Edwin Rolfe: Biography

Rolfe was born

Solomon Fishman; his parents Nathan and Bertha emmigrated from

Jewish communities in Russia early in the century and met in

Philadelphia, where they lived for the first few years of Rolfe's

life before moving to New York. Rolfe began using pen names in

high school, used the name "Edwin Rolfe" on some

publications in the late 1920s, and by the early 1930s had

effectively become Edwin Rolfe. Changing his name was a gesture

that signalled at once his chosen identity as a writer and his

conscious decision to commit himself to political activism.

Rolfe was born

Solomon Fishman; his parents Nathan and Bertha emmigrated from

Jewish communities in Russia early in the century and met in

Philadelphia, where they lived for the first few years of Rolfe's

life before moving to New York. Rolfe began using pen names in

high school, used the name "Edwin Rolfe" on some

publications in the late 1920s, and by the early 1930s had

effectively become Edwin Rolfe. Changing his name was a gesture

that signalled at once his chosen identity as a writer and his

conscious decision to commit himself to political activism.

His father was a socialist, later a member of the Lovestonite faction of the Communist Pary, and an official of a union local in New York. His mother was active in the birth control movement, pitched in during the famous 1913 silk workers strike in Paterson, New Jersey, and later joined the Communist Party. At the flat on Coney Island in New York where they lived for much of Rolfe's childhood, they let rooms to other people to help cover the rent; one such tenant was a red-headed Wobbly from the West—a member of our most irreverent, disruptive, and populist union, the Industrial Workers of the World—who used to give Rolfe and his younger brother Bern rides on his motorcycle and tell them stories of I. W. W. organizing. Rolfe himself joined the Party (and was assigned to the Young Communist League) in 1925, when he was fifteen. When he published his first poem in The Daily Worker in 1927, "The Ballad of the Subway Digger," it was a newspaper he already knew well at home.

After working intermittently in the already selectively depressed New York economy of the late 1920s, Rolfe wanted relief from the city and a chance to read and write in a less interrupted way. He was also ready to break with the Communist Party, some of whose functionaries neither then nor later did he find sympathetic figures. Left politics, moreover, had been frequently disputatious during the 1920s; indeed, in one such dispute his parents had aligned themselves with different groups, and thus the political conflicts of the period also played themselves out in Rolfe's family. In the fall of 1929 he quit the Party and left New York to enroll in the Experimental College at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. As his advisors noted, he retained strong loyalties to the working classes, but for most of the next year he avoided politics and instead read widely and wrote relatively nonpolitical poems, including three written in 1929 or 1930 and published in Pagany in 1932. As the Depression deepened, however, he was drawn to politics again and left Wisconsin in the middle of his second year there.

Rolfe rejoined the Party in New York and, after a variety of

temporary jobs, began working full time at The Daily Worker.

This was the period when the Party was beginning to move toward

becoming part of a mass movement. In the midst of massive

unemployment, vast dislocation and widespread hunger—and

little faith that capitalism would recover—many here and in

Europe were radicalized. For a time revolutionary social and

political change seemed possible. Dozens of radical journals

sprung up, not only in large cities but also in small towns and

rural communities across the country. Radical theater drew  audiences from

all classes. Political art appeared in public places. Despite

considerable suffering, the mid-1930s were thus a heady time on

the Left. Much of the poetry of the period combines sharp social

critique with a sense of revolutionary expectation. More than

simply reflecting the times, however, the "proletarian"

poetry of revolution sought to define a new politics, to suggest

subject positions within it, and to help bring about the changes

it evoked. Far from a solitary romantic vocation, moreover, 1930s

political poetry is a form of collaborative rhetorical action, as

poets respond to one another by ringing changes on similar

revolutionary themes and metaphors.

audiences from

all classes. Political art appeared in public places. Despite

considerable suffering, the mid-1930s were thus a heady time on

the Left. Much of the poetry of the period combines sharp social

critique with a sense of revolutionary expectation. More than

simply reflecting the times, however, the "proletarian"

poetry of revolution sought to define a new politics, to suggest

subject positions within it, and to help bring about the changes

it evoked. Far from a solitary romantic vocation, moreover, 1930s

political poetry is a form of collaborative rhetorical action, as

poets respond to one another by ringing changes on similar

revolutionary themes and metaphors.

Rolfe published his first book of poems, To My Contemporaries, in 1936, the same year he married Mary Wolfe. A few months later the Spanish Civil War began, and soon Rolfe's thoughts turned to Spain. No cause in the 1930s had quite the power of the international effort to come to the defense of the Spanish Republic. From the outset, when a group of right-wing army officers revolted against the elected popular front coalition government in July of 1936, it was clear that Spain was to be at once the real and symbolic site of the growing struggle between democracy and fascism. The Comintern (Communist International) decided to organize groups of international volunteers to help defend the Spanish Republic. Rolfe joined these International Brigades in the spring of 1937. Once in Spain he was assigned to edit Volunteer for Liberty, the English language magazine of the volunteers, in Madrid. That he did until joining the troops in the field in the spring of 1938. When the Americans were brought out of battle that fall, Rolfe's wife Mary joined him in Barcelona.

When the Rolfes returned from Spain in January of 1939 the

Spanish cause was already under attack. Martin Dies had begun

congressional hearings on Communist activity, and people who had

worked on Spain's behalf were under suspicion. Rolfe's  brother Bern, a

Federal employee who had raised funds for Loyalist Spain and was

secretly a Communist Party member, was among those who came under

scrutiny, though he would keep his government job for now. In any

case, it was clear that the Left was in for some difficulty,

though it seemed then that the Left would be strong enough to

defend itself successfully. Still, it was deeply disturbing to

watch heroes of the war like Lincoln Battalion commander Milt

Wolff harassed in front of the House UnAmerican Activities

Committee. For much of the next two years, then, Spain remained

at the center of Rolfe's life. He signed a contract to write a

history of the Lincolns, and late in 1939 Random House brought it

out under the title The Lincoln Battalion.

brother Bern, a

Federal employee who had raised funds for Loyalist Spain and was

secretly a Communist Party member, was among those who came under

scrutiny, though he would keep his government job for now. In any

case, it was clear that the Left was in for some difficulty,

though it seemed then that the Left would be strong enough to

defend itself successfully. Still, it was deeply disturbing to

watch heroes of the war like Lincoln Battalion commander Milt

Wolff harassed in front of the House UnAmerican Activities

Committee. For much of the next two years, then, Spain remained

at the center of Rolfe's life. He signed a contract to write a

history of the Lincolns, and late in 1939 Random House brought it

out under the title The Lincoln Battalion.

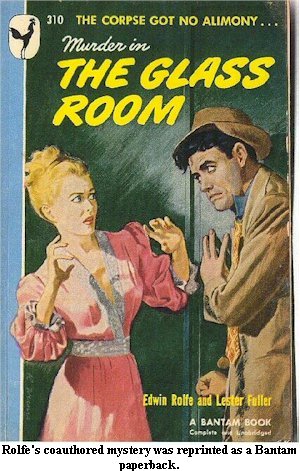

Thereafter Rolfe worked for TASS, the Soviet news agency, for several years. He was drafted in 1943, at which point Mary accepted a job in Los Angeles. Rolfe joined her there, published a mystery novel (The Glass Room), and found occasional work on the fringes of the film industry. His Hollywood work came to an end in 1947 when HUAC arrived in Los Angeles and Rolfe was blacklisted. For the rest of his life both he and Mary were taken up in the struggle against McCarthyism. Rolfe himself would write the strongest body of anti-McCarthy poems of any American poet. He died of a heart attack in 1954.

By Cary Nelson. Copyright © 1999 Cary Nelson.

Return to Edwin Rolfe