On "Ballad of Birmingham"

R. Baxter Miller

In 1962 Randall became interested in Boone House, a black cultural center which had been founded by Margaret Danner in Detroit. Every Sunday Randall and Danner would read their own work to audiences at Boone House. Over the years the two authors collected a group of poems which became the first major publication of Broadside Press, Poem Counterpoem (1966).

Perhaps the first of its kind, the volume contains ten poems each by Danner and Randall. The poems are alternated to form a kind of double commentary on the subjects they address in common. Replete with allusions to social and intellectual history, the verses stress nurture and growth. In "The Ballad of Birmingham" Randall establishes racial progress as a kind of blossoming, as he recounts the incident, based on a historical event of the bombing in 1963 of Martin Luther King, Jr.'s church by white terrorists. Eight quatrains portray one girl's life and death. (Four girls actually died in the real bombing.) When the daughter in the poem asks permission to attend a civil rights rally, the loving and fearful mother refuses to let her go. Allowed to go to church instead, the daughter dies anyway. Thus, there is no sanctuary in an evil world, Randall seems to say, and one may face horror in the street as well as in the church. After folk singer Jerry Moore read the poem in a newspaper, he set it to music, and Randall granted him permission to publish the tune with the lyrics.

From Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 41: Afro-American Poets Since 1955. A Bruccoli Clark Layman Book. Edited by Trudier Harris, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Thadious M. Davis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Copyright © 1985 by The Gale Group.

James Sullivan

[Dudley Randall’s Detroit-based Broadside Press issued a series of African-American poetry broadsides.]

The first

two in the series are poems by Randall himself: "Ballad of Birmingham" and

"Dressed All in Pink." Folk singer Jerry Lewis had set them to music, and to

ensure his own copyright of the texts, Randall published them as broadsides in 1965. In

1966, when he met Robert Hayden, Melvin Tolson, and Margaret Walker at Fisk University's

first annual Writers Conference, he asked each of them for permission to print one of

their already-published poems as a broadside--Hayden's "'Gabriel," Tolson's

"The Sea-Turtle and the Shark," and Walker's "The Ballad of the Free"

(Randall, Broadside 23). Randall also wrote Gwendolyn Brooks, asking permission to

use one of her poems. She wrote back that he could pick any one he liked, and he chose

"We Real Cool" (ibid. 8). And so he had his initial "Poems of the Negro

Revolt" sequence. Most of the first twenty-four issues of the Broadside Series

continued to be "favorite poems" that had already been published elsewhere, but

in 1968, a reviewer at Small Press Review suggested that issuing previously

unpublished poems might be a greater literary service, so beginning with Number 25,

"Assassination" by Don L. Lee--a response to the murder of Martin Luther King

Jr.--he made the series mostly a forum for new work (ibid. 2-3 ).

The first

two in the series are poems by Randall himself: "Ballad of Birmingham" and

"Dressed All in Pink." Folk singer Jerry Lewis had set them to music, and to

ensure his own copyright of the texts, Randall published them as broadsides in 1965. In

1966, when he met Robert Hayden, Melvin Tolson, and Margaret Walker at Fisk University's

first annual Writers Conference, he asked each of them for permission to print one of

their already-published poems as a broadside--Hayden's "'Gabriel," Tolson's

"The Sea-Turtle and the Shark," and Walker's "The Ballad of the Free"

(Randall, Broadside 23). Randall also wrote Gwendolyn Brooks, asking permission to

use one of her poems. She wrote back that he could pick any one he liked, and he chose

"We Real Cool" (ibid. 8). And so he had his initial "Poems of the Negro

Revolt" sequence. Most of the first twenty-four issues of the Broadside Series

continued to be "favorite poems" that had already been published elsewhere, but

in 1968, a reviewer at Small Press Review suggested that issuing previously

unpublished poems might be a greater literary service, so beginning with Number 25,

"Assassination" by Don L. Lee--a response to the murder of Martin Luther King

Jr.--he made the series mostly a forum for new work (ibid. 2-3 ).

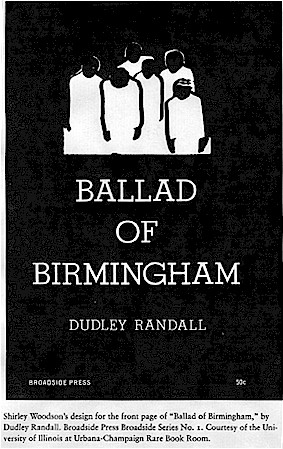

"Ballad of Birmingham" deserves special attention as the first broadside Randall published and also because it places the series in relation to the tradition of popular broadsides up through the nineteenth century that recount sensational events in ballad form. Printed up, like them, inexpensively for sale, it uses the conventions of the traditional broadside ballad for contemporary political goals. Two broadside versions of this poem exist. For the first publication in 1965, the graphics are simple: brown ink in a tasteful typeface on tan paper, priced at thirty-five cents. But once the series was established, Randall reissued the poem in a new format and with a new price, fifty cents. Though the words do not change, the second, more visually complex version connects the whole series more directly to the older tradition of poetry broadsides, and it raises issues of audience use and the role of graphic format in producing meaning that other broadsides later in the series address more fundamentally.

The folded card carries the poem inside, arranged in a fairly standard format, title across the breadth of the sheet, subtitle underneath it in parentheses--"(On the Bombing of a Church in Birmingham, Alabama, 1963)"--then the poem proper in two columns occupying most of the page: all printed in black on white. But the outside (designed by Shirley Woodson, with title and illustration on front, publication information on back) is printed all black, the text and drawing appearing as negative space in this imposed black field. The white field on the inside is a given, a publishing convention. But with the outside acting as a dark border and the text itself appearing in a typeface with heavy vertical lines, it recalls the elegiac broadsides from two or three centuries earlier. The card format and the somber illustration of six figures huddled together, heads bowed, suggest a funeral.

These generic allusions in the visual format and the title indicate that, like seventeenth- and eighteenth-century elegiac broadsides, this one will use the tragic occasion to expound upon the spiritual values of the community. The tradition of basing broadside ballads on sensational disasters and crimes further determines the poem as a tragedy. In this context, the first lines already suggest the end of the story.

"Mother dear, may I go downtown

Instead of out to play,

And March the streets of Birmingham

In a Freedom March Today?"

Given the title and subtitle, as well as the funerary implications of the card's design, this character will have to end up at that church eventually, probably to die, as ballad characters so often do. This poem uses the ballad convention of the innocent questioner and the wiser respondent (the pattern of, for example, "Lord Randall" and "La Belle Dame sans Merci"), but it changes the object of knowledge from fate to racial politics. The child is the conventional innocent, while the mother understands the violence of this political moment:

"No, baby, no, you may not go,

For the dogs are fierce and wild,

And clubs and hoses, guns and jails

Aren't good for a little child."

The mother, however, still believes that there is a place safe from racial hatred. She suggests that her daughter "may go to church instead, / And sing in the children's choir." But by the end, the horror of the bombing leaves her disillusioned:

The mother smiled to know her child

Was in a sacred place,

But that smile was the last smile

To come upon her face.For when she heard the explosion,

Her eyes grew wet and wild.

She raced through the streets of Birmingham

Calling for her child.

At the end, the child's body and the mother's naive faith in the limits of hatred and violence have been destroyed as the ballad leaves the mother transfixed among the "bits of glass and brick," where she can find only her little girl's shoe but not the girl herself.

Randall's broadside reminds the audience of what is at stake in the struggle for civil rights--no sanctuary, no respect for innocence, the potential for violent resistance not just to social change, but even to the presence, new or continued, of blacks in community with whites. There is no such thing as staying out of the struggle in order to avoid trouble. The violence touches even this woman who would keep her family out of the danger of active political protests like the Freedom March. To read, buy, have, or give the card is to participate in the struggle she could not stay out of.

Eighteenth-century broadside elegies used death as a public occasion for defining the values of the community. The dead provided a moral lesson--either an example of a good Christian death or a warning to sinners. Such broadsides disseminated Christian teachings and situated them as the values of the community. The practice of distributing such broadsides and, today, of sending sympathy cards (or, in Catholic tradition, Mass cards) reinforces, as a material expression of shared grief, commuaal bonds among the living. The group of mourners figured on the front of "Ballad of Birmingham provides a graphic model of communal grief over that bombing and other acts of racist terrorism. The card, then, was a site for recognizing a shared emotional and political response, part of a shared national identity. It contributes to that African American identity an awareness of the ubiquitous threat of racial violence. it suggests a division between those willing to risk violent injury by challenging Jim Crow through direct action and those unwilling to take such risks, but it shows, through the story of this church bombing, that the basis of that division, the risk of harm, can be the same for each group. The whole community has the same stake in social change.

From On the Walls and in the Streets: American Poetry Broadsides from the 1960s. Copyright © 1997 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois.

Return to Dudley Randall