Black War: The Destruction of the Tasmanian Aborigines

Runko Rashidi

To many, the mention of Tasmania evokes humorous recollections of the Tasmanian devil--the voracious marsupial popularized in American cartoons. Tasmania is an island slightly larger in size than West Virginia, and is located two-hundred miles off Australia's southeast coast. The aboriginal inhabitants of the island were Black people who probably went there by crossing an ancient land bridge that connected Tasmania to the continent of Australia.

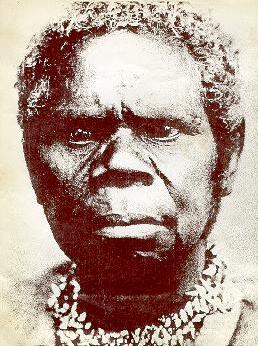

The Black aborigines of Tasmania were marked by tightly curled hair with skin complexions ranging from black to reddish-brown. They were relatively short in stature with little body fat. They were the indigenous people of Tasmania and their arrival there began at least 35,000 years ago. With the passage of time, the gradual rising of the sea level submerged the Australian-Tasmanian land bridge and the Black aborigines of Tasmania experienced more than 10,000 years of solitude and physical isolation from the rest of the world--the longest period of isolation in human history.

It is our great misfortune that the Black people of Tasmania bequeathed no written

histories. We do not know that they called themselves or what they named their land. All

we really have are minute fragments, bits of evidence, and the records and documents of

Europeans who began coming to the island in 1642.

THE BLACK FAMILY IN TASMANIA

The Tasmanian aborigines were hunter-gatherers with an exceptionally basic technology. The Tasmanians made only a few types of simple stone and wooden tools. They lacked agriculture, livestock, pottery, and bows and arrows.

The Black family in Tasmania was a highly organized one--its form and substance directed by custom. A man joined with a woman in marriage and formed a social partnership with her. It would appear that such marriages were usually designed by the parents--but this is something about which very little is actually known. The married couple seems to have remained together throughout the course of their lives, and only in rare cases did a man have more than one wife at the same time. Their children were not only well cared for, but were treated with great affection. Elders were cared for by the the family, and children were kept at the breast for longer than is usual in child care among Europeans.

THE BEGINNING OF THE END OF THE BLACKS

The isolation of Tasmania's Black aborigines ended in 1642 with the arrival and intrusion of the first Europeans. Abel Jansen Tasman, the Dutch navigator after whom the island is named, anchored off the Tasmanian coast in early December, 1642. Tasman named the island Van Diemen's land, after Anthony Van Diemen--the governor-general of the Dutch East India Company. The island continued to be called Van Diemen's Land until 1855.

On March 5, 1772, a French expedition led by Nicholas Marion du Fresne landed on the island. Within a few hours his sailors had shot several Aborigines. On January 28, 1777, the British landed on the island. Following coastal New South Wales in Australia, Tasmania was established as a British convict settlement in 1803. These convicts had been harshly traumatized and were exceptionally brutal. In addition to soldiers, administrators, and missionaries, eventually more than 65,000 men and women convicts were settled in Tasmania. A glaringly inefficient penal system allowed such convicts to escape into the Tasmanian hinterland where they exercised the full measure of their blood-lust and brutality upon the island's Black occupants. According to social historian Clive Turnbull, the activities of these criminals would soon include the "shooting, bashing out brains, burning alive, and slaughter of Aborigines for dogs' meat."

PART 2

TASMANIAN DEVILS IN HUMAN FORM

As early as 1804 the British began to slaughter, kidnap and enslave the Black people of Tasmania. The colonial government itself was not even inclined to consider the aboriginal Tasmanians as full human beings, and scholars began to discuss civilization as a unilinear process with White people at the top and Black people at the bottom. To the Europeans of Tasmania the Blacks were an entity fit only to be exploited in the most sadistic of manners--a sadism that staggers the imagination and violates all human morality. As UCLA professor, Jared Diamond, recorded:

"Tactics for hunting down Tasmanians included riding out on horseback to shoot them, setting out steel traps to catch them, and putting out poison flour where they might find and eat it. Sheperds cut off the penis and testicles of aboriginal men, to watch the men run a few yards before dying. At a hill christened Mount Victory, settlers slaughtered 30 Tasmanians and threw their bodies over a cliff. One party of police killed 70 Tasmanians and dashed out the children's brains."

Such vile and animalistic behavior on the part of the White settlers of Tasmania was the rule rather than the exception. In spite of their wanton cruelty, however, punishment in Tasmania was exceedingly rare for the Whites, although occasionally Whites were sentenced for crimes against Blacks. For example, there is an account of a man who was flogged for exhibiting the ears and other body parts of a Black boy that he had mutilated alive. We hear of another European punished for cutting off the little finger of an Aborigine and using it as a tobacco stopper. Twenty-five lashes were stipulated for Europeans convicted of tying aboriginal "Tasmanian women to logs and burning them with firebrands, or forcing a woman to wear the head of her freshly murdered husband on a string around her neck."

Not a single European, however, was ever punished for the murder of Tasmanian Aborigines. Europeans thought nothing of tying Black men to trees and using them for target practice. Black women were kidnapped, chained and exploited as sexual slaves. White convicts regularly hunted Black people for sport, casually shooting, spearing or clubbing the men to death, torturing and raping the women, and roasting Black infants alive. As historian, James Morris, graphically noted:

"We hear of children kidnapped as pets or servants, of a woman chained up like an animal in a sheperd's hut, of men castrated to keep them off their own women. In one foray seventy aborigines were killed, the men shot, the women and children dragged from crevices in the rocks to have their brains dashed out. A man called Carrotts, desiring a native woman, decapitated her husband, hung his head around her neck and drove her home to his shack."

PART 3

THE BLACK WAR

"The Black War of Van Diemen's Land" was the name of the official campaign of terror directed against the Black people of Tasmania. Between 1803 and 1830 the Black aborigines of Tasmania were reduced from an estimated five-thousand people to less than seventy-five. An article published December 1, 1826 in the Tasmanian Colonial Times declared that:

"We make no pompous display of Philanthropy. The Government must remove the natives--if not, they will be hunted down like wild beasts and destroyed!"

With the declaration of martial law in November 1828, Whites were authorized to kill Blacks on sight. Although the Blacks offered a heroic resistance, the wooden clubs and sharpened sticks of the Aborigines were no match against the firepower, ruthlessness, and savagery exercised by the Europeans against them. In time, a bounty was declared on Blacks, and "Black catching," as it was called, soon became a big business; five pounds for each adult Aborigine, two pounds for each child. After considering proposals to capture them for sale as slaves, poison or trap them, or hunt them with dogs, the government settled on continued bounties and the use of mounted police.

After the Black War, for political expediency, the status of the Blacks, who were no longer regarded as a physical threat, was reduced to that of a nuisance and a bother, and with loud and pious exclamations that it was for the benefit of the Blacks themselves, the remainder of the Aborigines were rounded up and placed in concentration camps.

In 1830 George Augustus Robinson, a Christian missionary, was hired to round up the remaining Tasmanian Blacks and take them to Flinders Island, thirty miles away. Many of Robinson's captives died along the way. By 1843 only fifty survived. Jared Diamond recorded that:

"On Flinders Island Robinson was determined to civilize and Christianize the survivors. His settlement--at a windy site with little fresh water--was run like a jail. Children were separated from parents to facilitate the work of civilizing them. The regimental daily schedule included Bible reading, hymn singing, and inspection of beds and dishes for cleanness and neatness. However, the jail diet caused malnutrition, which combined with illness to make the natives die. Few infants survived more than a few weeks. The government reduced expenditures in the hope that the native would die out. By 1869 only Truganini, one other woman, and one man remained alive."

PART 4

THE LAST TASMANIANS

With the steady decrease in the number of Aborigines, White people began to take a bizarre interest in the Blacks, whom Whites believed "to be a missing link between humans and apes." In 1859 Charles Darwin's book, On the Origin of Species, popularized the fantasy of biological (and therefore social) evolution, with Whites at the top of the evolutionary scale and Blacks at the bottom. The Aborigines were portrayed as a group of people "doomed to die out according to a natural law, like the dodo, and the dinosaur." This is during the same period in the United States that it was legally advocated that a Black man had no rights that a White man was bound to respect.

William Lanney, facetiously known as King Billy, was the last full-blood male Tasmanian. He was born in 1835 and grew up on Flinders Island. At the age of thirteen Lanney was removed with the remnant of his people to a concentration camp called Oyster Cove. Ultimately he became a sailor and some years he went whaling. As the last male Tasmanian, Lanney was regarded as a human relic. In January 1860 he was introduced to Prince Albert. He returned ill from a whaling voyage in February 1868, and on March 2, 1868 he died in his room at the Dog and Partridge public-house in Hobart, Tasmania.

Lanney, the subject of ridicule in life, became, in death, a desirable object. Even while he lay in the Colonial Hospital at least two persons determined to have his bones. They claimed to act in the interest of the Royal Society of Tasmania. On March 6, 1868, the day of the funeral, fifty or sixty residents interested in Lanney gathered at the hospital. Rumors were circulating that the body had been mutilated and, to satisfy the mourners, the coffin was opened. When those who wished to do so had seen the body, the coffin was closed and sealed. Meanwhile it was reported that, on the preceding night, a surgeon had entered the dead-house where Lanney lay, skinned the head, and removed the skull. Reportedly, the head of a patient who had died in the hospital on the same day was similarly skinned, and the skull was placed inside Lanney's scalp and the skin drawn over it. Members of the Royal Society were "greatly annoyed" at being thus forestalled and, as body-snatching was expected, it was decided that nothing should be left worth taking and Lanney's hands and feet were cut off. In keeping with the tradition no one was punished. William Lanney, the last Black man in Tasmania, was gone.

QUEEN TRUGANINI: THE LAST TASMANIAN

QUEEN TRUGANINI: THE LAST TASMANIAN

"Not, perhaps, before, has a race of men been utterly destroyed within seventy-five years. This is the story of a race which was so destroyed, that of the aborigines of Tasmania--destroyed not only by a different manner of life but by the ill-will of the usurpers of the race's land.... With no defences but cunning and the most primitive weapons, the natives were no match for the sophisticated individualists of knife and gun. By 1876 the last of them was dead. So perished a whole people." --Clive Turnbull

On May 7, 1876, Truganini, the last full-blood Black person in Tasmania, died at seventy-three years of age. Her mother had been stabbed to death by a European. Her sister was kidnapped by Europeans. Her intended husband was drowned by two Europeans in her presence, while his murderers raped her.

It might be accurately said that Truganini's numerous personal sufferings typify the tragedy of the Black people of Tasmania as a whole. She was the very last. "Don't let them cut me up," she begged the doctor as she lay dying. After her burial, Truganini's body was exhumed, and her skeleton, strung upon wires and placed upright in a box, became for many years the most popular exhibit in the Tasmanian Museum and remained on display until 1947. Finally, in 1976--the centenary years of Truganini's death--despite the museum's objections, her skeleton was cremated and her ashes scattered at sea.

CONCLUSION

The tragedy of the Black aborigines of Tasmania, however painful its recounting may be, is a story that must be told. What lessons do we learn from the destruction of the Tasmanians? Truganini's life and death, although extreme, effectively chronicle the association not only between White people and Black people in Tasmania, but, to a significant degree, around the world. Between 1803 and 1876 the Black aborigines of Tasmania were completely destroyed. During this period the Black people of Tasmania were debased, degraded and eventually exterminated. Indeed, given the long and well-documented history of carnage, cruelty, savagery, and the monstrous pain, suffering, and inhumanity Europeans have inflicted upon Black people in general, and the Black people of Tasmania in particular, one could argue that they themselves, the White settlers of Tasmania, far more than the ravenous beast portrayed in American cartoons, have been the real Tasmanian devil.

Copyright © 1998 Runoko Rashidi. All rights reserved.

Online Source: http://www.cwo.com/~lucumi/tasmania.html

The Destruction of the Aboriginal Tasmanians: A Bibliography

Compiled by Runoko Rashidi

"Tactics for hunting down Tasmanians included riding out on horseback to shoot them, setting out steel traps to catch them, and putting out poison flour where they might find and eat it. Sheperds cut off the penis of aboriginal men, to watch the men run a few yards before dying."

--Jared Diamond

Arthur, George. Van Diemen's Land: Copies of All Correspondence Between Lieutenant-Governor Arthur and His Majesty's Secretary of State for the Colonies. On the Subject of the Military Operations Lately Carried Against the Aboriginal Inhabitants of Van Diemen's Land. With an Historical Introduction by A.G.L. Shaw. Hobart: Tasmanian Historical Research Association, 1971.

Basedow, Herbert. "Relic of the Lost Tasmanian Race--Obituary Notice of Mary Seymour." Man 14 (1914): 161-62.

Bonwick, James. The Daily Life of the Tasmanians. London: Sampson Low & Son & Marston, 1870.

Branard, James. "The Last Living Aboriginal of Tasmania." The Mercury (Hobart), 10 Sep 1889.

Calder, J.E. Some Accounts of the Wars and Habits etc. of the Tribes of Tasmania. Hobart: n.p., 1875.

Cato, Nancy, and Vivienne Rae-Ellis. Queen Trucanini. London: Heinemann, 1976.

Chauncy, Nan. Hunted in Their Own Land. Introduction and Afterword by Barbara Bader. New York: Seabury Press, 1973.

Chenault, John. "Truganina." Poem in The Invisible Man Returns. Cincinnati: Ventana Media, 1992: 114-20.

Crowther, William Edward Lodewyk Hamilton. The Final Phase of the Extinct Tasmanian Race 1847-1876: Being an Epilogue to the Sixth Halford Oration. Launceston: Queen Victoria Museum, 1974.

Davies, David. The Last of the Tasmanians. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1974.

Diamond, Jared. "In Black and White." Natural History (Oct 1988): 8-14.

Diamond, Jared. "Ten Thousand Years of Solitude." Discover 14, No. 3 (Mar 1993): 48-57.

Johnson, C. Dr. Wooreddy's Prescription for Enduring the Ending of the World. n.p.: n.p., 1983.

Marchant, Leslie Ronald. A List of French Naval Records and Illustrations Relating to Australian and Tasmanian Aborigines, 1771 to 1828. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, 1969.

McMahon, Anne. "Tasmanian Aboriginal Women as Slaves." Tasmanian Historical Research Association, Papers and Proceedings 23, No. 2 (1976).

Miller, Robert S. Thomas Dove and the Tasmanian Aborigines. Melbourne: Spectrum, 1985.

Mollison, B.C. The Tasmanian Aborigines. Hobart: University of Tasmania, 1974.

Morris, James. "The Final Solution Down Under." 61-70.

Plomley, N.J.B. The Tasmanian Aborigines: A Short Account of Them and Some Aspects of Their Life. Launceston: Plomley, 1977.

Price, Pat Peatfield. The First Tasmanians. New York: Rigby, 1984.

Pybus, Cassandra. Community of Thieves. Melbourne: Heinemann, 1991.

Rae-Ellis, Vivienne. "Trucanini." Tasmanian Historical Research Association, Papers and Proceedings 23, No. 2 (1976).

Randriamahefa, Kerry. Aborigines and Tasmanian Schools. Research Study No. 44. Education Department of Tasmania.

Rashidi, Runoko. "Blacks as a Global Community." Dalit Voice 13, No. 19 (1994): 2-8.

Rashidi, Runoko. The Global African Community: The African Presence in Asia, Australia and the South Pacific. Washington, D.C.: Institute for Independent Education, 1994.

Rashidi, Runoko. "Dangerous Liaisons: A Historical Survey of Black-White Interaction." Image (Jan 1995): 14-18.

Rashidi, Runoko. "Black Death Down Under: Are White People Inherently Evil?" The Knowledge Broker (Aug 1995): 2-3.

Rashidi, Runoko. "The Black Presence in Tasmania: A Case of Genocide." The Challenger, 21, Feb 1996: 24.

Rashidi, Runoko. "Black War: The Destruction of the Tasmanian Aborigines." Rhythm of the Drum 2, No. 4 (1996): 18-22.

Rashidi, Runoko. "The Black Presence in Australia, Tasmania and the South Pacific." The Key 4, Issue 7 (Jul/Aug 1997): 2-4.

Rashidi, Runoko. "Tasmanian Devils--The Destruction of the Tasmanian Aborigines." Black History Magazine (1999): 57-63.

Reed, Bill. Truganinni. Richmond: Heinemann Educational Australia, 1977.

Robson, Lloyd. A History of Tasmania, Volume I: Van Diemen's Land from the Earliest Times to 1855. Oxford University Press, 1983.

Roth, Henry Ling. The Aborigines of Tasmania. 1899; rpt. Hobart: Fullers Bookshop, 1968.

Ryan, Lyndall. The Aboriginal Tasmanians. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press, 1981.

Sculthorpe, H. Tasmanian Aborigines: A Perspective for the 1980s. Hobart: Tasmanian Aboriginal Culture, 1980.

Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. The Story of Tasmanian Aboriginals. Hobart: Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, 1960.

Travers, Robert. The Tasmanians: The Story of a Doomed Race. Melbourne: Cassell, 1968.

Turnbull, Clive. Black War: The Extermination of the Tasmanian Aborigines. Introduction by Ian Hogbin. 1948; rpt. Melbourne: Lansdowne Press, 1965.

Turnbull, Clive. "Tasmania: The Ultimate Solution." Racism: The Australian Experience. A Study of Race Prejudice in Australia. Vol. 2, Black Versus White. Edited by Frank S. Stevens. New York: Taplinger, 1972: 228-34.

West, Ida. Pride Against Prejudice: Reminiscences of a Tasmanian Aborigine. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Arts, 1984.

Copyright © 1998 Runoko Rashidi. All rights reserved.

Online Source: http://www.cwo.com/~lucumi/tasmania-bib.html

Vivienne Rae Ellis

Late in the Spring of 1912, J. W. Beattie, a noted photographer with a penchant for recording historical anecdotes, paid a visit to the old people's home at St John's Church, New Town. In old age Fred Seager, the last person alive connected with the deaths of both Lanne and Trucanini, was eager to share his memories. As dispenser assistant at the public hospital, he told Beattie, he was the man who helped Dr Stokell cut up the body of Lanne to obtain the skeleton when the mutilated corpse was removed from the churchyard and hidden in one of the hospital storerooms in March 1869, It was, he admitted, a dirty job. Sergeant Townley, taken into Stokell's confidence and armed with several bottles, administered swigs of beer to the doctor and to Seager as the dissection proceeded throughout the night and their 'feelings prompted refreshment'.

According to Seager, Dr Crowther had taken Billy's head and, placing it in a seal's carcass, sent it to England. But the packing had been done so badly the stench was unbearable and the carcass was thrown overboard during the voyage. This report, popular at the time, was contradicted by Agnew, a former premier of Tasmania, who maintained in 1888 that Lanne's skull had been received safely in London by the museum of the Royal College of Surgeons although he made no comment on its packaging. A discussion on the teeth in the skull of William Lanne published in an Edinburgh journal nearly 40 years later lent support to his claim that the head reached England . The description of an 'articulated left hand', a 'partly dissected hand' and a pair of 'articulated right and left feet' in the collections of the Tasmanian Museum in 1964 indicates the final resting place of the extremities, at least, of poor Lanne's mutilated body, recalling the ditty Sir William Crowther often heard when he was a boy:

King Billy's dead. Crowther has his head

Stokell has his hands and feet.

My feet, my feet, my poor black feet

That used to be so gritty

They're not on board the Runnymeade

They're somewhere in this city.

After Trucanini died in 1876, Seager continued, her corpse was placed in a hospital outhouse and closely guarded to prevent any repetition of the Lanne affair. Old Bellamie of Port Arthur took good care that nothing should happen to the body while he was in charge. 'I slept on top of the coffin', he told Seager, 'all night!'

Some time later, according to Seager, Dr Agnew (then Honorary Secretary of the Royal Society) told Dr Coverdale, superintendent of the hospital, that 'they ought to have Trucanini's skeleton for the Museum' and asked him to arrange to have the body taken from the coffin and the skeleton removed. Coverdale was horrified--public feeling had run very high over the Lanne affair and he had no wish to be involved in a scandal like that of his unfortunate predecessor, Stokell. But the Royal Society was insistent. It faced determined competition in the acquisition of the skeleton just as it had at the time of Lanne's death. There was a disturbing story going the rounds a few days after Trucanini's burial that gave the learned members of the society good cause to fear the loss of her remains for ever.

According to rumour, a 'well-known medical man' (the evidence points to Dr W. L. Crowther) had recently obtained a prospecting lease on a tract of land which happened to include the cemetery of the Aborigines at Oyster Cove. Believing himself unobserved, the good doctor began to overhaul the graves 'where he no doubt expected to find ample compensation for his previous disappointment', only to find that someone had been there before him, so the story went. The Aboriginal skeletons had either been removed to a safer place or they were so imperfect as to have no commercial value. The press believed that when the station was abandoned precautions were taken to prevent skeletal remains 'becoming the spoil of private cupidity'.

In the face of this rumour poor Coverdale protested in vain. Under pressure from the influential Agnew he consulted Seager and obtained the services of a couple of convicts under sentence for murder to open Trucanini's grave and take out the coffin. The vault was full of water. When they opened the coffin, water poured out of it. The body was pulpy. 'The flesh was just like mutton-fat,' Seager told Beattie. 'You just sludged it off the bones as if it were fat!'

Seager believed the peculiar state of the body was due to immersion in water with a high mineral content. The flesh, minus the skeleton, was put back in the coffin, which was closed and returned secretly to the vault, care being taken to leave everything as before. Thomas Roblin, Curator of the Tasmanian Museum, knew all about the affair according to Beattie's personal knowledge. He took charge of the skeleton, packing the bones in an apple case with a tag label attached marked 'Trucanini's skeleton'.

Beattie gave no indication of the date of this secret and illegal exhumation of Trucanini's body but the Royal Society had been pressing the government for exhumation from the day following Trucanini's death. In July 1876 the Colonial Secretary replied to yet another request, saying that it would be 'premature to exhume the body at the present time' indicating quite clearly that it would be possible to do so at a later date. However, faced with the activities of the well known medico, the Royal Society decided delay was tantamount to defeat and took the matter into its own hands, just as it had done in the Lanne affair.

Agnew was a staunch supporter of the Royal Society and he was also a member of the ministry from August 1877 to December 1878. It was probably early in that period that he used his influence over Coverdale to insist on the illegal exhumation on behalf of the Royal Society and with the full (but unofficial) cooperation of the necessary authorities, an action that resulted in retention of the skeleton for the state while successfully thwarting the plans of others to obtain the remains.

Formal approval of the Governor-in-Council for the Society to exhume Trucanini's body was not received for two and a half years after her death and a considerable time after the event, officially closing the files and bringing to a legal conclusion the conspiracy conducted by influential citizens who had organised the whole affair. Permission for exhumation was given on the understanding that 'the skeleton shall not be exposed to public view but be decently deposited in a secure resting place where it may be accessible by special permission to scientific men for scientific purposes', according to the minutes of the Executive Council whose members were, presumably, unaware that the by then almost legendary skeleton of the Last Tasmanian had been rattling about in its apple case in an outhouse of the museum for months. The press innocently reported as a newsworthy item on 14 December 1878 that the body had just been exhumed, the bones denuded of flesh and the skeleton handed over to the Royal Society.

In the 1890s the then curator, Alexander Morton, was about to throw the battered old fruit box on to the rubbish heap when he 'just happened to catch the writing--very indistinct--of the tag label, and the skeleton was saved'. Or so Beattie believed. Early in the new century the skeleton was placed on public exhibition in a glass case at the entrance of the Aboriginal exhibition room in the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, where it remained until 1947.

Public interest in Trucanini intensified over the years, fanned by the occasional newspaper article recalling the tragic story of the extinct Tasmanians and discomforting the descendants of the race who had deposed them. The question of the future of her remains was raised and her last wishes regarding the disposal of her body became a topic of interest in letters to the editor in the Tasmanian press.

One of the first attempts to have Trucanini's bones removed from the museum and finally buried came from the church, a move intitiated by Archdeacon H. B. Atkinson, son of the Rev. A. D. Atkinson. The latter had been horrified to learn from a display of photographs, paintings and a cast of the face of Trucanini at the Melbourne Centennial Exhibition in 1888 that the morbid fear of his old Aboriginal friend at Oyster Cove concerning the ultimate fate of her body had been more than justified. The Archdeacon's appeal to the trustees of the Tasmanian Museum in 1950, based on his father's deep concern that Trucanini's wish should, even at this late hour, be granted was supported three years later by the Bishop of Tasmania who sought an 'honourable interment' for Trucanini's remains and the founding of an Aboriginal scholarship in her name.

The authorities canvassed the opinions of seven eminent scientists in the United Kingdom, New Zealand and Australia concerning disposal of Trucanini's skeleton, the only specimen of a female full-blood Tasmanian Aborigine available for study. To a man, the scientists expressed horror at the Bishop's proposal, describing it as a 'scientific crime of the worst order' that would receive worldwide condemnation and would not in any way atone for the original crimes committed against the living members of the Tasmanian race the previous century. Accepting their advice, the Premier notified the Bishop in 1954 that the government proposed to retain the skeleton, housing it in a specially designed section of the museum, which, however, was not completed until 1965.

Appeals were made throughout the 1950s and 1960s for the setting up of some permanent public memorial to Trucanini, but like similar proposals made by her friends at the time of her death they were ignored by the authorities. A schooner bearing the name Trucanini was wrecked back in 1842 and a hamlet in Victoria bore the name of 'Truganina' but nothing in the land of her birth marked her life or her death.

On 8 May 1965, partly as a result of increasing public pressure, partly as a security measure, and timed to coincide with the 89th anniversary of her death, Trucanini's remains were placed in a vault in the Tasmanian Museum, and in September 1967 the first monument to the Tasmanian Aborigines was erected. Although dedicated to the memory of all Aborigines, it honoured in particular Mangana, chief of the Bruny Island tribe, and his daughters, Moorina and 'Truganini', in the shape of a cairn on the Truganini Lookout at Bruny Island. Reports of the unveiling ceremony sparked off once again demands in the press that Trucanini's last request for a decent burial should be honoured. The opposing view favoured retention of the skeleton for scientific study, an opinion held by the majority of interested scientists and endorsed by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies in 1970.

In the early 1970s the black rights movement sprang into the headlines of newspapers throughout Australia and quickly became recognised as an organisation capable of applying powerful political pressure, Aboriginal activists seized on the matter of the final disposal of Trucanini's remains as a political issue. The centenary of her death in 1976 provided an ideal focal point for their campaign. Possession of Trucanini's skeleton became the prize in a bitterly fought contest.

Government authorities and scientific institutions involved in the affair found themselves in a quandary and began shifting ground: on the one hand they were sympathetic to the demands of the Aboriginal people that the remains should receive a dignified burial; on the other, as men of science and custodians of the collections belonging as much to future generations as to the present and the past, they recognised the potential value of extended study of the skeletal material, particularly in view of rapidly advancing investigative techniques, and were understandably reluctant to see the bones destroyed and lost forever. The black activists argued that museums were not the usual repositories for the skeletons of the famous, and denounced the action of the Tasmanian Museum in retaining the remains as an indication of the measure of contempt felt by the whites for the blacks, and they stepped up their demands for removal of the skeleton from the museum's vault. The Trustees, claiming they did not have the power to release the bones or the authority to arrange for their cremation or burial, appealed in June 1974 to the Tasmanian government to take custody of the remains and so relieve the trustees of a responsibility that had become, almost overnight, a major political and racial issue.

By the authority of a special Act of Parliament dated 24 January 1975 the remains of Trucanini were vested in, and became the property of, the Crown and the immediate responsibility of the Chief Secretary, the Hon D. A. Lowe, MLC, who set up a committee consisting of himself, the director of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery and the secretary of the Aboriginal Information Service in Tasmania to organise the disposal of the controversial remains, After conferring with the Aboriginal lnformation Service, Lowe announced that Trucanini's remains were to be buried early in 1976. His decision was challenged by several organisations including the National Aboriginal Congress which claimed on moral grounds the right of Congress to dispose of the remains of Trucanini, now recognised as an Aboriginal identity of national importance. Lowe rejected the claim. He believed local Aborigines had the right to represent the national Aboriginal viewpoint on the matter.

The Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies also expressed dissatisfaction at Lowe's plans. Following the Tasmanian Museum's request for an opinion on the matter in 1974 the Institute reversed its earlier recommendation of 1970 to preserve the skeleton and recommended disposal of the remains immediately in accordance with Trucanini's wishes, or with those of her descendants. The Institute was aware that very little research had been carried out on Trucanini's bones in the 98 years they had been available for scientific study.

At the annual general meeting of the Aboriginal Information Service in 1975 a motion was passed to the effect that the skeleton should be cremated and the ashes scattered over D'Entrecasteaux Channel. Lowe, however, felt committed to return the bones to the ground, and the government acquired land at Mt Nelson for that purpose.

For some months the blacks and the government were at loggerheads, unable to reach agreement on the method of disposal of the skeleton. The advantages of cremation versus burial were argued at length. Lowe finally proposed a compromise. He referred the matter to Cabinet which, in the middle of March 1976, agreed to cremation and the scattering of ashes in D'Entrecasteaux Channel, rescinding an earlier decision to cremate and bury the ashes at the Mt Nelson site. Far from settling the matters this decision only served to fan the flames of controversy, Reports of government decisions and counter-decisions were prominently reported in the press and public feeling ran high. The opposition now entered the fray, pointing out that on the grounds of legislation passed in 1974 Trucanini's bones were required to be 'decently interred'. While agreeing with Cabinet's final decision, the opposition stressed the necessity for further legislation to legalise the scattering of the ashes.

At this point doubts were raised about the claim that Trucanini was the last Tasmanian. The battle raged.

Legal action against the government was threatened by a group of Aborigines from Warrnambool in Victoria, who claimed to be descended from Trucanini. Undeterred, the Tasmanian Upper House authorised passage of the Bill in April 1976 to allow cremation of the skeleton while the Warrnambool Aborigines considered seeking an injunction to prevent this on the grounds that they believed Trucanini wished to be buried, not burned. Their spokesman, Len Clarke, admitted there was no 'whiteman's proof' in the form of documentary evidence to support his claim that there were many descendants of Trucanini living in Victoria, but he stated firmly that there was no doubt of it. The link, he told the press, began with the escape of one of Trucanini's daughters from Tasmania to the mainland, a statement discounted by the evidence discussed earlier indicating Trucanini had no children and recognised no descendants at the time of her death.

Disturbed by the political implications of the dispute now raging not only between blacks and whites but also between opposing Aboriginal factions over possession of Trucanini's skeleton, Lowe requested a representative of the Tasmanian blacks to meet the Warrnambool people in an effort to sort out their differences and settle the matter once and for all. After a five-hour discussion the Aboriginal leaders reached agreement. The Victorian Aborigines accepted the point made by the Tasmanians that if Trucanini's bones were buried there was no guarantee that they would not, once again, be stolen from the ground. They agreed to cremation of the remains.

On 30 April 1976 the long-awaited and much discussed decision was implemented. Trucanini's remains were cremated at the Cornelian Bay crematorium, where the oration was delivered by Rosalind Langford, former Secretary of the Aboriginal Information Service in Tasmania.

The following morning, 1 May 1976, just seven days short of the centenary of her death, Trucanini's ashes were placed in a specially made pinewood container and carried on board the Hobart Marine Board launch Egeria by senior police officers. In the presence of Acting-Premier Lowe and 21 representatives of Aboriginal communities (among them 90-year old Mary Clarke and Len Clarke of Warrnambool, who claimed to be descendants of Trucanini) the ashes were borne down river. An hour and a half later, in long-delayed compliance with the impassioned plea Trucanini had made 107 years earlier as she knelt before the Rev. Atkinson in the little rowing boat rocking on the deep waters at the Shepherds, Roy Nicholls, State Secretary of the Aboriginal Information Service in Tasmania, scattered her ashes in D'Entrecasteaux Channel close to the place of her birth at Adventure Bay. There was no ceremony, the only sound the whispering of the wind, the whirring of television cameras, and the murmurs of mourners and newsmen accompanying Egeria in a flotilla of small boats.

A few days later the Tasmanian Numismatic Society issued a medallion commemorating the centenary of Trucanini's death, a memorial plaque was unveiled at the Town House in Macquarie Street, the site of her former residence in Hobart, and on 8 May a woodland park at Mount Nelson was officially opened and named in Trucanini's honour.

The week marking the centenary of Trucanini's first burial, also witnessed her second. The cremation of her skeleton and dedication of monuments to her memory ended years of bitter fighting, political haggling and genuine concern, and appeared to bring to a close the Trucanini controversy.

From Trucanini: Queen or Traitor? Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, 1981.

Return to Wendy Rose