About the 1963 Birmingham Bombing

Birmingham, Alabama, and the Civil Rights

Movement in 1963

The 16th Street Baptist Church Bombing

The

Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham was used as a meeting-place for civil rights

leaders such as Martin Luther King, Ralph David Abernathy and Fred Shutterworth. Tensions

became high when the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Congress on

Racial Equality (CORE) became involved in a campaign to register African American to vote

in Birmingham.

The

Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham was used as a meeting-place for civil rights

leaders such as Martin Luther King, Ralph David Abernathy and Fred Shutterworth. Tensions

became high when the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Congress on

Racial Equality (CORE) became involved in a campaign to register African American to vote

in Birmingham.

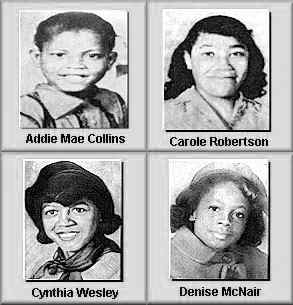

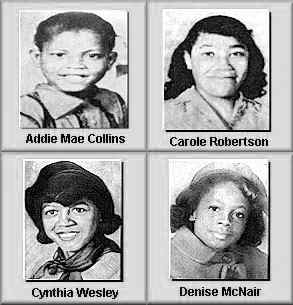

On Sunday, 15th September, 1963, a white man was seen getting out of a white and turquoise Chevrolet car and placing a box under the steps of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. Soon afterwards, at 10.22 a.m., the bomb exploded killing Denise McNair (11), Addie Mae Collins (14), Carole Robertson (14) and Cynthia Wesley (14). The four girls had been attending Sunday school classes at the church. Twenty-three other people were also hurt by the blast.

Civil rights activists blamed George Wallace, the Governor of Alabama, for the killings. Only a week before the bombing he had told the New York Times that to stop integration Alabama needed a "few first-class funerals."

A witness identified Robert Chambliss, a member of the Ku Klux Klan, as the man who placed the bomb under the steps of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. He was arrested and charged with murder and possessing a box of 122 sticks of dynamite without a permit. On 8th October, 1963, Chambliss was found not guilty of murder and received a hundred-dollar fine and a six-month jail sentence for having the dynamite.

The case was unsolved until Bill Baxley was elected attorney general of Alabama. He requested the original Federal Bureau of Investigation files on the case and discovered that the organization had accumulated a great deal of evidence against Chambliss that had not been used in the original trial.

In November, 1977 Chambliss was tried once again for the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing. Now aged 73, Chambliss was found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment. Chambliss died in an Alabama prison on 29th October, 1985.

On 17th May, 2000, the FBI announced that the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing had been carried out by the Ku Klux Klan splinter group, the Cahaba Boys. It was claimed that four men, Robert Chambliss, Herman Cash, Thomas Blanton and Bobby Cherry had been responsible for the crime. Cash was dead but Blanton and Cherry were arrested and Blanton has since been tried and convicted.

Timothy B. Tyson

|

Haven to the South's most violent Ku Klux Klan chapter, Birmingham was probably the most segregated city in the country. Dozens of unsolved bombings and police killings had terrorized the black community since World War II. Yet King foresaw that "the vulnerability of Birmingham at the cash register would provide the leverage to gain a breakthrough in the toughest city in the South."

Wyatt Tee Walker, who planned the crusade, said that before Birmingham "we had been trying to win the hearts of white Southerners, and that was a mistake, a misjudgement. We realized that you have to hit them in the pocket." Birmingham offered the perfect adversary in Public Safety Commissioner Eugene "Bull" Connor, who provided dramatic brutality for an international audience. SCLC’s [Southern Christian Leadership Conference, a civil rights organization founded in 1957] goal was to create a political morality play so compelling that the Kennedv administration would be forced to intervene: "The key to everything," King observed, "is federal commitment."

The movement initially found it hard to recruit supporters, with black citizens reluctant and Birmingham police restrained. Slapped with an injunction to cease the demonstrations, King decided to go to jail himself. During his confinement, King penned "Letter from Birmingham Jail," an eloquent critique of "the white moderate who is more devoted to 'order' than to justice" and a work included in many composition and literature courses.

The breakthrough came when SCLC’s James Bevel organized thousands of black school children to march in Birmingham. Police used school buses to arrest hundreds of children who poured into the streets each day. Lacking jail space, "Bull" Connor used dogs and firehoses to disperse the crowds. Images of vicious dogs and police brutality emblazoned front pages and television screens around the world. As in Montgomery, King grasped the international implications of SCLC’s strategy. The nation was 'battling for the minds and the hearts of men in Asia and Africa," he said, "and they aren't gonna respect the United States of America if she deprives men and women of the basic rights of life because of the color of their skin."

President Kennedy lobbied Birmingham's white business community to reach an agreement. On 10 May local white business leaders consented to desegregate public facilities, but the details of the accord mattered less than the symbolic triumph. Kennedy pledged to preserve this mediated halt to "a spectacle which was seriously damaging the reputation of both Birmingham and the country."

The next day, however, bombs exploded at King's headquarters and at his brother’s home. Violent uprisings followed, as poor

|

blacks who had little commitment to nonviolence ravaged nine blocks of Birmingham. Rocks and bottles rained on Alabama state troopers who attacked black citizens in the streets. The violence threatened to mar SCLC’s victory but also helped cement White House support for civil rights. President Kennedy feared that black Southerners might become "uncontrollable" if reforms were not negotiated. It was one of the enduring ironies of the civil fights movement that the threat of violence was so critical to the success of nonviolence.

Across the South, the triumph in Birmingham inspired similar campaigns; in a ten-week period, at least 758 racial demonstrations in 186 cities sparked 14,733 arrests. Eager to compete with SCLC, the national NAACP pressed Medgar Evers to launch demonstrations in Jackson, Mississippi, On 11 June President Kennedy made a historic address on national television, describing civil rights as "a moral issue" and endorsing federal civil rights legislation. Later that night, a member of the White Citizen’s Council assassinated Medgar Evers.

Tragedy and triumph marked the summer of 1963. As A. Philip Randolph sought to fulfill his vision of a march on the capitol for jobs, King convinced him to shift the focus to civil rights. Joining with leaders from SCLC, SNCC, the Urban League, and the NAACP, Randolph chose Bayard Rustin as march organizer. Kennedy endorsed the march, hoping to gain support for the pending civil rights bill. On 28 August about 250,000 rallied in the most memorable mass demonstration in American history. King's "I Have a Dream" oration would endure as a historical emblem of nonviolent direct action. Prominent in the crowd was writer James Baldwin, widely regarded as a black spokesperson, especially since the 1962 publication of his influential work, The Fire Next Time. Malcolm X’s denunciation of the event as the "farce on Washington" and sharp differences over the censorship of a speech by SNCC’s John Lewis would later seem to foreshadow the fragmentation of the movement. But against the lengthening shadow of political violence and racial division--the dynamite murder of four black children at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham two weeks later and the assassination of President Kennedy on November 22--the march gleamed as the apex of interracial liberalism. Toni Morrison used the bombing of the church as part of the rationale for her characters forming a black vigilante group in Song of Solomon.

From The Oxford Companion to African American Literature. Copyright © 1997 by Oxford University Press.

Patricia Sullivan

Less than a month after the March on Washington, the sense of foreboding articulated by Malcolm X overshadowed the euphoria of that extraordinary late summer day. On September 15 white terrorists dynamited the basement of Birmingham's Sixteenth Street Baptist Church during Sunday School, killing four young girls: Denise McNair and Cynthia Wesley, both 11 years old, and Carole Robertson and Addie Mae Collins, both 14. Dreading that the families would blame him for exposing the children to risk, King returned to Birmingham and presided over the funeral of the movement's youngest victims.

UPI News Report of the Birmingham Church BombingFrom Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Expereince. Copyright © 1999 by Kwame Anthony Appiah and Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

News Stories about the Bombing

Six Dead After Church Bombing

Six Dead After Church Bombing

Blast Kills Four Children; Riots Follow

Two Youths Slain; State Reinforces

Birmingham Police

United Press International

September 16, 1963

Birmingham, Sept. 15 -- A bomb hurled from a passing car blasted a crowded Negro church today, killing four girls in their Sunday school classes and triggering outbreaks of violence that left two more persons dead in the streets.

Two Negro youths were killed in outbreaks of shooting seven hours after the 16th Street Baptist Church was bombed, and a third was wounded.

As darkness closed over the city hours later, shots crackled sporadically in the Negro sections. Stones smashed into cars driven by whites.

Five Fires Reported

Police reported at least five fires in Negro business establishments tonight. A official said some are being set, including one at a mop factory touched off by gasoline thrown on the building. The fires were brought under control and there were no injuries.

Meanwhile, NAACP Executive Secretary Roy Wilkins wired President Kennedy that unless the Federal Government offers more than "picayune and piecemeal aid against this type of bestiality" Negroes will "employ such methods as our desperation may dictate in defense of the lives of our people."

Reinforced police units patrolled the city and 500 battle-dressed National Guardsmen stood by at an armory.

City police shot a 16-year-old Negro to death when he refused to heed their commands to halt after they caught him stoning cars. A 13-year-old Negro boy was shot and killed as he rode his bicycle in a suburban area north of the city.

Police Battle Crowd

Downtown streets were deserted after dark and police urged white and Negro parents to keep their children off the streets.

Thousands of hysterical Negroes poured into the area around the church this morning and police fought for two hours, firing rifles into the air to control them.

When the crowd broke up, scattered shootings and stonings erupted through the city during the afternoon and tonight.

The Negro youth killed by police was Johnny Robinson, 16. They said he fled down an alley when they caught him stoning cars. They shot him when he refused to halt.

The 13-year-old boy killed outside the city was Virgil Ware. He was shot at about the same time as Robinson.

Shortly after the bombing police broke up a rally of white students protesting the desegregation of three Birmingham schools last week. A motorcade of militant adult segregationists apparently en route to the student rally was disbanded.

Police patrols, augmented by 300 State troopers sent into the city by Gov. George C. Wallace, quickly broke up all gatherings of white and Negroes. Wallace sent the troopers and ordered 500 National Guardsmen to stand by at Birmingham armories.

King arrived in the city tonight and went into a conference with Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, a leader in the civil rights fight in Birmingham.

The City Council held an emergency meeting to discuss safety measures for the city, but rejected proposals for a curfew.

Dozens of persons were injured when the bomb went off in the church, which held 400 Negroes at the time, including 80 children. It was Young Day at the church.

A few hours later, police picked up two white men, questioned them about the bombing and released them.

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. wired President Kennedy from Atlanta that he was going to Birmingham to plead with Negroes to "remain non-violent."

But he said that unless "immediate Federal steps are taken" there will be "in Birmingham and Alabama the worst racial holocaust this Nation has ever seen."

Dozens of survivors, their faces dripping blood from the glass that flew out of the church's stained glass windows, staggered around the building in a cloud of white dust raised by the explosion. The blast crushed two nearby cars like toys and blew out windows blocks away.

Negroes stoned cars in other sections of Birmingham and police exchanged shots with a Negro firing wild shotgun blasts two blocks from the church. It took officers two hours to disperse the screaming, surging crowd of 2,000 Negroes who ran to the church at the sound of the blast.

At least 20 persons were hurt badly enough by the blast to be treated at hospitals. Many more, cut and bruised by flying debris, were treated privately.

(The Associated Press reported that among the injured in subsequent shooting were a white man injured by a Negro. Another white man was wounded by a Negro who attempted to rob him, according to police.)

Mayor Albert Boutwell, tears streaming down his cheeks, announced the city had asked for help.

"It is a tragic event," Boutwell said. "It is just sickening that a few individuals could commit such a horrible atrocity. The occurrence of such a thing has so gravely concerned the public..." His voice broke and he could not go on.

Boutwell and Police Chief Jamie Moore requested the State assistance in a telegram to Wallace.

"While the situation appears to be well under control of federal law enforcement officers at this time, the possibility of further trouble exists," Boutwell and Moore said in their telegram.

President Kennedy, yachting off Newport, R.I., was notified by radio-telephone and Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy ordered his chief civil rights troubleshooter, Burke Marshall, to Birmingham. At least 25 FBI agents, including bomb experts from Washington, were being rushed in.

City Police Inspector W.J. Haley said as many as 15 sticks of dynamite must have been used.

"We have talked to witnesses who say they saw a car drive by and then speed away just before the bomb hit," he said.

In Montgomery, Wallace said he had a similar report and said the descriptions of the car's occupants did not make clear their race. But he served notice "on those responsible that every law enforcement agency of this State will be used to apprehend them."

The bombing was the 21st in Birmingham in eight years, and the first to kill. None of the bombings have been solved.

As police struggled to hold back the crowd, the blasted church's pastor, the Rev. John H. Cross, grabbed a megaphone and walked back and forth, telling the crowd: "The police are doing everything they can. Please go home."

"The Lord is our shepherd," he sobbed. "We shall not want."

The only stained glass window in the church that remained in its frame showed Christ leading a group of little children. The face of Christ was blown out.

After the police dispersed the hysterical crowds, workmen with pickaxes went into the wrecked basement of the church. Parts of brightly painted children's furniture were strewn about in one Sunday School room, and blood stained the floors. Chunks of concrete the size of footballs littered the basement.

The bomb apparently went off in an unoccupied basement room and blew down the wall, sending stone and debris flying like shrapnel into a room where children were assembling for closing prayers following Sunday School. Bibles and song books lay shredded and scattered through the church.

In the main sanctuary upstairs, which holds about 500 persons, the pulpit and Bible were covered with pieces of stained glass.

One of the dead girls was decapitated. The coroner's office identified the dead as Denise McNair, 11; Carol Robertson, 14; Cynthia Wesley, 14, and Addie Mae Collins, 10.

As the crowd came outside watched the victims being carried out, one youth broke away and tried to touch one of the blanket-covered forms.

"This is my sister," he cried. "My God, she's dead." Police took the hysterical boy away.

Mamie Grier, superintendent of the Sunday School, said when the bomb went off "people began screaming, almost stampeding" to get outside. The wounded walked around in a daze, she said.

One of the injured taken to a hospital was a white man. Many others cut by flying glass and other debris were not treated at hospitals.

Fourth in Four Weeks

It was the fourth bombing in four weeks in Birmingham, and the third since the current school desegregation crisis came to a boil Sept. 4.

Desegregation of schools in Birmingham, Mobile, and Tuskegee was finally brought about last Wednesday when President Kennedy federalized the National Guard. Some of the Guardsmen in Birmingham are still under Federal orders. Wallace said the ones he alerted today were units of the Guard "not now federalized."

The City of Birmingham has offered a $52,000 reward for the arrest of the bombers, and Wallace today offered another $5,000.

Dr. King Berates Wallace

But Dr. King wired Wallace that "the blood of four little children ... is on your hands. Your irresponsible and misguided actions have created in Birmingham and Alabama the atmosphere that has induced continued violence and now murder."

Online Source: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/longterm/churches/archives1.htm

Killer of the Innocents -- Commentary

Birmingham World -- Sept. 18, 1963

Lethal dynamite has made Sunday, September 15, 1963, a Day of Sorrow and Shame in Birmingham, Alabama, the world's chief city of unsolved racial bombings.

Four or more who were attending Sunday School at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church on the day of Sorrow and Shame were killed. Their bodies were stacked up on top of each other like bales of hay from the crumbling ruins left by the dynamiting. They were girls. They were children. They were members of the the Negro group. They were victims of cruel madness, the vile bigotry and the deadly hate of unknown persons.

Society in a free country has a solemn responsibility to itself and those who make it up. Free men are bound by an irrevocable civic contract to safeguard the rights, safety, and security of all of its members. This is the basic issue in what is happening in Birmingham. The continued unsolved racial bombings tend to suggest the deterioration of society in this city.

Our neighborhood and church leaders has also the challenge of seeking some lofty, but real self-defense strategy and technique. Patience is a human element and subject to no less frailties. The unsolved bombings have taxed patience and aroused unquenchable fears - fears of police, of the sincerity of public leaders, and of the quality of Negro leadership in this City of Sorrow and Shame.

To the families of the bombed victims, the Birmingham World offers its sympathy. To the pastor and the members of Sixteenth Street Baptist Church we offer a friendly hand. We are angered by the murderous bombing ad shocked by the lack of solution. The Birmingham World has been in the struggle against this kind of insanity, intolerance, disrespect of the House of God, defiance of established law, and disregard of human values since its beginning which the bombings substantiate. We shall try to carry on in the struggle, believing in the divine goodness. We have that overcoming faith in a Higher Being to guide us.

Those who died in the September 15,bombing also died serving the Lord Jesus Christ, who was crucified. This will be an unforgettable day in our nation, in world history,; in the new rebellion of which the Confederate flags seem to symbolize. Yet, if members of the Negro group pour into the churches on Sunday, stream to the voter-registration offices, make their dollars talk freedom, and build up a better leadership, those children might not have died in vain.

The Negro group in Birmingham is unhappy. The Negro group is dissatisfied with the kind of protection they are getting. The Negro group is disturbed when law enforcement remains all-white in Birmingham and in Jefferson County. The Negro group is disappointed with the lack of more help from the Federal Government. This makes Birmingham a city of uneasiness for the Negro group.

Where does Birmingham go from here? The huge bomb reward fund grows bigger, but the bombings solution does not seem to be near. Governor George Wallace says he stands for law and order but he seems to attract the support of the negative forces whose credo inspires less. From the lips of the Governor come assertions which seem to imply defiance of the Supreme Court decision on schools.

Is Birmingham a sick city? We cannot answer for sure. There are tensions because there is fear...there is a feeling of diminishing faith in City Hall to measure up to the responsibility of the kind of municipal leadership needed in his City of Sorrow and Shame. The killers of the innocents have challenged the conscience of decent person everywhere.

Neither the living who were bombed nor those who have not been bombed should give ground to the bombers. The United States government and other law enforcement agents must leave no stone unturned until the perpetrators of this heinous crime are brought to justice

"Birmingham Bombing"

On Sunday, September 15, 1963, a bomb went off at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. Four girls in the ladies lounge were instantly killed. Though no other act of terror during the course of the civil rights movement would claim as many lives, the case was never cracked.

In July 1997 the Justice Department and the state of Alabama announced that they had reopened the investigation. This threw fresh light on the murky subculture of truck-stop racists that was at the heart of the South worst moments and on how J. Edgar Hoover's peculiarities may have helped the guilty men go unpunished. By coincidence, Spike Lee has just released a documentary on the church bombing, "4 Little Girls."

The probe is a part of a larger, more important trend: a series of visits back into the deadly days of the movement. First came the 1994 conviction of Byron de la Beckwith for the 1963 assassination of Medgar Evers; James Earl ray, Martin Luther King jr.' convicted killer, wants a new trial. The interest in these long-dormant cases is a sign that the New South is still desperate to make sense of the bloody baggage of the Old.

In the Birmingham of the early 1960s, 16th Street Baptist Church was a natural target. King used it as staging ground for his marches against segregation and the integration of the city's schools had just gotten underway. Even before the Sunday-morning blast, Birmingham had become known as "Bomingham" on account of the city's violent KKK chapter, Eastveiw Klavern 13.

It took Alabama 14 years to convict one of the terrorists "Dynamite Bob" Chambliss. Other coconspirators, whose identities were known to the authorities, were left alone. The central problem was the FBI. The then director J. Edgar Hoover disliked King, but the director had other reasons, too. He focused the FBI's resources on sure things, and he doubted that a white Alabama jury would convict the men. And he was reluctant to reveal his informants and questionable wiretapping in court.

According to FBI files, there were at least five potential members of the bombing conspiracy. Whatever the specifics turn out to be, the case is proof positive that William Faulkner had it right: in the south, he once wrote, "the past is never dead. It isn't even past."

Jury Convicts Ex-Klansman

Associated Press, Monday, July 9, 2001

A former Ku Klux Klansman was convicted of murder Tuesday for the 1963 church bombing that killed four black girls, the deadliest single attack during the civil rights movement.

Thomas Blanton Jr., 62, was sentenced to life in prison by the same jury that found him guilty after 2½ hours of deliberations. Before he was led out of the courtroom in handcuffs, the judge asked him if he had any comment.

"I guess the good Lord will settle it on judgment day," Blanton said.

Blanton is the second former Klansman to be convicted of planting the bomb that went off at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church on Sept. 15, 1963, a Sunday morning.

The bomb ripped through an exterior wall of the brick church. The bodies of Denise McNair, 11, and Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley and Carole Robertson, all 14, were found in the downstairs lounge.

Denise's parents, Chris and Maxine McNair, did not comment as they left the courthouse. Chris McNair was hugged by U.S. Attorney Doug Jones, who fought back tears as he told reporters: "We're happy for the families. We're happy for the girls."

The Rev. Abraham Woods, a black minister instrumental in getting the FBI to reopen the case in 1993, said he was delighted with the verdict.

"It makes a statement on how far we've come," said Woods, the local president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

"We're mindful that this verdict will not bring back the lives of the four little girls," added Kweisi Mfume, head of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, in a statement. "(But) justice has finally been served."

Defense attorney John Robbins said the swift verdict showed the jury was caught up in the emotion surrounding the notorious case. He said he would seek a new trial, arguing the case should have been moved out of Birmingham and Blanton's right to a speedy trial had been violated.

He also said the lack of white men on the jury -- eight white women, three black women and one black man returned the verdict -- "absolutely hurt Blanton." The jurors, who were publicly identified only by number, left without comment.

The case is the latest from the turbulent civil rights era to be revived by prosecutors. Byron De La Beckwith was convicted in 1994 of assassinating civil rights leader Medgar Evers in 1963 and former Klan imperial wizard Sam Bowers was convicted three years ago of the 1966 firebomb-killing of an NAACP leader.

But the church bombing was a galvanizing moment of the civil rights movement. Moderates could no longer remain silent and the fight to topple segregation laws gained new momentum.

During closing arguments, Jones told the jury that it was "never too late for justice."

He said Blanton acted in response to months of civil rights demonstrations. The church had become a rallying point for protesters.

"Tom Blanton saw change and didn't like it," Jones said as black-and-white images of the church and the girls dressed in Sunday clothing flashed on video screens in the courtroom.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Robert Posey added: "The defendant didn't care who he killed as long as he killed someone and as long as that person was black."

"These children must not have died in vain," he said. "Don't let the deafening blast of his bomb be what's left ringing in our ears."

Robbins argued that the government had proved only that Blanton was once a foul-mouthed segregationist, not a bomber. He said murky tapes of his client secretly recorded by the FBI were illegally obtained and should not have been admitted as evidence.

The surveillance began after Blanton and other Klansman were identified as suspects within weeks of the bombing.

The FBI planted a hidden microphone in Blanton's apartment in 1964 and taped his conversations with Mitchell Burns, a fellow Klansman-turned-informant.

Posey went over the tapes for jurors, putting transcript excerpts on the video screens. He read from one transcript in which Blanton described himself to Burns as a clean-cut guy: "I like to go shooting, I like to go fishing, I like to go bombing."

Posey also quoted Blanton as saying he was through with women. "I am going to stick to bombing churches," Blanton said, according to Posey.

On one tape, Blanton was heard telling Burns that he would not be caught "when I bomb my next church." On another made in his kitchen, he is heard talking with his wife about a meeting where "we planned the bomb."

"That is a confession out of this man's mouth," said Jones, pointing to Blanton.

The defense argued that the tape made in Blanton's kitchen meant nothing because prosecutors failed to play 26 minutes of previous conversation. "You can't judge a conversation in a vacuum," Robbins said.

Robbins also said Blanton's conversations with Burns were nothing but boasting between "two drunk rednecks." He dismissed Burns and other prosecution witnesses as liars.

Another former Klan member, Robert "Dynamite Bob" Chambliss, was convicted of murder in 1977 and died in prison in 1985.

Another former Klansman, Bobby Frank Cherry, was indicted last year but his trial was delayed after evaluations raised questions about his mental competency. A fourth suspect, Herman Cash, died without being charged.

The Justice Department concluded 20 years ago that former FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover had blocked prosecution of Klansmen in the bombing. The case was reopened following a 1993 meeting in Birmingham between FBI officials and black ministers, including Woods.

The investigation was not revealed publicly until 1997, when agents went to Texas to talk to Cherry.

About the Girls

"The Day The

Children Died"

People Magazine

by Kyle Smith, Gail Cameron Wescott in Birmingham and David Cobb Craig in New

York City

Photographs by Ann States/SABA

SUNDAY SCHOOL HAD JUST LET OUT, and Sarah Collins Cox, then 12, was in the basement with her sister Addie Mae, 14, and Denise McNair, 11, a friend, getting ready to attend a youth service. "I remember Denise asking Addie to tie her belt," Cox, now 46, says in a near whisper, recalling the morning of Sept. 15, 1963. "Addie was tying her sash. Then it happened." A savage explosion of 19 sticks of dynamite stashed under a stairwell ripped through the northeast corner of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. "I couldn't see anymore because my eyes were full of glass - 23 pieces of glass," says Cox. "I didn't know what happened. I just remember calling, 'Addie, Addie.' But there was no answer. I don't remember any pain. I just remember wanting Addie."

That afternoon, while Cox's parents comforted her at the hospital, her older sister Junie, 16, who had survived the bombing unscathed, was taken to the University Hospital morgue to help identify a body. "I looked at the face, and I couldn't tell who it was," she says of the crumpled form she viewed. "Then I saw this little brown shoe - you know, like a loafer - and I recognized it right away."

Addie Mae Collins was one of four girls killed in the blast. Denise McNair; Carole Robertson, 14; and Cynthia Wesley, 14, also died, and another 22 adults and children were injured. Meant to slow the growing civil rights movement in the South, the racist killings, like the notorious murder of activist Medgar Evers in Mississippi three months earlier, instead fueled protests that helped speed passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

"The bombing was a pivotal turning point," says Chris Hamlin, the current pastor of the Sixteenth Street church, whose modest basement memorial to the girls receives 80,000 visitors annually. Birmingham - so rocked by violence in the years leading up to the blast that it became known as Bombingham - "Finally," adds Hamlin, "began to say to itself, 'This is enough!'"

The Justice Department is saying it too. Last month it announced it had reopened the probe into the bombing, delivering the statement a day after the theatrical release of 4 Little Girls, a Spike Lee documentary about the attack that will play in 10 cities before airing on HBO in February.

Robert "Dynamite Bob" Chambliss, a truck driver and longtime Ku Klux Klan member, was convicted of the murders in 1977. Though the FBI always believed had had accomplices, even identifying three suspects, the case against them was marred by conflicting accounts, and Chambliss, who died in prison at age 81 in 1985, refused to the end to cooperate. But new leads that emerged a year ago have made the FBI cautiously hopeful. "You have an old case, and we don't want to raise expectations too high," says Craig Dahle, an FBI spokesman in Birmingham, "but we would not have reopened the case if we did not believe there was a possibility of solving it."

Still, the community holds some hope for final justice (the case was reopened in 1980 and 1988 without arrests) for the young martyrs. Denise McNair, the daughter of photo shop owner Chris and schoolteacher Maxine, was an inquisitive girl who never understood why she couldn't get a sandwich at the same counter as white children. Carole Robertson, whose father was a band master at an elementary school and whose mother was a librarian, was an avid reader, dancer and clarinet player. Cynthia Wesley, whose parents were also teachers, left the house that day having been admonished by her mother to adjust her slip to be presentable in church.

Addie's family was the poorest of the four. She was one of seven children born to Oscar Collins, a janitor, and Alice, a homemaker. "It was clear that she lacked things," recalls Rev. John Cross, the pastor of the church at the time of the bombing. "But she was a quiet, sweet girl." And, Sarah adds, a budding artist: "She could draw people real good."

It is no surprise that Sarah and her sister Junie have never fully shaken off the horror of that day 34 years ago. "I never smiled, and I never talked about what had happened," says Junie. "Then, back in 1985, someone told me that it was going to destroy me if I didn't start talking about it. So I did. I ended up checking into Brookwood (Medical Center, for psychotherapy) for 37 days."

Junie, like Sarah, now works as a housekeeper. Her employer, plastic surgeon Dr. Peter Bunting, had no notion of her connection to the bombing when he hired her. "I almost fell off my stool when she told me," he says, adding that while Junie holds no grudge, "I think she will always be in a state of healing - which is true of the city too." Junie lives in a spacious one-story home and is a member of a small church congregation called Fellowship West.

"She is queen," says Christopher Williams, "always so positive and outgoing that it's hard for me to imagine the timid, nervous person she says she was for so many years. She told me that she thinks she's finally crossed the bridge from the bombing, and I said, "Maybe you are the bridge."

After the blast, Sarah's face was so drenched in blood, says Cross, that "when they asked me who she was, I had to say I had no idea." In the hospital, Sarah, whose eyes were bandaged, wondered why Addie didn't visit with the rest of the family. Her sister Janie told her that "Addie's back is hurting." Sarah learned of Addie's death when she overheard Janie talking to a nurse. "It hurt real bad," Sarah says. "I just didn't know what I would do without Addie." Sarah spent three months in the hospital, ultimately losing her right eye (she now suffers from glaucoma in her left).

She worked as a short-order cook after high school and was married for three years to a city worker before she took a foundry job, which she held for 16 years. In 1988, she married Leroy Cox, a mechanic, and the two live together in a small, cheerful prefab house; a statue of the Virgin Mary graces its tiny front yard. Sarah's family members say she has always been the peacemaker, even as she struggled to find peace for herself. "In 1989," Sarah recalls, "a prophet called out to me at church and prayed for me to be relieved of my nervousness and fear. It has been better since then. The panic attacks in the middle of the night finally subsided."

What most concerns Sarah and Junie now is the forlorn state of Addie's grave site in a cemetery so close to the Birmingham airport that the roar of jets seem to mock the mourners below. The grass is overgrown, and a dirt road leading there is rutted, but Junie and Sarah can't afford to move their sister. "It is," says Junie, standing over the grave at dusk on a hot Alabama evening, "like an open sore to us."

Profiles of the victims

Addie Mae Collins

Addie Mae Collins and two of her sisters would go door to door every day after school, selling their mother's handmade cotton aprons and potholders.

The trio collected 35 cents for potholders and 50 cents for aprons. The bibbed aprons netted 75 cents.

"Addie liked to do it. She looked forward to it," said sister Sarah, now Sarah Rudolph. "We sold a lot of them."

When she wasn't selling her mother's wares, Addie liked to play hopscotch, sing in the church choir, draw portraits, and wear bright colors.

The Hill Elementary School eighth-grader loved to pitch while playing ball, too. "I remember that underhand," said older sister Janie, now Janie Gaines.

She also remembers Addie's spirit. "She wasn't a shy or timid person. Addie was a courageous person."

Addie, born April 18, 1949, was the seventh of eight children born to Oscar and Alice Collins. When disagreements erupted among the siblings inside the home on Sixth Court West, Addie was the peacemaker.

"She just always wanted us to love one another and treat each other right," Mrs. Rudolph said. "She was a happy person also, and she loved life."

The routine was the same every Saturday night at the Collins household - starching Sunday dresses for church. Sept. 14, 1963, was no different when Addie pulled out a white dress. Older sister Flora pressed and curled Addie's short hair.

"We thought it looked pretty on her," said Mrs. Gaines.

When Addie died in the explosion, Mrs. Rudolph lost her right eye. "I feel like I lost my best friend," said Mrs. Rudolph. "We were always going places together."

Four broken columns in Birmingham's downtown Kelly Ingram Park and the nook in the basement of Sixteenth Street Baptist Church are both memorials to the four girls killed in the 1963 church bombing.

For 29-year-old Sonya Jones, that is not enough. In January, she renamed her 1-year-old youth center in memory of an aunt she never knew.

Every second and third Saturday, children file into the Addie Mae Collins Youth Center in an Ishkooda Road church to build positive attitudes, develop talents and learn to deal with adversity.

"Not only will it be a memorial to her but also we'll be helping other kids who are dealing with tragedies," said Mrs. Jones, whose mother is Janie Gaines.

Cynthia Wesley

There were times when Cynthia Wesley's father came home weary after a night of patrolling his Smithfield neighborhood for would-be mischief-makers. Or worse, bombers.

Claude A. Wesley was one of several men who volunteered to ensure another peaceful night on Dynamite Hill, nicknamed for the frequent and unsolved bombings in a former white neighborhood that was increasingly a home to blacks.

The Wesleys tried to protect their daughter from segregation's brutality.

"We were extremely naive," remembers friend and playmate Karen Floyd Savage. "We didn't really discuss things in depth like that."

The first adopted daughter of Claude and Gertrude Wesley, Cynthia was a petite girl with a narrow face and size 2 dress. Cynthia's mother made her clothes, which fit her thin frame perfectly.

She attended the now-defunct Ullman High School, where she did well in math, reading and the band. She invited friends to parties in her back yard, playing soulful tunes and serving refreshments. She was born April 30, 1949.

"Cynthia was just full of fun all the time," Mrs. Savage said. "We were constantly laughing."

It was while the two girls attended Wilkerson Elementary School that Cynthia traded her gold-band ring topped with a clear, rectangular stone for a 1954 class ring that belonged to Mrs. Savage.

"We just sort of liked each others' rings and we just traded with no question of wanting it back," Mrs. Savage said.

Cynthia made friends easily, talking often to close pal Rickey Powell. On Sept. 14, 1963, she invited Rickey to church the next day for a Sunday youth program. Powell accepted, only to reluctantly decline when his mother wanted him to accompany her to a funeral.

"We were like peas in a pod," Powell said. "That was my best bud."

When Cynthia died in the church blast, she was still wearing the ring Mrs. Savage gave her when they were younger. Cynthia's father identified her by that ring when he went to the morgue.

The death of the four girls crushed Mrs. Savage.

"I was so young. I never realized someone would hate you so much that they would go to that extent. In a way, that was sort of the death of my own innocence."

Denise McNair

Denise McNair liked her dolls, left mudpies in the mailbox for childhood crushes and organized a neighborhood fund-raiser to fight muscular dystrophy.

Born Nov. 17, 1951, Carol Denise McNair was the first child of Chris and Maxine McNair. Her playmates called her Niecie.

A pupil at Center Street Elementary School, she had a knack of gathering neighborhood children to play on the block. She held tea parties, belonged to the Brownies and played baseball.

"Everybody liked her even if they didn't like each other,"said childhood friend Rhonda Nunn Thomas. "She could play with anybody."

She and Rhonda would dream of husbands, children and careers. "At one point I would be delivering babies and she was going to be the pediatrician,"Mrs. Thomas said.

At some point in her young life, Denise asked the neighborhood children to put on skits and dance routines and to read poetry in a big production to raise money for muscular dystrophy. It became an annual event. People gathered in the yard to watch the show in Denise's carport — the main stage. Children donated their pennies, dimes and nickels. Adults gave larger sums.

The muscular dystrophy fund-raiser was always Denise's project — one that nobody refused.

"It was the idea we were doing something special for some kids,"Mrs. Thomas said. "How could you turn it down?"

A relative always thought the girl with the thick, shoulder-length hair and sparkling eyes would be a teacher because she was "a leader from the heart."

Friend and retired dentist Florita Jamison Askew remembers Denise as a child who smiled a lot, even for the camera when she lost her baby teeth.

"She was always a ham,"Mrs. Askew said.

"I bet she would have been a real go-getter. She and Carole (Robertson) both. I just wonder sometimes."

Carole Robertson

Smithfield Recreation Center's auditorium became a dance school every Saturday afternoon when eager girls arrived for lessons in tap, ballet and modern jazz.

Carole Robertson, wearing a leotard and toting black patent leather tap shoes and pink ballet slippers, was among the crowd.

"We didn't have any problems getting our chores done so we could get to dancing class on Saturdays,"said Florita Jamison Askew, who attended classes with Carole and Carole's big sister."Nobody ever wanted to miss them."

Students worked hard on their ballet and shuffle steps in preparation for the annual spring recital, where they got to wear makeup and dance with their hair down."It was a lot of fun,"Mrs. Askew said.

Born April 24, 1949, Carole was the third child of Alpha and Alvin Robertson. Older siblings were Dianne and Alvin.

Carole was an avid reader and straight-A student who belonged to Jack and Jill of America, the Girl Scouts, the Parker High School marching band and science club. She also had attended Wilkerson Elementary School, where she sang in the choir.

Carole walked fast and with a smile.

"She moved through the halls rapidly, not running, but just full of life,"said retired Birmingham teacher Lottie Palmer, who was a science club sponsor."She was a girl that was anxious to .¤.¤. succeed and do well.

Carole grew up in a Smithfield home that was full of love, friends and the aroma of good cooking, especially her mother's spaghetti.

"There was a lot of warmth in the house. The food was good and the people were kind," Mrs. Askew said."That was kind of my second home."

Inside the one-story home with the wrap-around porch, Mrs. Askew and the Robertson girls practiced dances such as the cha-cha and tried out different hairstyles — often on Carole, who didn't mind being the model.

Carole once told Mrs. Askew, now a retired dentist, about her desire to preserve the past.

"I remember a statement she made — she wanted to teach history or do something his torical. I thought how ironic it was that she would remain a part of history forever."

In 1976, Chicago residents established the Carole Robertson Center for Learning, a social service agency that serves children and their families. Named after Carole, it is dedicated to the memory of all four girls.

Members of the Jack and Jill choir were scheduled to sing at Carole's funeral Sept. 17, 1963, at St. John AME Church."Of course, we didn't do much singing,"said choir member Karen Floyd Savage."We cried through it."

by Chanda Temple © The Birmingham News. Online Source

18 September 1963

Birmingham, Ala.

[Delivered at funeral service for three of the children—Addie Mae Collins, Carol Denise McNair, and Cynthia Diane Wesley—killed in the bombing. A separate service was held for the fourth victim, Carole Robertson.]

This afternoon we gather in the quiet of this sanctuary to pay our last tribute of respect to these beautiful children of God. They entered the stage of history just a few years ago, and in the brief years that they were privileged to act on this mortal stage, they played their parts exceedingly well. Now the curtain falls; they move through the exit; the drama of their earthly life comes to a close. They are now committed back to that eternity from which they came.

These children—unoffending, innocent, and beautiful—were the victims of one of the most vicious and tragic crimes ever perpetrated against humanity.

And yet they died nobly. They are the martyred heroines of a holy crusade for freedom and human dignity. And so this afternoon in a real sense they have something to say to each of us in their death. They have something to say to every minister of the gospel who has remained silent behind the safe security of stained-glass windows. They have something to say to every politician [Audience:] (Yeah) who has fed his constituents with the stale bread of hatred and the spoiled meat of racism. They have something to say to a federal government that has compromised with the undemocratic practices of southern Dixiecrats (Yeah) and the blatant hypocrisy of right-wing northern Republicans. (Speak) They have something to say to every Negro (Yeah) who has passively accepted the evil system of segregation and who has stood on the sidelines in a mighty struggle for justice. They say to each of us, black and white alike, that we must substitute courage for caution. They say to us that we must be concerned not merely about who murdered them, but about the system, the way of life, the philosophy which produced the murderers. Their death says to us that we must work passionately and unrelentingly for the realization of the American dream.

And so my friends, they did not die in vain. (Yeah) God still has a way of wringing good out of evil. (Oh yes) And history has proven over and over again that unmerited suffering is redemptive. The innocent blood of these little girls may well serve as a redemptive force (Yeah) that will bring new light to this dark city. (Yeah) The holy Scripture says, "A little child shall lead them." (Oh yeah) The death of these little children may lead our whole Southland (Yeah) from the low road of man's inhumanity to man to the high road of peace and brotherhood. (Yeah, Yes) These tragic deaths may lead our nation to substitute an aristocracy of character for an aristocracy of color. The spilled blood of these innocent girls may cause the whole citizenry of Birmingham (Yeah) to transform the negative extremes of a dark past into the positive extremes of a bright future. Indeed this tragic event may cause the white South to come to terms with its conscience. (Yeah)

And so I stand here to say this afternoon to all assembled here, that in spite of the darkness of this hour (Yeah Well), we must not despair. (Yeah, Well) We must not become bitter (Yeah, That’s right), nor must we harbor the desire to retaliate with violence. No, we must not lose faith in our white brothers. (Yeah, Yes) Somehow we must believe that the most misguided among them can learn to respect the dignity and the worth of all human personality.

May I now say a word to you, the members of the bereaved families? It is almost impossible to say anything that can console you at this difficult hour and remove the deep clouds of disappointment which are floating in your mental skies. But I hope you can find a little consolation from the universality of this experience. Death comes to every individual. There is an amazing democracy about death. It is not aristocracy for some of the people, but a democracy for all of the people. Kings die and beggars die; rich men and poor men die; old people die and young people die. Death comes to the innocent and it comes to the guilty. Death is the irreducible common denominator of all men.

I hope you can find some consolation from Christianity's affirmation that death is not the end. Death is not a period that ends the great sentence of life, but a comma that punctuates it to more lofty significance. Death is not a blind alley that leads the human race into a state of nothingness, but an open door which leads man into life eternal. Let this daring faith, this great invincible surmise, be your sustaining power during these trying days.

Now I say to you in conclusion, life is hard, at times as hard as crucible steel. It has its bleak and difficult moments. Like the ever-flowing waters of the river, life has its moments of drought and its moments of flood. (Yeah, Yes) Like the ever-changing cycle of the seasons, life has the soothing warmth of its summers and the piercing chill of its winters. (Yeah) And if one will hold on, he will discover that God walks with him (Yeah, Well), and that God is able (Yeah, Yes) to lift you from the fatigue of despair to the buoyancy of hope, and transform dark and desolate valleys into sunlit paths of inner peace.

And so today, you do not walk alone. You gave to this world wonderful children. [moans] They didn’t live long lives, but they lived meaningful lives. (Well) Their lives were distressingly small in quantity, but glowingly large in quality. (Yeah) And no greater tribute can be paid to you as parents, and no greater epitaph can come to them as children, than where they died and what they were doing when they died. (Yeah) They did not die in the dives and dens of Birmingham (Yeah, Well), nor did they die discussing and listening to filthy jokes. (Yeah) They died between the sacred walls of the church of God (Yeah, Yes), and they were discussing the eternal meaning (Yes) of love. This stands out as a beautiful, beautiful thing for all generations. (Yes) Shakespeare had Horatio to say some beautiful words as he stood over the dead body of Hamlet. And today, as I stand over the remains of these beautiful, darling girls, I paraphrase the words of Shakespeare: (Yeah, Well): Good night, sweet princesses. Good night, those who symbolize a new day. (Yeah, Yes) And may the flight of angels (That’s right) take thee to thy eternal rest. God bless you.

Richard Farina's 1964 Song "Birmingham Sunday"

Lyrics as reprinted in Guy and Candie Carawan, Sing for Freedom: The Story of the Civil Rights Movement through its songs, Bethlehem, PA, 1990, pp. 122-123.

Come round by my side and I'll sing you a song.

I'll sing it so softly, it'll do no one wrong.

On Birmingham Sunday the blood ran like wine,

And the choirs kept singing of Freedom.

That cold autumn morning no eyes saw the sun,

And Addie Mae Collins, her number was one.

At an old Baptist church there was no need to run.

And the choirs kept singing of Freedom,

The clouds they were grey and the autumn winds blew,

And Denise McNair brought the number to two.

The falcon of death was a creature they knew,

And the choirs kept singing of Freedom,

The church it was crowded, but no one could see

That Cynthia Wesley's dark number was three.

Her prayers and her feelings would shame you and me.

And the choirs kept singing of Freedom.

Young Carol Robertson entered the door

And the number her killers had given was four.

She asked for a blessing but asked for no more,

And the choirs kept singing of Freedom.

On Birmingham Sunday a noise shook the ground.

And people all over the earth turned around.

For no one recalled a more cowardly sound.

And the choirs kept singing of Freedom.

The men in the forest they once asked of me,

How many black berries grew in the Blue Sea.

And I asked them right with a tear in my eye.

How many dark ships in the forest?

The Sunday has come and the Sunday has gone.

And I can't do much more than to sing you a song.

I'll sing it so softly, it'll do no one wrong.

And the choirs keep singing of Freedom.

Legal Chronology

Sept. 15, 1963: Dynamite bomb explodes outside Sunday services at Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, killing 11-year-old Denise McNair and 14-year-olds Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson and Addie Mae Collins, and injuring 20 others.

May 13, 1965: FBI memorandum to director J. Edgar Hoover concludes the bombing was the work of former Ku Klux Klansmen Robert E. Chambliss, Bobby Frank Cherry, Herman Frank Cash and Thomas E. Blanton, Jr.

1968: FBI closes its investigation without filing charges.

1971: Alabama Attorney General Bill Baxley reopens investigation.

Nov. 18, 1977: Chambliss convicted on a state murder charge and sentenced to life in prison.

1980: Justice Department report concludes Hoover had blocked prosecution of the Klansmen in 1965.

Oct. 29, 1985: Chambliss dies in prison, still professing his innocence.

1988: Alabama Attorney General Don Siegelman reopens the case, which is closed without action.

1993: Birmingham-area black leaders meet with FBI, agents secretly begin new review of case.

Feb. 7, 1994: Cash dies.

July 1997: Cherry interrogated in Texas; FBI investigation becomes public knowledge.

Oct. 27, 1998: Federal grand jury in Alabama begins hearing evidence.

April 26, 2000: Cherry arrested on charges he molested a former stepdaughter 29 years earlier. He is later extradited to Alabama.

May 17, 2000: Blanton and Cherry surrender on murder indictments returned by grand jury in Birmingham.

April 10, 2001: Judge delays Cherry trial, citing defendant's medical problems, but refuses to dismiss charges against either man.

April 16, 2000: Jury selection to begin in case against Blanton.

May 1, 2001: Blanton convicted

Return to Dudley Randall