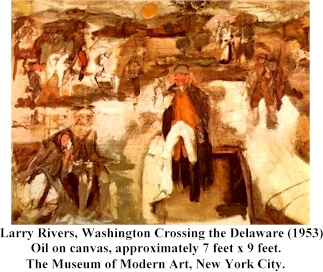

On "On Seeing Larry Rivers' Washington Crossing the Delaware . . . ."

Brad Gooch

O'Hara and Rivers were both

obsessed that season with the Russians. O'Hara's obsession was with Mayakovsky, who had so

stridently declared that "The poet himself is the theme of his poetry" and

"The city must take the place of nature," and from whom O'Hara had picked up

what James Schuyler has described as "the intimate yell." (In a nasty swipe of a

poem, "Answer to Voznesensky & Evtushenko," in 1963 O'Hara accused the

Soviet poets of being "Mayakovsky's hat worn by a horse.") Rivers was busily

reading War and Peace, about which John Myers grudgingly asked in a memoir:

"And who got him to read War and Peace? Not Frank." Between

Mayakovsky's "The Cloud in Trousers," O'Hara's "Second Avenue" and

Tolstoy's War and Peace, the epic was in the air. So Rivers decided to make his own

attempt at a large scale epic painting, George Washington Crossing the Delaware, which

he has described as "like getting into the ring with Tolstoy." It was based on

the original work by the nineteenth-century academic painter Emmanuel Leutze, a

German-American sentimental realist known for the stage-set heroics in this tableau as

well as in his mural decorations for the Capitol. O'Hara found the notion of updating this

historic figure "hopelessly corny" until he saw the painting finished, his

coming around later recorded in his 1955 poem "On Seeing Larry Rivers' Washington

Crossing the Delaware at the Museum of Modern Art." Among the painters, however,

the work--with its parodistic figure drawing--was a battle cry, thumbing its nose at

Abstract Expressionism and pointing the way toward what would later become Pop Art. It was

also quite revolutionary in dispensing with the lush brushwork of de Kooning in favor of

thin, soaked washes. Rivers was sneered at in the Cedar, where Gandy Brodie, an abstract

painter who had studied dance with Martha Graham, described him as a "phony" and

one persnickety woman painter dubbed the new canvas Pascin Crossing the Delaware. The

painting was a breakthrough for Rivers in finding his own breathing space in the

increasingly claustrophobic crowd of young painters.

O'Hara and Rivers were both

obsessed that season with the Russians. O'Hara's obsession was with Mayakovsky, who had so

stridently declared that "The poet himself is the theme of his poetry" and

"The city must take the place of nature," and from whom O'Hara had picked up

what James Schuyler has described as "the intimate yell." (In a nasty swipe of a

poem, "Answer to Voznesensky & Evtushenko," in 1963 O'Hara accused the

Soviet poets of being "Mayakovsky's hat worn by a horse.") Rivers was busily

reading War and Peace, about which John Myers grudgingly asked in a memoir:

"And who got him to read War and Peace? Not Frank." Between

Mayakovsky's "The Cloud in Trousers," O'Hara's "Second Avenue" and

Tolstoy's War and Peace, the epic was in the air. So Rivers decided to make his own

attempt at a large scale epic painting, George Washington Crossing the Delaware, which

he has described as "like getting into the ring with Tolstoy." It was based on

the original work by the nineteenth-century academic painter Emmanuel Leutze, a

German-American sentimental realist known for the stage-set heroics in this tableau as

well as in his mural decorations for the Capitol. O'Hara found the notion of updating this

historic figure "hopelessly corny" until he saw the painting finished, his

coming around later recorded in his 1955 poem "On Seeing Larry Rivers' Washington

Crossing the Delaware at the Museum of Modern Art." Among the painters, however,

the work--with its parodistic figure drawing--was a battle cry, thumbing its nose at

Abstract Expressionism and pointing the way toward what would later become Pop Art. It was

also quite revolutionary in dispensing with the lush brushwork of de Kooning in favor of

thin, soaked washes. Rivers was sneered at in the Cedar, where Gandy Brodie, an abstract

painter who had studied dance with Martha Graham, described him as a "phony" and

one persnickety woman painter dubbed the new canvas Pascin Crossing the Delaware. The

painting was a breakthrough for Rivers in finding his own breathing space in the

increasingly claustrophobic crowd of young painters.

Meanwhile his relationship with O'Hara was becoming more difficult. O'Hara was making demands that Rivers felt were unreasonable. "He thought he wasn't putting pressure on me but he actually was," remembers Rivers of O'Hara's wanting to go home with him after a party "Like we'd be somewhere and I'd be enjoying myself. And he says, "Well, are we going?' Like meaning, 'Well is anything going to happen?' I wasn't in love in that sense."

From City Poet: The Life and Times of Frank O’Hara. Copyright © 1993 by Brad Gooch.

Marjorie Perloff

In certain cases, when O'Hara worked very closely with a particular painter, the poem absorbed the spirit of the painting thoroughly enough to become independent. This is true, I think, of "On Seeing Larry Rivers' Washington Crossing The Delaware at the Museum of Modern Art." Rivers explains what he was trying to do in this particular painting in an interview with O'Hara for Horizon (1959):

... what could be dopier than a painting dedicated to a national cliché--Washington Crossing the Delaware. The last painting that dealt with George and the rebels is hanging in the Met and was painted by a coarse German nineteenth-century academician who really loved Napoleon more than anyone and thought crossing a river on a late December afternoon was just another excuse for a general to assume a heroic, slightly tragic pose.... What I saw in the crossing was quite different. I saw the moment as nerve-wracking and uncomfortable. I couldn't picture anyone getting into a chilly river around Christmas time with anything resembling hand-on-chest heroics.

"What was the reaction when George was shown?" O'Hara asks. "About the same reaction," Rivers replies, "as when the Dadaists introduced a toilet seat as a piece of sculpture in a Dada show in Zurich. Except that the public wasn't upset--the painters were. One painter, Gandy Brodie, who was quite forceful, called me a phony. In the bar where I can usually be found, a lot of painters laughed."

O'Hara himself, however, understood the Rivers painting perfectly. His poem, written in 1955, treats Washington's Crossing of the Delaware with similar irreverence and amused contempt:

Now that our hero has come back to us

in his white pants and we know his nose

trembling like a flag under fire,

we see the calm cold river is supporting

our forces, the beautiful history.

The next four stanzas continue to stress the absurdity of what O'Hara, like Rivers, presumably regards as a nonevent, the "crossing by water in winter to a shore / other than that the bridge reaches for." Here the silly rhyme underscores the bathos of what is meant by our "beautiful history" (note that the crossing takes place in a "misty glare"); and the poem ends with a satiric address to George, culminating in the pun on "general":

Don't shoot until, the white of freedom glinting

on your gun barrel, you see the general fear.

Although O'Hara's poem is especially witty if read in conjunction with Rivers's painting, it can be read quite independently as a pastiche on a Major Event in American History, an ironic vision of the "Dear father of our country," with "his nose / trembling like a flag under fire."

O'Hara's poetic response to the painting of Larry Rivers, like his lyric celebrations of Grace Hartigan, suggests that he was really more at home with painting that retains at least some figuration than with pure abstraction.

From Frank O’Hara: Poet Among Painters. Copyright © 1977 by Marjorie Perloff.

David Lehman

It is a paradox worth savoring that the painters closest in mood and temperament to the New York poets were not the makers of the abstract revolution but such "second generation" figures as Larry Rivers, Jane Freilicher, and Fairheld Porter, not one of them an abstract artist. To understand how the New York School of poets assimilated the influence of their painterly namesakes, we might linger for a moment over the differing ways in which a Rivers or a Porter responded to the avant-garde imperatives of the day. The example of Rivers was particularly crucial for O'Hara and Koch. Porter's example had a corresponding importance for Schuyler and Ashbery.

Born Yitzroch Grossberg in the Bronx, Rivers was an uninhibited, grass-smoking, sex-obsessed jazz saxophonist in his early twenties when he took up painting in 1945. His Bonnard-inspired early works made Clement Greenberg sit up and take notice. Though he would later modify his praise and then with- draw it altogether, Greenberg declared in 1949 that Rivers was already "a better composer of pictures than was Bonnard himself in many instances"—and this on the basis of Rivers's first one- man show. Rivers—who can, as I write this, still be heard playing the saxophone at the Knickerbocker Bar in New York City some Sunday nights—always retained the improvisatory ideal of jazz. The make-it-up-as-you-go-along approach is evident in even his most monumental constructions—such as The History of the Russian Revotution (1965) in Washington's Hirshhorn Museum— which have a fresh air of spontaneity about them, as if they had just been assembled a few minutes ago.

Rivers relied on "charcoal drawing and rag wiping" for the deliberately unfinished look of his pictures. Also distinctive was his prankish sense of humor. In 1964 he painted a spoof of Jacques-Louis David's famous Napoleon in His Study (1812), the portrait of the emperor in the classic hand-in-jacket pose. Rivers's version, full of smudges and erasures, manages to be iconoclastic and idolatrous at once. The finishing touch is the painting's title: Rivers called it The Greatest Homosexual. A visitor to Rivers's Fourteenth Street studio in 1994, seeing a picture on the wall with the Napoleon motif in it, asked him why he had given the original painting its unusual title. "In those days I was carrying on with people in the gay bathhouse world," Rivers said. "Napoleon's pose was like, 'Get her!' Also, it was a kind of joke, since the art world at the time was primarily homosexual. And I had just read that Napoleon was a little peculiar. In St. Helena he used to be surrounded by an entourage of officers and he would take a bath in front of them, nude."

There is a strand of Rivers's work that can only be understood if you take into account the homosexual aestheticism that he found embodied in the poems and person of O'Hara. In the early 1950s, "queerdom was a country in which there was more fun," Rivers has said. "There was something about homosexuality that seemed too much, too gorgeous, too ripe. I later came to realize that there was something marvelous about it because it seemed to be pushing everything to its fullest point."

If one condition of avant-garde art is that it is ahead of its time, and another is that it proceeds from a maverick impulse and a contrary disposition, Rivers's vanguard status was assured from the moment when, in open apostasy, he audaciously made representational paintings. glorifying nostalgia and sentiment, while undercutting them with metropolitan irony. His paintings of brand labels, found objects, and pop icons—Camel cigarettes, Dutch Masters cigars, the menu at the Cedar Tavern in 1959,a French hundred-franc note—preceded Pop Art but eluded the limitations of that movement. And his pastiches of famous paintings of the past—such as his irreverent rendition of Emmanuel Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware (1953)—anticipated the breezy ironies of postmodernism without forfeiting the painterly touches of Abstract Expressionism. The painting, Rivers told O’Hara, "was just a way for me to stick my thumb out at other people. I suddenly carved a little corner for myself. Luckily for me I didn’t give a crap about what was going on at the time in New York painting. In fact, I was energetic and egomaniacal and, what is even more important, cocky and angry enough to want to do something that no one in the New York art world could doubt was disgusting, dead, and absurd. So, what could be dopier than a painting dedicated to a national cliché?"

Rivers denied that his Washington Crossing the Delaware was specifically a parody of Emmanuel Leutze’s painting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He maintained that his true inspiration derived from the patriotic grade school plays he had acted in or watched as a boy. This explanation made the picture no less heretical in an art world that had given up on representation and was bound to consider a patriotic theme as either hopelessly corny or retrograde. But for Rivers’s poet friends, the painting- -which the Museum of Modern Art purchased in 1955—was an electric charge. Kenneth Koch wrote a play, George Washington Crossing the Delaware, in which the father of our country is glorified with ironic hyperbole. And Frank O'Hara. in his poem "On Seeing Larry Rivers.s Washington Crossing the Delaware at the Museum of Modern Art," used the opportunity to state a "revolutionary" credo:

To be more revolutionary than a nun

is our desire, to be secular and intimate

as, when sighting a redcoat, you smile

and pull the trigger.

It is conceivable that the "redcoat" O'Hara envisioned here coat of red paint. The gun in Rivers's hands, or in his own, the promise of freedom from dogma or domination:

Don't shoot until, the white of freedom glinting

on your gun barrel, you see the general fear.from The Last Avant-Garde: The Making of the New York School of Poets. Copyright © 1998 by Doubleday, Inc.

Hazel Smith

While some of O'Hara's poems are more pop camp and others more abstract, poems like 'Rhapsody' (O'Hara 1977a, p. 325) combine the two. This mixture of Pop Camp and Abstract Expressionism is also to be found in the work of Larry Rivers. Rivers worked on the edges of the New York School of painters who included Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, Alfred Leslie, Michael Goldberg, Norman Bluhm and Jane Freilicher. The close relationship between Rivers and O'Hara, and the way in which Rivers's work—like O'Hara's—combines abstract and representational modes, has already been well discussed by Marjorie Perloff (Perloff 1979). I want to argue that Rivers's work is in a similar relationship of 'complementary antagonism' to Abstract Expressionism and Pop Camp as O'Hara's. Rivers often used commercial images in his painting and was an important forerunner of Pop Art. However, like O'Hara, Rivers's work deviated from Pop Art. Hefen Harrison argues that Rivers differs from Pop Art, which 'comments on the social implications of standardization, mass dissemination of information, and the dehumanizing effects of modern culture'. What Rivers does have in common with the Pop Artists, Harrison argues, is to employ 'traditionally unacceptable raw material' (Harrison 1984, p. 48). Similarly, Libby suggests that 'While pop art flattens . . . Rivers discovers the radiance of ordinary things, imaginatively transforming them in ways that Williams would admire but Warhol might consider perversely romantic' (Libby 1990, p.134). Although these comparisons make a useful distinction, again they tend to underestimate the aestheticisation of the image within Pop Art.

In fact, 'pop camp' is also an important ingredient of Rivers's work, and this is shown not only in his inclusion of consumer goods but also in his parodic revisions of historical representations which are deeply ingrained in American popular culture. A good example of this kind of work is 'Washington Crossing the Delaware' (1953), an important 'repainting' of a traditional American icon, Leutze's painting of 'Washington Crossing The Delaware', which undermined the heroism, masculinity and patriotism of the original. The painting appeared the year after the Leutze was in the public eye in the celebrations for the 175th anniversary of the river crossing. At that time the Cold War and McCarthyism were at their height, and patriotism had become a national obsession. Rivers's painting undercuts the heroic Napoleonic stance of Washington in the Leutze and humanises it. Washington becomes only one of many going about their business; he seems isolated and his stance is much less heroic and purposeful than in the original. While seeming to buy into the sentiments of nationalism and patriotism, Rivers subverts them by taking Washington off his heroic pedestal. Rivers said of the painting:

The last painting that dealt with George and the rebels is hanging at the Met and was painted by a coarse German nineteenth-century academician who really loved Napoleon more than anyone and thought crossing a river on a late December afternoon was just another excuse for a general to assume a heroic, slightly tragic pose . . . What could have inspired him I’ll never know. What I saw in the crossing was quite different. I saw the moment as nerve-wracking and uncomfortable. I couldn't picture anyone getting into a chilly river around Christmas time with anything resembling hand-on-chest heroics. (Davidson 1983, p. 74).

Conflicting readings, however, inhabit the painting, and it seems to be more ambiguous than critics sometimes allow. Does Washington really look as 'uncertain' as critics say? The deconstruction is all the more effective because the attitudes which are being questioned still have a presence within the painting, in the same way that they do within O'Hara's poems.

O'Hara responded to the painting with the poem, 'On Seeing Larry Rivers' Washington Crossing the Delaware at the Museum of Modern Art'. This poem characterises Washington as afraid, gun-happy and a liar. He is the father of debatable notions about freedom which honour individualism rather than community. 'See how free we are! as a nation of persons.' In other words, the poem narrativises the painting further, implying, but not determining, trajectories of plot, character and past history.

from Hyperscapes in the Poetry of Frank O'Hara: Difference/Homosexuality/Topography. Liverpool UP, 2000. Copyright © 2000 by Hazel Smith.

Return to Frank O'Hara