A Review of Rolfe's Collected Poems

By Bernard Knox

The University of Illinois Press, which published Milton

Wolff's Spanish Civil War novel Another Hill, reviewed in the last issue, has also

launched a project entitled The American Poetry Recovery Series, which "will

consist of collections and anthologies by poets whose work has not been made part of the

traditional literary canon, including labor poets, feminist and minority poets, and socialist and anarchist poets." The first

volume in the series collects the poems of Edwin Rolfe, who fought in the Lincoln

Battalion in Spain. It is a reprint of the three collections of his poetry printed in

1936, 1951, and (posthumously) 1955, together with a great many uncollected and

unpublished poems, but excluding, except for a small selection, poems written "before

Rolfe matured as a writer." It is an impressive body of work, set in its historical,

literary, and biographical context by Cary Nelson's masterly introduction.

minority poets, and socialist and anarchist poets." The first

volume in the series collects the poems of Edwin Rolfe, who fought in the Lincoln

Battalion in Spain. It is a reprint of the three collections of his poetry printed in

1936, 1951, and (posthumously) 1955, together with a great many uncollected and

unpublished poems, but excluding, except for a small selection, poems written "before

Rolfe matured as a writer." It is an impressive body of work, set in its historical,

literary, and biographical context by Cary Nelson's masterly introduction.

Born Solomon Fishman to Russian immigrant parents in 1909, he began writing when very young. By the age of fifteen he had published cartoons in the Daily Worker as well as stories, poems, and reviews in the Comet, the literary magazine of the New Utrecht High School in Brooklyn. In 1926 he "ran into difficulty in a trigonometry class" and was prohibited from publishing in the magazine until his grades improved. He began submitting contributions nevertheless, under "a series of playful pseudonyms"1 such as W. Tell and R. Hood, and in 1927 signed a review in the Daily Worker with the name Edwin Rolfe, which became his name in print and in real life from then on.

His life was a hard one. Writing could not earn him a living and he moved through a succession of temporary jobs--dishwasher in a restaurant, helper in a fruit store, punch press operator, laborer digging the subway, printing signs (at five to seven dollars a week)--interrupted by a year at the University of Wisconsin. Back in New York he lived from hand to mouth, publishing poems and reviews until in 1933 he was given the job of feature editor on the Daily Worker four hours a day at $10 a week. In 1936 his first poetry collection, To My Contemporaries, was published by the Dynamo Press.

The poems, though often technically interesting, are thematically fairly predictable Communist poems of the Depression era; typical titles are "Georgia Nightmare," "Homage to Karl Marx." "Witness at Leipzig," "Unit Meeting," and "These Men Are Revolution." Yet sometimes they create, with intense feeling and exact detail the misery of those Depression winters, the days when "the breath of homeless men/freezes on restaurant window panes--men seeking/the sight of rare food/before the head is lowered into the upturned collar/and the shoulders hunched and the shuffling feet/move away slowly, slowly disappear/into a darkened street." Spain transformed his poetry. The fervent advocacy is, if anything, heightened, but the lines now have a plangent, sometimes heart-breaking, lyricism.

He left for Spain in June 1937 and began training at Tarazona, but late in July was asked if he would like to take over the editorship of the Volunteer for Liberty, the English-language magazine of the Brigades, an assignment for which his experience as a feature editor for the Daily Worker in New York made him the obvious choice. He said no, but was ordered to take the job and move to Madrid. From his base there he made frequent visits to the American battalion at the front and bitterly regretted his noncombatant status, even though much of the time he worked in Madrid he was seriously ill. In March 1938, together with the Volunteer, he moved from Madrid to Barcelona, a city now under constant bombardment by Italian planes. When in April all able-bodied men were directed to report for front-line duty, Rolfe did so even though his position exempted him from the order. He took part in the offensive across the Ebro and in the disorganized retreat that followed as Franco counter-attacked in irresistible force. Rolfe had had his baptism of fire at last, and one of his friends remarked years later that "after Spain things about his personal life that Rolfe would once have talked about openly he now seemed to save for his poetry."2

In most of the poems he wrote then and in later years, the memory of Spain haunts the lines even where it is not mentioned. But it is usually explicit, as in the "Elegia" for Madrid, written ten years after the end of the war:

Madrid, if ever I forget you,

may my right hand lose its human cunning...

And if I die before I can return to you,

or you, in fullest freedom, are restored to us,

my sons will love you as their father did

Madrid Madrid Madrid

It is explicit too in the "Elegy for Our Dead," where he uses the alliterative technique of Anglo-Saxon verse:

There is a place where, wisdom won, right recorded,

men move beautifully, striding across fields...

where lie, nurturing all these

fields, my friends in death.

...

Honor for them in this lies: that theirs is no special

strange plot of alien earth. Men of all lands here

lie side by side, at peace now after the crucial

torture of combat, bullet and bayonet gone, fear

conquered forever...

And in "First Love," the title poem of the volume, he writes among young men training for war in Texas, but thinks of another war.

I am eager to enter it, eager to end it.

Perhaps this one will be the last one.

...

But my heart is forever captive of that other war

that taught me first the meaning of peace and of comradeship

and always I think of my friend who amid the apparition of bombs

saw on the lyric lake the single perfect swan.

These poems had a strange publishing history. "Elegy for our Dead" first appeared in the Volunteer for Liberty in Spain in January 1938; it was reprinted in The New Republic and the Daily Worker. "First Love" appeared in Yank: The Army Weekly in September 1945. But by 1948, when "Elegia" was written, "there was literally no place to publish it. Even the Communist Party-supported Masses and Mainstream refused it, partly because the biblical allusions offended the editors; religion, after all, could only be the opiate of the people." Rolfe sent a copy to Hemingway, who wrote back: "Your fucking poem made me cry and I have only cried maybe four times in my life...."

Rolfe also gave a copy to a Spanish exile, José Rubia Barcia, who translated it into Spanish and sent it to Luis Buñuel in Mexico City. There another Spanish exile, the printer and poet Manuel Altolaguirre, issued it in the form of a pamphlet and the poem was recited at gatherings of Spanish exiles in Mexico, Argentina, and Chile. It finally appeared in print in English, together with the other two, in 1951, when Rolfe published his second collection, First Love, himself. In September of that year he sent out circulars inviting subscribers to pay the costs of printing and binding, for all the world like Alexander Pope collecting subscriptions for his translation of the Iliad--"the Subscribers are to pay two Guineas in hand, advancing one in regard of the Expense the Undertaker must be at..."3 Two hundred seventy-five copies, at $2.75 each, were issued under the imprint of the Larry Edmunds Bookshop, and by the end of January all were sold. But only two reviews appeared, one by Aaron Kramer in the National Guardian and the other by Rolfe Humphries in The Nation.

The last poems reflect the bitterness of the years of persecution, the time of informers, as in "Little Ballad for Americans 1954," written one month before his death of a heart attack.

Housewife, housewife, never trust your neighbor

A chance remark may boomerang to five years at hard labor.

Student, student, keep mouth shut and brain spry--

Your best friend Dick Merriwell's employed by the F.B.I.

But they often hark back to Spain as in "1949 (After Reading a News Item)":

His first official act was to bless

The planes that bombed their Barcelona home.

Ten years have passed. Today his Holiness

Welcomes the Catalan orphans into Rome.

But in the poem that gives the last volume its title he creates a moving lyric that has little to do with politics:

Permit me refuge in a region of your brain:

carry and resurrect me, whatever path you take,

as a ship creates its own unending wake

or as rails define direction in a train...

With the publication of these two volumes the University of Illinois Press has done a notable service to American poetry.

Notes:

1. Edwin Rolfe: A Biographical Essay, p. 7. The guide contains some interesting photographs and facsimiles and extracts from letters of, among others, Ernest Hemingway and Albert Maltz. (back to text)

2.Edwin Rolfe: A Biographical Essay, p. 37. (back to text)

3. Alexander Pope, The Iliad of Homer, edited by Maynard Mack, et al. (Yale University Press, 1967), p. xxxvi, no. 5. (back to text)

from The New York Review of Books, Volume XLI, Number 21. (December 22, 1994) p. 18.

Edward J. Brunner

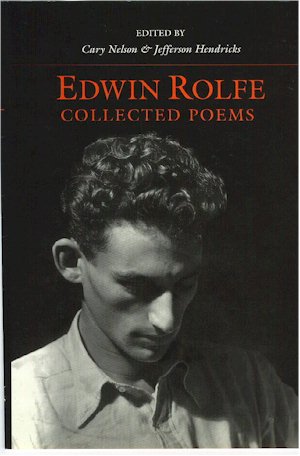

Edwin Rolfe: Collected Poems. Edited by Cary Nelson and Jefferson Hendricks. Urbana: U of Illinois P, 1993. 337 pp. $34.95.

Edwin Rolfe. Trees Became Torches: Selected Poems. Edited by Cary Nelson and Jefferson Hendricks. Urbana: U of Illinois P, 1995. 152 pp. $13.95.

Before Cary Nelson and Jefferson Hendricks assembled the 1993 Collected Poems, Edwin Rolfe may have been the most obscure of those poets who had been admired in the 1930s for their revolutionary spirit. He could be glimpsed, briefly but affectionately, in a memoir that New Masses editor Joseph North used as a foreword to an anthology of the "rebel thirties." Rolfe's History of the Lincoln Brigade (1939) narrated the Spanish Civil War from an eyewitness point of view and kept his name alive as a spokesperson for the left. Even so, few recalled his first book, To My Contemporaries (1936) except as an example of the "Dynamo" group of poets--writers for whom (in Walter Kalaidjian's words) "machinery signified the new powers of industrial production as well as capital's contradictory relation to labor" (153). And fewer still were even aware of his two later collections, the by-subscription-only First Love and Other Poems, which Rolfe himself issued in 1951 (it was limited to 375 copies), and the posthumously assembled Permit Me Refuge, which Thomas McGrath edited in 1955, a year after a heart attack had claimed Rolfe at the age of 45. This once unobtainable material has been handsomely restored by Nelson and Hendricks in the inaugural volume of the American Poetry Recovery Series --three collections plus a generous sheaf of uncollected and unpublished poems, painstakingly annotated with an extensive introduction -- and now there is a collection of selected poems, Trees Became Torches, a reader's edition that presents about half the poems in five useful thematic clusters.

An overview of Rolfe's entire career reveals how he might have been especially prone to slide into unjustified obscurity. However you set out to peg him, he never quite fits in. In the 1930s, in the aftermath of World War II, in the first half of the 1950s, he is always out of place. He even escapes the profile of the '30s poet, the category into which he had been previously dropped. For one thing, he continued to write politically aware verse long after the decade had passed. For another, he was never particularly committed to a distinct ideological line--he was in fact "punished" at various times by fellow radicals for supposed transgressions. His "Elegia" (1948), a lament for all that had been lost after the Spanish Civil War (including its temporary sense of international solidarity), was rejected by Masses and Mainstream, whose editors were offended by the poem's soft handling of religion. Despite such rebuffs, Rolfe always remained loyal to social concerns. Unlike many in the 1930s who had turned to politics only after the economy had collapsed, Rolfe grew up in a political environment. His Russian Jewish immigrant parents were socialists, labor organizers, and Communist Party members. (As a prelude to their divorce, they aligned themselves with different party factions.) The political was as deeply embedded in his background as the liturgical was in T. S. Eliot's. What was natural was that he would sell his first poems (in the 1920s) to the Daily Worker and the New Masses, publications with which he was very familiar from his home life. What was unnatural was a year's break for college in Madison, Wisconsin. While he there learned to write poems that began "There's still some life left in an old red barn / half-hidden behind a rolling swell of earth" (268), he never managed to see Wisconsin--the sides of the barn "sag / like empty faces in Milwaukee flops"-- and he returned soon enough to the New York urban milieu he had never quite left.

Rolfe’s poems of the 1930s testify to the ease with which he moved in revolutionary circles and regarded himself as a witness to history. But they are also sophisticated technical exercises. Few volumes from Sol Funaroff's Dynamo Press contained sonnets, but Rolfe included three, one of them rhyming perfectly. As a "Dynamo" poet, Rolfe was supposed to incorporate the machine into his text, but few examples of machinery appear in any of his poems. Most are set against an urban backdrop, though even that turns unerringly literary. He sketches the unemployed along the East River--

the eyes

are focused from the river

among the floating garbage

that other men fish for,

their hands around poles

almost in prayer—

wanting to live. . .

--and elaborately echoes T. S. Eliot, materially repositioning his Fisher King from alongside the Thames. Rolfe is always reaching across generations to speak to other poets who form a community of the wise. Perhaps from Hart Crane--a poet whose work he quotes from (the title of one poem "More than Flesh to Fathom" is from a line in The Bridge) or evokes ("Permit me refuge," the opening phrase of "Bon Voyage," recalls "Permit me voyage" from "Voyages III")--he derived the conviction that the lyric and the analytic are not so much differentials as mutually attracting poles.

Rolfe could include the lyrical in his essentially analytic texts because social concerns, not ideological debates, were what held his interest. Not surprisingly, the event that drew him out as nothing else ever would was the 1937-38 Spanish Civil War, so clearly a communal effort, a selfless gathering of volunteers from all nations. His Spanish Civil War poems perform transformations in which nobility and strength emerge from a testing situation. They are his first mature work, even as the strands show that still attach it to his earlier political verse are still visible. The phrase "trees became torches" describes the aftermath of a bombing raid that, instead of shattering morale, only motivates a greater resolve, as "the trees became torches / lighting the avenues / where lovers huddled in terror / who would be lovers no longer." It is as though the slogans that had previously existed in 1930s revolutionary poetry were turning into objective correlatives right before Rolfe's eyes.

But these original poems never really came before any large public. The book in which they were to appear set out to contrast the difference between the Spanish Civil War, with its volunteers from all nations, and World War II, with its conscripts arrayed against nation-states (its working title since 1944 had been Two Wars). "We must remember cleanly why we fought," he began one poem (dated 1939), and in another (dated 1945) he used the occasion of war's end to call for a renewed struggle on a higher plane. The manuscript, retitled First Love and Other Poems, circulated unsuccessfully among publishers. No one was eager, after World War II, for another call to arms. The poetry about war that succeeded in the late 1940s, like John Ciardi's remarkable Other Skies (1947), depicted war itself as the enemy. Of immediate danger to the soldier was the impersonal and dehumanizing military bureaucracy. Consequently, in Ciardi's lines individuals were always placing their mark on things, hoping to stamp a moment or a place as their own and so resist erasure. In his most inspired poems, their gestures are at once defiant and helpless and nostalgic--painting pin-up girls on B-29s. But they are rarely noble, at least not intentionally. And while Ciardi made it clear he planned to leave the war entirely behind him and pursue a vision of domestic bliss and upward mobility, Rolfe made it equally clear that he would be drawing lessons from history, using one was to measure the other. "Elegia," his homage to Madrid and the international spirit, ends with his vow not to forget that extraordinary communal moment. But after 1945, it was forgetfulness that people wanted to pursue.

Rolfe registers such cultural amnesia in "A Poem to Delight My Friends Who Laugh at Science Fiction" (1953). It depicts the postwar world as a place where horrifying events can occur -- the mass suicide of creatures, of humans, even of machines -- but without anyone taking notice. At the poem's end, only soldiers are left to wander in a ruined landscape, "like drunken stars in their shrinking orbits / round and round and round and round." The text is an iroinc performance, a negative staging designed to alert us to the way that manufactured images of catastrophe, such as those produced by the movies, encourage an audience to become oblivious. We have committed suicide when we yield to ominous events like those Rolfe records and do not even murmur a protest. Rolfe had been in Hollywood since 1944, scripting screenplays (one of which was entitled "Destination Moon") as well as footage for documentaries (he wrote the text for Muscle Beach, much honored in 1951); moreover, he co-authored a thriller that had been optioned as a vehicle for Bogart and Bacall. His poetic comment on science fiction was, then, an insider's critique of the industry. Yet ironically enough, "A Poem to Delight" fulfilled its title's promise: it was the single runaway hit of Rolfe's career as a poet, accepted by Poetry magazine, reappearing almost at once in two mass-market anthologies in 1953 and 1955, then later in three somewhat specialized collections. To Rolfe, its popularity must have been a curiously bitter triumph, for it would only have underscored the ease with which, in this era, even the most disturbing images could be consumed.

Thomas McGrath’s Foreword to Rolfe's posthumous volume of 1955 describes these last poems as "the first things in the beginning of his best period." These poems of the 1950s are both new and recognizably Rolfe's -- carefully cadenced in slow, almost sluggish rhythms that suggest thought occurring within pain, under a weight of immense sorrow. Writing as the homecoming Ulysses in a dedicatory poem, he speaks out of a knowledge that is hard-won: "And if, all my Penelopes, there's little you recognize, / blame Time, not me; nor strain your skeptic eyes. // It’s the world that's altered." Like a survivor from a conflict that has become remote, Rolfe anticipates our naive responses and must brush them wearily away. How many poets became little Penelopes in this domestic time.... Now history enters the poems as a palpable weight as Rolfe shifts voices, sometimes to brilliant effect. He begins a sonnet, one of the many he composed throughout his career, by describing in the octet a person who has grown exhausted with the "dark forces/ phalanxed against him," and we think of the McCarthy hearings and the subpoenas to appear before HUAC that must have been on Rolfe's mind. But the sestet swerves and expands, and suddenly Rolfe is contemplating the simple man, the soldier "who never clearly saw the threatening shapes yet fought / his complex enemies." It was his example "who taught us, who talk so glibly, / what the world's true shape should be like." We have come a long way from the initial narrow view; we are artfully repositioned within a larger battle, one without petty ends, and our own talk has been opened to question for its glib assumptions. This dark voice of history, though, was utterly out of fashion in the ahistoricizing 1950s.

Rolfe began his career by aiming to write the popular poem whose slogans would ignite feeling. What he moved toward, what he ended doing, was quite different but far more impressive: in the midst of barbarity, he discerns (and sometimes performs and always preserves) the civilizing gesture, the transforming twist that recovers a value. He ends his 1943 "First Love," one of the first poems in which he writes with history as a weight that burdens him down: "And always I think of my friend wait amid the apparition of bombs / saw on the lyric lake the single perfect swan." Violence is apparitional, transient; friendship endures in memory where it associates with beauty and perfection. (Strikingly, History of the Lincoln Brigade is organized around a similar rhythm: Rolfe interrupts the narrative of the war continually by importing autobiographical sketches of the volunteers, most of whom sacrificed their lives heroically; their memorialization in prose ephemeralizes military conquests.)

So often, indeed, does Rolfe deal with an impossible circumstance attempting to redeem it through an act of transcendence or a gesture of forgiveness, that it may be that for him the great poetic theme was betrayal. Betrayal is nothing like disappointment: betrayal rends the social fabic and cries out for a counter-action that will, even in a small way, restore us to order. It prompts an essentially selfless response. As early as his 1936 collection, in a sonnet entitled "Definition" (its text, incidently, reprinted almost as many times as "A Poem to Delgiht"), he acknowledges that others have betrayed the spirit of comradeship by acting in ways that are "mean, underhanded, lacking all attributes / real men desire." But he will respond by reinvesting the idea of the comrade with dignity, recovering it from misuse; that recuperation is notably figured as a mark of genuine power--what "real men desire" (in the atavistic vocabulary of the times)--not losing but winning, yet without a blatant sense of victory over another. Rolfe had ample opportunity to exercise that selflessness in the witch-hunting 1950s. "Night World," from the last volume, nightmarishly suggests the confusions of the time, even as Rolfe's redemptive gesture recurs. Its first stanza locates two lovers tossing restlessly on their bed. Why are they so unquiet? Outside their "bridal catacomb the moon / rides the cloud stallions, angry, bucking / the vindictive heavens." The moon is distraught because it wears the reputation of the treasonous--"numberless children still alive" will "deem him enemy, remembering / his guidance of the plummeting plane." But the moon, we are meant to protest, was innocent--not responsible for how others used its light. Yet somehow innocence has become associated with guilt, and the moon is now thought of as betraying "slumbers, mothers, dreams." In Rolfe's exceedingly intricate close, the moon dissociates itself, turning inward, away from the earth, becoming " a lone dream-misted eye / [that] rides its own beam to the most distant star." Elaborately encoded, this is, of course, Rolfe's own complex response to betrayal. Characteristically, it ends not in an explosion of anger but in an implosion that allocates resources elsewhere (the moon displaces its light to a remote star). Up to the end, even when he was stung by betrayal, Rolfe remained responsible, devoted to higher concerns.

Turning away from a devastated present to recover a deeper, now lost value becomes Rolfe's exemplary task in his final poems. The ending of his deeply moving "Bon Voyage" is a signature of this period:

Permit my memory refuge: but not the recent years

when grains of dross obscured the bars of truth.

Delve deeper back in years to your first youth,

passionate, clean, untarnished by small fears.And if your conscience truly bears my memory,

rekindle if you can the dying candle-light:

let the wake not lose its contour, nor the bright

reflected sun waver as the rails glide by.My wake and rail attend you, welded and wed,

through the blind tunnels of the years ahead.

Few voices so acutely register the loss experienced in these years when the bright dreams of social justice were virtually obliterated. As he says at the close of "Mystery (II)," who could have imagined the story would end in this way, "the lovely virgin with the dazzling hair won by the diseased roué / and all our golden Tomorrows wrecked on the boneyard of Today?" But that long-accepted story of the twentieth century is being rewritten by new literary scholars at this very moment. (The second edition of the Heath Anthology of American Literature [1994] includes a selection of Rolfe poems, and even the fourth edition of the Norton Anthology of American Literature [1994] presents for the first time the work of "Dynamo" poet Genevieve Taggard along with Muriel Rukeyser.) When that history has been revised--and no doubt continuing volumes in the University of Illinois Press American Poetry Recovery Series will hasten its revision--Rolfe's voice, eloquent and beguiling and exact, will effectively challenge his contemporaries.

Return to Edwin Rolfe