juxtaposed to that of Henry James. While the Greeks are sensitive but hard-hearted in their propriety, Henry James is a master of deepest feeling hidden by his decorum. In describing James, Moore quotes her mother's comment on Carl Van Doren's The American Novel (New York: Macmillan, 1921):

He says what damns James w[ith] the public is his decorum--It isn't his decorum it's his self control, his restraint[,] his ability to do hard things w[ith] suavity. It wears them out.13

In the same notebook, Moore again quotes Mrs. Moore: "The deepest feeling ought to show itself in restraint." Restraint, then, covers for "the deepest feeling" and is not popular with the fiction-reading public. James, in the poem, is a foil to the Greeks. Their "wisdom was remote" from that of the protectors of the mountain; the mountain is "damned for its sacrosanct remoteness" by a public out of sympathy with it, like the public who damned James for his apparent remoteness, his decorum. To extend this line of reasoning, the Greeks are put in the same position as the public; they are out of sympathy with the mountain. In her working notes, Moore makes this dissociation even stronger. "No Greek," she says, "looks into the Goat's looking glass" (the magnificent "Goat's Mirror" lake of 1. 30); "no Greek would have it as a gift."14 The Greeks "liked smoothness and distrusted what was back / of what could not be clearly seen." They would not like the paradoxically named mirror lake where the ripples of the wind "obliterated the shadows of the fir trees" and obscured its glassy surface so that what lay beneath the waves could not be seen. They did not appreciate the forest and they ignored the "invigorating pleasures" of the mountain; they are alien to the American landscape and its rugged beauty. James, in contrast, though an expatriate from that landscape, is described by Moore as "a characteristic American." She notes in an essay that he himself recognized "the importance to his writing of his American upbringing and point of view." His "restraint" masks an abundance of affection. As she wrote, "there was in him 'the rapture of observation,' but more unequivocally even than that, affection for family and country.... Henry James's warmth is clearly of our doting variety."15 His "restraint" is like that of the mountain and suits it as the Greeks' hardness of heart does not.

"Calypso, the goat flower" which introduces the Greeks into the poem is the delicate white orchid whose name means "hidden." It blooms white on white amid the snows of early spring. In her mythic character, Calypso is the goddess who detained Ulysses for seven years on her island, offering him immortality if he would remain with her. However, she obeyed Zeus's order to provide Ulysses with an axe and tools to make a raft of tree limbs, and she watched him set sail again toward Ithaca: "Bows, arrows, oars and paddles for which trees provide the wood" (1. 171).

In the poem, the flower is called Calypso and when the Greek language is mentioned, it is recalled that the goddess and Ulysses passed their time speaking in that tongue. In the notebook, Calypso stands in opposition to the Greeks:

Calypso has forgotten that Ulysses was a Greek

Calypso the goats flower

affirming in good sadness that Ulysses is not here . . .. . . .

Calypso the goats flower refuting

oracles of Greece to speak of

how we tend in N America to rough it. . . .

advocating an idealism like Calypso's hope

Here Calypso refutes Grecian oracles on behalf of North America and those who tend to "rough it." The Calypso flower is a North American native with a Grecian name; in the poem, she is companion to the blue jay who "knows no Greek," she lives among the "odd oracles" of the gamewardens, and is "the goat's flower"--an epithet purely of Marianne Moore's making--and ally of the mountain goat.

Both Calypso and the mountain goat are white and set against the snows of the upper alpine regions of the mountain. Calypso appears tinged with green like the mountain itself (cf. 1. 13); the goat is trimmed with black without which he, like Calypso without the green, would be invisible against the "cliffs the color of the clouds/ . . . the ermine body on the crystal peak." Both the goat and the goat-flower have godlike abilities to survive an environment threatening to other beings.

The suggestion of Pan is inevitable when goats and Greeks are mentioned in the same place. Pan, the goat-god of pasture and forest, the symbol of fertility and the ability to enchant all nature with his pipe, is the only Greek god allowed in the Garden of Eden in Paradise Lost. Milton's description of the garden was known to Moore from childhood and studied at college. It is not surprising to find it echoed in her poem:

. . . and over head up grew

Insuperable highth of loftiest shade,

Cedar, and Pine, and Fir, and branching Palm,

. . . .

And higher than that Wall a circling row

Of goodliest Trees loaded with fairest Fruit,

Blossoms and Fruits at once of golden hue,

Appear'd, with gay enamel'd colors mixt:

. . . .

God had thrown

That Mountain as his Garden mould, high rais'd

Upon the rapid current, which through veils

Of porous Earth with kindly thirst up-drawn

Rose a fresh Fountain, and with many a rill

Water'd the Garden;

. . . .

But rather to tell how, if Art could tell,.

How from that Sapphire Fount the crisped Brooks,

Rolling on Orient Pearl and sands of Gold,

With mazy error under pendant shades

Ran Nectar, visiting each plant, and fed

Flow'rs worthy of Paradise, which not nice Art

In Beds and curious Knots, but Nature boon

Pour'd forth profuse on Hill and Dale and Plain,

. . . .

Another side, umbrageous Grots and Caves

Of cool recess, . . . meanwhile murmuring waters fall

Down the slope hills, disperst, or in a Lake,

That to the fringed Bank with Myrtle crown'd

Her crystal mirror holds, unite thir streams.

The Birds thir choir apply; airs, vernal airs,

Breathing the smell of field and grove, attune

The trembling leaves, while Universal Pan,

Knit with the Graces and the Hours in dance

Led on th' Eternal Spring.

(Book IV, 138-268)16

Milton's paradise is a garden on a mountain with blossoms of "gay enamel'd color," "rapid current," sapphires, gold, rich trees, "Grots and Caves / of cool recess," waterfalls, and a lake holding "Her crystal mirror." Moore's earthly paradise bears a dramatic resemblance to Milton's. In her poem are flowers in "an arrangement of colors / as in Persian designs of hard stones with enamel" (11. 134-135); "rapids and high pressured falls" (1. 85); "sapphires in the pavement of the glistening plateau" (1. 144); "dumps of gold ... ore" (1. 30); "grottoes from which issue penetrating draughts" (1. 61); a "waterfall which never seems to fall" (1. 57); and the lake, "The Goat's Mirror."

The mountain goat, for whom the lake is named, has a role in "An Octopus" like that of Pan in Paradise Lost. Pan dances with the Graces and leads on the "eternal spring." The mountain goat's distinguishing characteristic is that he is light on his feet--in contrast with his bulky torso--and one of the signs of spring is his ascent to the upper regions of the mountain. His preeminent position in the first half of the poem suggests his importance to it. And when we associate the mountain goat with the god Pan we find that Moore's paradise and Milton's both allow the Greeks to be present through the goat-god while at the same time confronting the flaw of their philosophy, the preference of intellect over love.

Milton's Pan is in the midst of the Judaeo-Christian myth, in paradise before Adam and Eve fell to Satan's temptation. To test man's love, God exacted of him only one act of obedience: not to eat the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. Satan's ruse was to "excite their minds / With more desire to know" (IV, 522-23) and so tempt them to disobey God's order. Satan, of course, succeeds, and man is banned from the garden with only the promise of ultimate deliverance "by the Woman's Seed." The message of Satan's trickery is plainly that loving obedience is difficult for man, even in paradise, and all too easily overcome by the desire for knowledge reserved to God. Such knowledge is dangerous; for man to seek it is to fall from paradise.

In Paradise Regained, Milton confronts the question of whether the great learning and culture of the Greeks, having taken place after the fall of Adam and before the redemption of Christ, have merit in a Christian world. In Book IV, Satan subjects the Son of God, the one born of the Woman's Seed, to a last temptation. He takes Christ up to a high mountain and shows him "Athens, the eye of Greece, mother of arts / And eloquence," the "grove of Academe," and all the wonders of the Greek world with its teachers of "moral prudence" and its oracles. He tempts the Savior with the kingship of this great empire, but the Savior rejects him, saying:

Much of the Soul they talk, but all awry,

And in themselves seek virtue, and to themselves

All glory arrogate, to God give none,

Rather accuse him under usual names,

Fortune and Fate, as one regardless quite

Of mortal things. Who therefore seeks in these

True wisdom, finds her not, or by delusion

Far worse, her false resemblance only meets,

An empty cloud. However, many books,

Wise men have said are wearisome; who reads

Incessantly, and to his reading brings not

A spirit and judgment equal or superior

(And what he brings, what needs he elsewhere seek)

Uncertain and unsettl'd still remains,

Deep verst in books and shallow in himself,

Crude or intoxicate, collecting toys,

And trifles for choice matters, worth a sponge;

As Children gathering pebbles on the shore.

(IV, 313-330)

Milton here accuses the Greeks of a failure of love: they were content to "in themselves seek virtue, and to themselves / All glory arrogate, to God give none"; and a failure of intellect: they sought knowledge without spirit and judgment. Milton has Christ scorn the Greeks for not having found and followed the God of Abraham. Moore does not pass such harsh judgment in her poem, seeing the Greeks' "delicate behavior," "'so noble and so fair,’" not as scornful but as flawed. She lauds their intellectual prowess and emotional sensitivity but she sees the same failure of love that Milton found in them and in Adam: lack of trust in what they could not understand and hardness of heart. Because of these flaws, the Greeks do not adapt their intelligence to a setting like Mt. Rainier (1. 167); they do not find stimulation of "moral vigor" in the forest (11. 175-176); they have only a wisdom "remote / from that of these odd oracles" of the mountain or in its natural paradise.

The Greeks "like happy souls in Hell" are found on another mountain, in The Divine Comedy. The shape of Dante's Purgatory is interestingly like that of Mt. Rainier. The mountain of Purgatory itself was formed on the surface of the earth by volcanic action resulting from Satan's being hurled into the fiery center of the sphere. At its top is the terrestrial paradise described in the Purgatorio's Cantos XXVIII-XXXIII, the prelapsarian garden of Eden in a post-lapsarian context.17 To this paradise, in Dante's terms, the Greeks aspired, knowing no other. As Matilda, Dante's first guide among the flowery paths of the garden, reassured Dante:

They who in olden times sang of the Golden Age and its happy

state, perchance dreamed in Parnassus of this place.(Purgatorio, XXVIII, 136-141)

Dante places Homer, the other Greek poets, and the philosophers in the first circle of the Inferno--Limbo--where their only suffering is that they live with the desire and without the hope of seeing God. Virgil tells Dante that after passing through the Inferno, he will ascend to Purgatory where he will find souls who, unlike the "heathens," can be cleansed and seek Paradise:

And then you will see those who are happy in the fires of hell, for they hope to come, whenever the time shall be, among the blessed.

(Inferno, I, 118-120.)

Marianne Moore in effect moves the Greeks from the Inferno to the Purgatorio by applying to them the phrase "like happy souls in hell" (1. 162). Dante's Limbo was a place without hope from which Christ liberated only Abraham and the worthy Israelites. Moore elevates the Greeks to the place of those who were undergoing purification before being allowed to enter heaven. Why? Orthodox Christian theology insists that the unbaptized pagans who led the best lives they could, will upon death, enter Limbo, but at the last day, the "end of the world," they will, through the redemption of Christ, enter heaven. To Moore, the Greeks' failure was like that of Adam: the choice of knowledge over love. Like Adam, they could not live in Paradise. And like him, too, they could be purified and redeemed.

"An Octopus" is not a Christian tract but it does refer obliquely to elements of Christian moral philosophy to make its point. The Calypso orchid and the mountain goat upon the mountain's peaks suggest their Greek counterparts who in turn recall the splendid but flawed culture of Greece, an alien idealism set in contrast to the realism of the mountain and its inhabitants. Like the Garden of Eden, whether of Genesis, Milton, or Dante, Mt. Rainier excludes from its precincts those "disobedient persons" but it does allow them to return with "permission in writing." This natural paradise is a microcosm of the Western world and its history: a complete, magnificent mountain, a preserved national park, but subject to the flaws of men who might abuse it. The poem keeps close to the natural history--earlier called natural philosophy--of the mountain. The introduction of the Greeks forces the reader beyond the breathtaking experience of the mountain to a reflection upon the meaning of human life, the forces of nature, and his own beliefs.

These remarks bring up more issues than they settle. They lead us to want to query Moore's metaphysics, her position on Christian orthodoxy, the extent of her use of irony in the poem. "An Octopus" is a profound expression of her world view, but it is a baffling one. These first notes only begin the elucidation.

When visitors to Mt. Rainier turn back down the track toward Tacoma, Seattle, and American civilization, they move west toward the end of the continent, toward Puget Sound and the Pacific Ocean. After her trip to the mountain, Moore went to spend two summers at Bremerton, between the Sound and the Pacific. She saw the mountain "out" some of the time, a reminder from afar of its grandeur and her visit to Paradise Park. Much of the time it was invisible, a challenge to a poet with "a burning desire to be explicit" about the magnificence of nature.

NOTES

1

All manuscript material referred to here (unless otherwise noted) is held by the Marianne Moore Collection, Rosenbach Museum and Library, Philadelphia. All previously unpublished material by Marianne Moore is used with the permission of Clive E. Driver, Literary Executor of the Estate of Marianne C. Moore. The dates of the Moores' two trips are established from family letters and appointment books.2

Marianne Moore submitted a MS of "An Octopus" to The Dial on 22 September 1924. This copy is at the Beinecke Library, Yale University. A carbon copy of the MS is at the Rosenbach.3

These photographs survive in a postcard album at the Rosenbach. They were produced for the Canadian Pacific Railroad and were sold at newsstands along the route.4

A. L. S., Marianne Moore to John Warner Moore, 12 July 1923.5

A. L. S., John Warner Moore to Mrs. Moore and Marianne, 29 January 1922.6 These names are also used in family letters during this period.

7

Rosenbach 1251/17. This notebook is a ruled stenographer’s notebook that Moore used to draft poems and to make notes from books she read to gather information for poems. It is evident from different layers of regular and colored pencil that the notes themselves were worked over and revised at different times. The chronology of notes concerning "An Octopus" is as follows: 1) notes for the single poem that became "Marriage" and "An Octopus"; 2) notes from Richard Baxter (his book and the others cited briefly here are cited fully in the text); 3) notes entitled "An Octopus" and taken from W. D. Wilcox; 4) notes dated 23 October 1924, begun on the train home during the second journey; 5) notes from Johnston; 6) notes from a guidebook to Mt. Rainier; 7) overlay of phrases concerning the Greeks made upon all the preceding notes, presumably after 21 April 1924 when she read Newman.8

In the notebook, the drafts of two poems follow those of "Marriage" and "An Octopus," but the first, "Sea Unicorns and Land Unicorns," was published in The Dial in October, 1924, and the second, "Silence," in November, 1924, preceding publication of "An Octopus" in December. The two-month lead-time of The Dial required that the poems published earlier were finished and submitted by August and September, respectively.9

Rosenbach 1250/l/43.10

Rosenbach 1250/18.11

Rosenbach 1250/5/26.12

Rosenbach 1250/24/11.13

Quoted in Rosenbach 1250/26/51.14

Rosenbach 1251/17/54.15

See "Henry James as a Characteristic American," A Marianne Moore Reader (New York: Viking, 1961), pp. 130-138. This article was originally published in 1934.16

The Complete Poetical Works of John Milton, ed. Douglas Bush (Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 1965).17

The Purgatorio of Dante Alighieri, ed. Israel Gollancz (London: J. M. Dent, 1906).From Twentieth Century Literature 30.2-3 (Summer Fall 1984): 242-266.

Taffy Martin

As if to counter the dismal effect of "Marriage," Moore follows the shock of her conclusion with another long, dense poem, "An Octopus," which begins somewhat ominously and quickly turns that mood into joyful appreciation of the indecipherable density of Mount Tacoma's glacier. Every specimen of disarray offers a form of delight, precisely because of its inherent and unfathomable contradiction. A visitor to the glacier finds that its density of growth makes vision difficult, even misleading; but he enjoys the opacity, which he finds

under the polite needles of the larches

"hung to filter, not to intercept the sunlight"—

met by tightly wattled spruce-twigs

"conformed to an edge like clipped cypress

as if no branch could penetrate the cold beyond its company"

It is thus contrarily pleasant to discover that "Completing a circle, / you have been deceived into thinking that you have progressed." The confusion "prejudices you in favor of itself." Throughout the poem, Moore holds in suspension and demonstrates the simultaneous presence of the two opposing qualities of the glacier. Although "damned for its sacrosanct remoteness," it attracts those who damn that remoteness while engaged in attempts to "'conquer the main peak of Mount Tacoma.’" Nevertheless, combined with that remoteness, "Relentless accuracy is the nature of this octopus / with its capacity for fact." Offering partial shelter, the mountain "receives one under winds that 'tear the snow to bits / and hurl it like a sandblast / shearing off twigs and loose bark from the trees.'" It also challenges its visitors' perceptions, producing questions such as this one.

Is "tree" the word for these things

"flat on the ground like vines"?

some "bent in a half circle with branches on one side

suggesting dust-brushes, not trees;

some finding strength in union, forming little stunted groves

their flattened mats of branches shrunk in trying to escape"

from the hard mountain "planed by ice and polished by the wind"--

The poem ends with an explosion of motion that finds mysterious calm and self-possession on the mountain, even in the midst of unpredictable violence. The "symmetrically-pointed" octopus survives the violence of an avalanche because of its "curtain of powdered snow launched like a waterfall." Moore wants us, in the words of another poem of impossible opposites, to "believe it / despite reason to think not."

From Marianne Moore: Subversive Modernist. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1986. Copyright 1986 by U of Texas Press.

Margaret Dickie

Her sensitivity to detail might suggest an interest only in surfaces, but she had a clear sense of the limits of detail and an awareness that not all external marks could be so clearly seen. In "An Octopus," for example, which moves through eight pages toward the compliment that "Relentless accuracy is the nature of this octopus / with its capacity for fact," Moore was more interested in capaciousness than in accuracy. Over and over, she insisted that there is no way to accurately measure the twenty-eight ice fields she detailed. At the start, the "octopus" is described as "deceptively reserved and flat"; "Completing a circle" around it, she claimed, "you have been deceived into thinking you have progressed."

The "octopus" is unapproachable, a place where all our observational skills are unreliable and even water is "immune to force of gravity in the perspective of the peaks." Spotted ponies, "hard to discern," fungi "magnified in profile," inhabit a landscape that is tricky, changeable, and impossible to accurately fix in view. She pictured the octopus-glacier "'creeping slowly as with meditated stealth, / its arms seeming to approach from all directions.’"

Here is no "deliberate wide-eyed wistfulness'" in the description of nature but rather a constant iteration of the impossibility of "relentless accuracy" in seeing and capturing anything in language, although she refused to resolve "'complexities which still will be complexities / as long as the world lasts.'" "An Octopus" is a view of the inscrutability of nature imagined by a woman and as a woman. The glacier is "of unimagined delicacy," "it hovers forward 'spider fashion / on its arms' misleadingly like lace." It is "distinguished by a beauty / of which 'the visitor dare never fully speak at home,’" "odd oracles of cool official sarcasm," which nonetheless differ from the wisdom of those "'emotionally sensitive'" whose hearts are hard.

Hovering forward with arms approaching from all sides, this imagined glacier would appear to be the very image of the engulfing mother, yet unlike Whitman’s old crone out of the sea this feminized landscape is imagined not so much as personally threatening but as stalwartly resistant. Its mysteries are those of "doing hard things," of endurance, of unimaginable resistance to the poet's imaginative grasp. They are mysteries appreciated and confirmed here by this woman poet who imitated them.

From The Columbia History of American Poetry. Ed. Jay Parini. New York: Columbia UP, 1993. Copyright © 1993 by Columbia UP.

Lynn Keller

[Comparing Moore’s "An Octopus" and Elizabeth Bishop’s "Florida"]

Like journalists, the speakers of "Florida" and "An Octopus" do not reflect upon themselves or their relation to the landscape, but focus on providing information--not the comprehensive or "useful" knowledge one might acquire from an encyclopedia, but those remarkable facts likely to awaken in readers a sense of wonder. In both poems the narrator is present as a lively but impersonal reporting voice.

Nonetheless, the poems' opening lines also hint of significant differences between the two artists' sensibilities. In "Florida" Bishop immediately draws attention to the aesthetic character of her subject and suggests a personal attachment; it is "the state with the prettiest name." Moore's fascination with the glacier that is her subject in "An Octopus" derives from a more intellectual interest in its physical characteristics; in her opening lines she notes the remarkable thickness of the ice fields and the anomalous flexibility of that ice. As is her common practice, Moore emphasizes the prosaic character of her subject by employing scientific jargon and quoting from unlyrical "business documents and / / schoolbooks"--in this case, the "Department of Interior Rules and Regulations" and "The National Parks Portfolio." In "Florida" Bishop follows Moore's example of including facts or statistics, informing us that enormous turtles leave "large white skulls with round eye-sockets / twice the size of a man's" and that the alligator "has five distinct calls: / friendliness, love, mating, war, and a warning." She thereby achieves a Moore-like impression of reportorial accuracy and specificity, but both the facts and the manner in which she presents them are more conventionally poetic and more emotionally suggestive than Moore's. Humans are ominously dwarfed in Bishop's fierce and death-littered landscape.

In order to impress upon us that they are reliable witnesses and guides, Bishop and Moore in their descriptive passages insist on careful discriminations. For example, the opening lines of "Florida" record the distinction between the appearance of mangrove roots when living and their appearance when dead:

The state with the prettiest name,

the state that floats in brackish water,

held together by mangrove roots

that bear while living oysters in clusters,

and when dead strew white swamps with skeletons,

dotted as if bombarded, with green hummocks

like ancient cannon-balls sprouting grass.