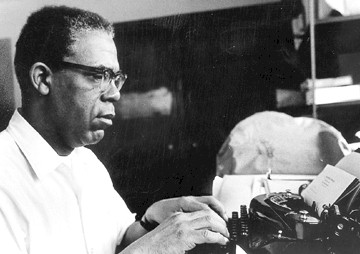

Dudley Randall's Life and Career

Naomi Long Madgett

Poet,

publisher, editor, and founder of Broadside Press. Dudley Randall was born 14 January 1914

in Washington, D.C., but moved to Detroit in 1920. His first published poem appeared

in the Detroit Free Press when he was thirteen. His early reading included English

poets from whom he learned form. He was later influenced by the work of Jean Toomer and

Countee Cullen.

Poet,

publisher, editor, and founder of Broadside Press. Dudley Randall was born 14 January 1914

in Washington, D.C., but moved to Detroit in 1920. His first published poem appeared

in the Detroit Free Press when he was thirteen. His early reading included English

poets from whom he learned form. He was later influenced by the work of Jean Toomer and

Countee Cullen.

His employment in a foundry is recalled in "George" (Poem Counterpoem), written after encountering a once vigorous coworker in a hospital years later. His military service during World War 11 is reflected in such poems as "Coral Atoll" and "Pacific Epitapns"v (More to Remember).

Randall worked in the post office while earning degrees in English and library science (1949 and 1951). For the next five years he was librarian at Morgan State and Lincoln (Mo.) universities, returning to Detroit in 1956 to a position in the Wayne County Federated Library System. After a brief teaching assignment in 1969, he became librarian and poet in residence at the University of Detroit, retiring in 1974.

His interest in Russia, apparent in his translations of poems by Aleksander Pushkin ("I Loved You Once," After the Killing) and Konstantin Simonov ("My Native Land" and "Wait for Me" in A Litany of Friends), was heightened by a visit to the Soviet Union in 1966. His identification with Africa, enhanced by his association with poet Margaret Esse Danner from 1962 to 1964 and study in Ghana in 1970, is evident in such poems as "African Suite" (After the Killing).

When "Ballad of Birmingham," written in response to the 1963 bombing of a church in which four girls were killed, was set to music and recorded, Randall established Broadside Press in 1965, printing the poem on a single sheet to protect his rights. The first collection by the press was Poem Counterpoem (1966) in which he and Danner each thematically matched ten poems on facing pages. Broadside eventually published an anthology, broadsides by other poets, numerous chapbooks, and a series of critical essays. These publications established the reputations of an impressive number of African American poets now well known while providing a platform for many others whose writing was more political than literary.

Following the 1967 riot in Detroit, Randall published Cities Burning (1968), a group of thirteen poems, all but one previously uncollected. This pamphlet, like the first, contains poems selected on the basis of theme and does not follow a chronological development in the author's work. Fourteen love poems appeared in 1970 (Love You), followed by More to Remember (1971), fifty poems written over a thirty-year period on a variety of subjects, and After the Killing (1973), fifteen new poems that comment on such contemporary topics as contradictory attitudes during a period of racial pride and nationalism.

Publication of A Litany of Friends (1981; rpt. 1983) followed several years of suicidal depression that incapacitated Randall and put Broadside Press temporarily at risk. This period of recovery was his most productive, comprising some of his most original--though not necessarily his best--work. Included are eighty-four poems, thirty very recent ones and forty-six previously uncollected.

On the basis of "Detroit Renaissance," published in Corridors magazine in 1980, the mayor of Detroit named Randall poet laureate of that city in 1981.

A distinctive style is difficult to identify in Randall's poetry. In his early poems he was primarily concerned with construction. Many of those in More to Remember are written in such fixed forms as the haiku, triolet, dramatic monologue, and sonnet while others experiment with slant rhyme, indentation, and the blues form. He later concentrated on imagery and phrasing, yet some of his more recent work continues to suggest the styles of other poets. Although many of these move with more freedom, originality, and depth of feeling, and encompass a wider range of themes, others identifiable by printed date demonstrate a return to traditional form.

While Dudley Randall's reputation as a pioneer in independent African American book publishing is secure, he is sure to be remembered for his poems as well, including "Booker T. and W.E.B.," which succinctly summarizes philosophical differences between Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois in a simple dialogue; "Ballad of Birmingham," "Southern Road," and "Souvenirs," all from Poem Counterpoem; "Roses and Revolutions," "Primitives," and "A Different Image" (Cities Burning); "Faces" and "Perspectives" (More to Remember); "The Profile on the Pillow" and "Black Magic" (Love You); "Frederick Douglass and the Slave Breaker" (After the Killing); and "A Poet Is Not a Jukebox" (A Litany of Friends).

See also: A. X. Nicholas, "A Conversation with Dudley Randall," in Homage to Hoyt Fuller, ed. Dudley Randall, 1984, pp. 266-274. R. Baxter Miller, "Dudley Randall," in DLB, vol. 41, Afro-American Poets since 1955, eds. Trudier Harris and Thadious M. Davis, 1985, pp. 265-273.

Betty DeRamus

Midway through funeral services for Detroit poet and publisher Dudley Randall, librarian Malaika Wangara leaped up and started singing, "He was a friend of mine." Her strong-willed alto rose and spread its wings, filling Plymouth United Church of Christ with soaring sweetness.

Wangara was not the only person who lifted her voice during Saturday services for Dudley Randall, founder of the nationally known, Detroit-based Broadside Press.

Poets recited Randall's poems, a musician tinkled bells and squeezed fat, wet drops of the blues from his harmonica and Randall's Kappa Alpha Psi brothers sang their fraternity song. Speakers talked about the man who wore a tie, built his own house from the ground up, stayed married to Vivian Barnett Spencer for 43 years and never quit being kind. They called him a friend, a mentor, an inspiration, a Boy Scout troop leader, a calming influence during the 1967 riot, a Wayne County librarian, a poet-in-residence at University of Detroit and Detroit's poet laureate.

Most of all, people remembered him as the man who built a publishing company that helped lay the foundation for much of the success of today's African-American writers.

"Broadside Press was bigger in terms of impact than just the specific books," said Melba Boyd, a Broadside Press poet and head of Wayne State University's Africana Studies department.

"As an independent press that was successful but small compared to mainstream (publishers), it opened up the literary canon, and now mainstream publishers began publishing poetry and black writers and other minority writers. It ... changed the whole character of American literature."

Randall was the other Berry Gordy, the one who never left the west side of Detroit, never made millions and never became a glitter-sprinkled celebrity. Yet he, too, beamed black voices around the world, receiving a Lifetime Achievement Award in 1996 from the National Endowment for the Arts.

His stars weren't slinky singers or coordinated crooners. Randall showcased previously unpublished poets and national figures such as Nikki Giovanni, Sonia Sanchez, LeRoi Jones, Alice Walker and Haki Madhubuti.

Pulitzer-prize-winning poet Gwendolyn Brooks left Harper and Row to become a Broadside poet. And Audre Lorde's 1973 Broadside book, From a Land Where Other People Live, was nominated for a National Book Award.

Like Berry Gordy, who boxed and worked on an assembly line before founding Motown, Randall didn't become a legend overnight. He worked for Ford, and labored at the post office while earning degrees in English and library science.

According to the often-told story, Gordy set up Motown with an $800 loan from his family. Randall began his publishing career with $12.

However, Randall became a publisher by chance. In response to a 1963 church bombing in Alabama, he wrote"The Ballad of Birmingham," and his poem was set to music and recorded by a folk singer. To protect his rights, Randall had it printed on a single sheet, or broadside, in 1965. That was the start of Broadside Press.

The Press grew "by hunches, intuitions, trial and error," Randall once wrote, until it had published 90 titles of poetry and had printed 500,000 books. In his spare bedroom, Randall licked stamps and envelopes, packed books, read manuscripts, wrote ads and planned and designed books.

Dudley Randall, 86, died Aug. 5, but speakers at the poet's funeral -- which he planned 15 years ago -- said his influence remains strong.

"I am the man I am today in part because of Dudley Randall," said Madhubuti, poet and founder of Chicago's Third World Press. "I ... stayed in his house. He taught me what was possible. (Without black poetry) I had about as much promise as a raindrop in the desert."

"He was my friend and colleague in the community of poets who flourished during the 1950s and 1960s in Detroit," added Naomi Long Madgett, poet and founder of Lotus Press.

"Through Lotus Press I followed in his footsteps and brought out his last book (A Litany of Friends) in 1981. The song may be ended, but the legacy lives on."

from The Detroit News (8/15/00). Online Source

Return to Dudley Randall