Sandburg On Race

Comments on Sandburg's attitudes toward black Americans and racism in America, focusing on Sandburg's coverage of the 1919 race riots in Chicago for the Chicago Daily News. Includes an excerpt from Aldon Nielsen's Reading Race and brief comment on "Nigger," "Elizabeth Umpstead," and "Man, the Man-Hunter." Selections from three chapters of Sandburg's The Chicago Race Riots, 1919: the author's introduction, "Trades for Colored Women," and "About Lynchings."

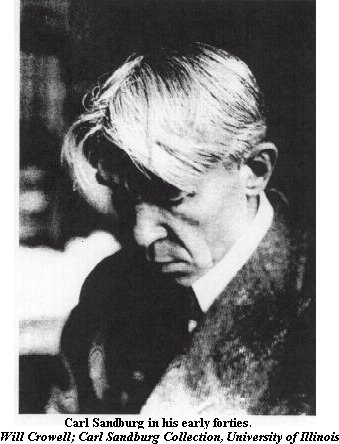

Carl

Sandburg's Swedish immigrant upbringing in Galesburg, Illinois, offered him little by way

of direct experience with black Americans. His working-class roots and his association

with socialist politics, likewise, were no guarantee of sympathy with blacks. In the first

decades of the century, white laborers were often antagonistic toward blacks whom they

believed would threaten their unions, their wages, even their jobs. The Socialist Party of

America had a spotty record in race relations, and Sandburg's work as an organizer for the

Socialist Democratic Party in Wisconsin gave him plenty of contact with German immigrants

but relatively little with African Americans.

Carl

Sandburg's Swedish immigrant upbringing in Galesburg, Illinois, offered him little by way

of direct experience with black Americans. His working-class roots and his association

with socialist politics, likewise, were no guarantee of sympathy with blacks. In the first

decades of the century, white laborers were often antagonistic toward blacks whom they

believed would threaten their unions, their wages, even their jobs. The Socialist Party of

America had a spotty record in race relations, and Sandburg's work as an organizer for the

Socialist Democratic Party in Wisconsin gave him plenty of contact with German immigrants

but relatively little with African Americans.

Sandburg's work in the 1910s as a Chicago reporter, however, brought him into contact with one of the fastest growing centers of black population in the United States. Between 1914 and 1919, Sandburg himself reported, Chicago's black population had grown by 70,000, most of them recent migrants from the South. During the first decade of Sandburg's residence in Chicago he also became personally acquainted with the leaders of the Industrial Workers of the World, headquartered there since 1914. In the I.W.W., which he grew to admire, Sandburg discovered not only the most radical union of the day but also the most egalitarian one in racial politics.

Sandburg's fairness and sympathy toward blacks--though not untouched by bias--are in evidence in the sequence of reports he filed in the summer of 1919 with the Chicago Daily News, which were begun prior to the race riots of July and took on a larger, prescient significance afterwards. Late in the year, the fifteen articles in the series were collected and put into print as a book by Harcourt and Company. The first chapter of The Chicago Race Riots, 1919, written retrospectively to furnish an overview of the collection, reports briefly on the riot itself:

THE so-called race riots in Chicago during the last week of July, 1919, started on a Sunday at a bathing beach. A colored boy swam across an imaginary segregation line. White boys threw rocks at him and knocked him off a raft. He was drowned. Colored people rushed to a policeman and asked for the arrest of the boys throwing stones. The policeman refused. As the dead body of the drowned boy was being handled, more rocks were thrown, on both sides. The policeman held on to his refusal to make arrests. Fighting then began that spread to all the borders of the Black Belt. The score at the end of three days was recorded as twenty negroes dead, fourteen white men dead, and a number of negro houses burned.

Sandburg might have added details indicating further the extent to which the race riot was founded on institutional racism and white violence against blacks. Some such details he might well not have been aware of: For example, initially, the victim's companions found a black police officer and fingered a suspect, but the white officer mentioned by Sandburg intervened to prevent an arrest. Other incriminating details Sandburg either surely knew of but chose to suppress, or could have discovered: The riots lasted not for three but for fourteen days, and while Sandburg has the number of whites killed nearly right (15 was the exact number), there were 30, not 20, blacks killed, and 7 of them were killed not by rioters but by police. Blacks were arrested at twice the rate of whites, in spite of the fact that blacks suffered greater casualties--342, as opposed to 195 whites, were reported injured (Tuttle 5-10, 64).

Why, in his introduction to The Chicago Race Riots, did Sandburg downplay the extent of violence in the riots? (It is noteworthy that in a later letter to his brother-in-law also discussing the riots he used inflated casualty figures.) His three assertions about their historical significance, spelled out at the end of the prefatory chapter 1, make clear enough both his understanding of the social circumstances underlying the riot and his indignation toward racism. Also clear, however, are his wishes to protect the reputation of a current city administration that he sees as progressive and to see the riots as a moment of labor solidarity across ethnic and racial divisions, and these political objectives might have prevailed over his providing a more complete account of the riots. Sandburg's "factors that give the Chicago flare-up historical import" were as follows:

1. The Black Belt population of 50,000 in Chicago was more than doubled during the war. No new houses or tenements were built. Under pressure of war industry the district, already notoriously overcrowded and swarming with slums, was compelled to have and hold in its human dwelling apparatus more than twice as many people as it held before the war.

2. The Black Belt of Chicago is probably the strongest effective unit of political power, good or bad, in America. It connects directly with a city administration in its refusal to draw the color line, and a mayor whose opponents failed to defeat him with the covert circulation of the epithet of "nigger lover." To such a community the black doughboys came back from France and the cantonment camps. Also it is known that hundreds--it may be thousands--have located in Chicago in the hope of permanent jobs and homes in preference to returning south of Mason and Dixon's line, where neither a world war for democracy, nor the Croix de Guerre, nor three gold chevrons, nor any number of wound stripes, assures them of the right to vote or to have their votes counted or to participate responsibly in the elective determinations of the American republic.

3. Thousands of white men and thousands of colored men stood together during the riots, and through the public statements of white and colored officials of the Stockyards Labor Council asked the public to witness that they were shaking hands as "brothers" and could not be counted on for any share in the mob shouts and ravages. This was the first time in any similar crisis in an American community that a large body of mixed nationalities and races--Poles, Negroes, Lithuanians, Italians, Irishmen, Germans, Slovaks, Russians, Mexicans, Yankees, Englishmen, Scotchmen--proclaimed that they were organized and opposed to violence between white union men and colored union men.

Aldon Nielsen writes critically of Sandburg's poetry and journalism from the period of the race riots, which reveal Sandburg to be "operating within the poetic tradition of white speech" (34). The evidence Nielsen culls from Sandburg's correspondence with his brother-in-law, the photographer Edward Steichen, is compromising indeed:

The extent to which Sandburg, in his early years, subscribed to the structure of the racial beliefs we have been examining may be gauged from two letters he addressed to his brother-in-law, Edward Steichen, shortly after the violence had subsided. In the first of the letters the poet tells the photographer that he has "spent ten days in the black belt and [is] starting a series of articles . . . on why Abasynnians, Bushmen and Zulus are here" (Sandburg, Letters 166). He of course did nothing of the sort and would have been hard pressed to locate a bushman in Chicago in any event. What was really bothering Sandburg was the, to him, unjustifiable increase in black population in his city. Like Lindsay after the Springfield riots, Sandburg seemed to think the blacks brought all this on themselves by failing to stay where they belonged. The second letter discussing the series of articles Sandburg set out to write is dated six months later and exhibits stark racism. In it, Sandburg reports: "The last figures I heard as to the race riot death toll was 35 negro dead and 20 white men. . . . The stories of many niggers being killed and hidden are bosh. It's a damn hard job to get rid of one corpse in a big city" (Letters 175). (Nielsen 35)

Yet in spite of Sandburg's white racist "discursive blinders" that he "was never able wholly to free himself of," Nielsen also writes of "rare occasions in Sandburg's poetry when the nonwhite breaks through the veil of the poet's internalized systems of speech. The times that Afro-America is heard most clearly in his poems are the times when Sandburg stops speaking of or for them and simply listens to the voice of the nonwhite" (37, 36).

Always, however, this is a complex negotiation, in which white stereotypes of blacks constantly threaten to encroach upon genuine representation of black voices--and just what might count as "genuine representation" is always in question. Nielsen describes Sandburg's "Nigger" as "a monologue which sounds as if spoken by the dead metaphor itself," but argues that the poem "takes a turn at the end which indicates that Sandburg may have begun to examine more closely the racial idioms he sopke so naively . . . . It is as if the stereotype suddenly stood up on its own and gestured threateningly toward its maker" (36, 37). The same struggle is evident in Sandburg's "Elizabeth Umpstead," which by particularizing the voice of the black, female speaker may avoid the broad racial stereotypes of "Nigger" but risks reinforcing other stereotypes specific to African-American women. It may be that, as Cary Nelson writes, "Poems indicting the culture's violent racism were . . . more manageable than poems evoking the specificities of black culture" (Repression and Recovery 118). From this angle, Sandburg's "Man, the Man-Hunter," which exposes the brutality of white racism from within by quoting the voice of a lynch mob, may prove a less problematical poem than either "Nigger" or "Elizabeth Umpstead." But white representation of black voices needs to be faced as an issue in any case, for if rapprochement between black and white Americans is to progress, then the approach toward racial understanding must be considered through the perspectives of white as well as black writers.

Sandburg's shortcomings as a commentator on--let alone as a speaker for--black America are evident throughout his writing. The following excerpts from The Chicago Race Riots, which provide at the same time background for Sandburg's race poetry and important commentaries in themselves, do reveal Sandburg to be both a sympathetic pleader for the cause of black civil rights and a reporter willing to let black voices speak for themselves. The degree to which Sandburg's sympathy turns to paternalism, and the degree to which his quotations represent an appropriation and misrepresentation of black speech, remain open and important questions.

[Chapter 8]

TRADES FOR COLORED WOMEN

A COLORED woman entered the office of a north side establishment where artificial flowers are manufactured.

"I have a daughter 17 years old," she said to the proprietor.

"All places filled now," he answered.

"I don't ask a job for her," came the mother's reply. "I want her to learn how to do the work like the white girls do. She'll work for nothing. We don't ask wages, just so she can learn."

So it was arranged for the girl to go to work. Soon she was skilled and drawing wages with the highest in the shop. Other colored girls came in. And now the entire group of fifteen girls that worked in this north side shop have been transferred to a new factory on the south side, near their homes. At the same time a number of colored girls have gone into home work in making artificial flowers.

Such are the casual, hit-or-miss incidents by which the way was opened for colored working people to enter one industry on the same terms as the white wage earners. . . .

Of the 170 firms in Chicago that employed colored women for the the first time during the war, 42, or 24 per cent, were hotels or restaurants, which hired them as kitchen help or bus girls. Twenty-one, or 12 per cent, were hotels or apartment houses which hired them as chambermaids. Nineteen laundries, 12 garment-factories, seven stores, and eight firms, hiring laborers and janitresses, make up the rest of the 170. The packing industry, of course, leads all others in employment of both colored men and women as workers. Occupations that engaged still others during the war were picture framers, capsule makers, candy wrappers, tobacco strippers, noodle makers, nut shellers, furniture sandpaperers, corset repairers, paper box makers, ice cream cone strippers, poultry dressers and bucket makers. . . .

Here and there, slowly and by degrees, the line of color discrimination breaks.

* * * *

The comment of a trained industrial observer on the colored woman as a machine operator is as follows. . . .

"Replacement for colored women [of women workers for men], however, does not mean advancement in the same sense as for white women. Because the white woman has been in industry for a long time, and is more familiar with industrial practices, she is less willing to accept bad working conditions. The colored woman, on the other hand, is handicapped by industrial ignorance and drifts into conditions of work rejected by white workers. Colored women are found on processes white women refuse to perform. They replace boys and men at cleaning window shades, dyeing furs, and in one factory they were found bending constantly and lifting clumsy 160 pound bales of material. . . .

"At the time of the greatest labor shortage in the history of this country, colored women were the last to be employed. They did the most menial and by far the most underpaid work. They were the marginal workers all through the war, and yet during those perilous times, the colored woman made just as genuine a contribution to the cause of democracy as her white sister in the munitions factory or her brother in the trench. She released the white women for more skilled work and she replaced colored men who went into service."

* * * *

A creed of cleanliness was issued in thousands of copies by the Chicago Urban league during the big influx of colored people from the south. It recognized that the women, always the woman is finally responsible for the looks and upkeep of a household, and made its appeal in the following language:

"For me! I am an American citizen. I am proud of our boys 'over there,' who have contributed soldier service. I desire to render citizen service. I realize that our soldiers have learned new habits of self-respect and cleanliness. I desire to bring about a new order of living in this community. I will attend to the neatness of my personal appearance on the street or when sitting in the front doorway. I will refrain from wearing dustcaps, bungalow aprons, house clothing and bedroom shoes when out of doors. I will arrange my toilet within doors and not on the front porch. I will insist upon the use of rear entrances for coal dealers and hucksters. I will refrain from loud talking and objectionable deportment on street cars and in public places. I will do my best to prevent defacement of property, either by children or adults."

Two photographs went with this creed. One showed an unclean, messy front porth, the other a clean, well kept front porch. Such is the propaganda of order and decency carried on earnestly and ceaselessly by clubs, churches and leagues of colored people, struggling to bring along the backward ones of a people whose heritage is 200 years of slavery and fifty years of industrial boycott.

As an aside from the factual and humdrum of the foregoing, here is a letter, vivid with roads and bypaths of spiritual life, written by a colored woman to her sister in Mississippi. It is a frank confession of one sister soul to another of what life has brought, and as a document is worth more than stacks of statistics.

"My Dear Sister:--I was agreeably surprised to hear from you and to hear from home. I am well and thankful to say I am doing well. The weather and everything else was a surprise to me when I came. I got here in time to attend one of the greaterst revivals in the history of my life. Over 500 people joined the church. We had a Holy Ghost shower. You know I like to have run wild. It was snowing some nights and if you didn't hurry you could not get standing room. . . .

"I am quite busy. I work for a packing company in the sausage department. We get $1.50 a day and we pack so many sausages we don't have much time to play, but it is a matter of a dollar with me and I feel that God made the path and I am walking therein.

"Tell your husband work is plentiful here and he won't have to loaf if he wants to work. I know unless old man A------ changed it was awful with his soul. Well, I guess I have said about enough. I will be delighted to look into your face once more in life. Pray for me, for I am heaven bound. I have made too many rounds to slip now. I know you will pray for me, for prayer is the life of any sensible man or woman. Good-by."

[Chapter 11]

ABOUT LYNCHINGS

"Eleven persons joined our church the other Sunday and they were all from Vicksburg, Miss., where there had been a lynching a few weeks before," said Dr. L. K. Williams, colored pastor of the largest protestant church in North America, in an address to the Baptist Minsters' council of Chicago.

Tuskeegee institute records of lynchings the first six months of this year show the following numbers in the states named: Alabama, 3; Arkansas, 4; Florida, 2; Georgia, 3; Louisiana, 4; Mississippi, 7; Missouri, 1; North Carolina, 2; South Carolina, 1; Texas, 1. The total, 28, is seven less than in the corresponding period of 1918 and fourteen more than in the corresponding period of 1917.

Not only is Chicago a receiving station and port of refuge for colored people who are anxious to be free from the jurisdiction of lynch law, but there has been built here a publicity or propaganda machine that directs its appeals or carries on an agitation that every week reaches hundreds of thousands of people of the colored race in the southern states. . . .

The Defender is the dean of the weekly newspaper group, and it is said to reach more than 100,000 subscribers in southern states. A Carnegie foundation investigator records his belief that the Defender, more than any other one agency, was the cause of the "northern fever" and the big exodus from the south in the last three years. It advocates race pride and race militancy and exhausted the vocabulary of denunciation on lynching, disfranchisement, and all forms of race discrimination.

At some postoffices in the south it was difficult to have copies of the Defender delivered to subscribers. A colored man caught with a copy in his possession was suspected of "northern fever" and other so-called disloyalties. Thousands of letters poured into the Defender office asking about conditions in the north.

This situation has a curious political reflex. A rumor arose. It traveled to Chicago and Washington. It said that sinister forces were operating to prevent negroes in the north and particularly in Chicago from returning to their former homes in the south. Down south the rumor traveled and was published to the effect that thousands of colored men and women were walking the streets of Chicago, hungry and without shoes, begging for transportation to Dixie, the home of the cotton blossoms that they were longing to see again.

Lieut. W. L. Owen of the military intelligence service at Washington was sent to Chicago to investigate. He went to Dr. George C. Hall, a leader in several colored organizations, and asked, "What is this undercurrent that is keeping the negroes in the north?" Dr. Hall answered, "There isn't any undercurrent. Everything is in the open in this case. The trouble started when the Declaration of Independence was written. It says that every man has a right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. So long as the colored people get more of those three things in the north than in the south they are going to keep coming, and they are going to stay."

Dr. Hall told the intelligence officer that the situation reminded him of the reply of the colored band leader to Liza Johnson, who asked what was the occasion of the brass band's parading the streets one evening. The reply was, "Lordy, Liza, don't you know we don't need no occasion?"

The declaration of Dr. Williams to the Baptist Ministers' association that eleven new members came from Vicksburg has a direct connection with a lynching story which is being widely circulated by the publicity or propaganda batteries of South State street, reaching at least 1,000,000 of the illiterate colored people of the south. The story, for ingenious cruelty and with relation to the kind of barbarism that is worse for the practitioners than the victims, equals anything recited in recent European war atrocities or anything in the Spanish inquisition of more ancient days.

In Vicksburg, in the third week in June, the story goes, a colored man accused of an assault on a white woman was placed in a hole that came to his shoulders. Earth was tamped around his neck, only his head being left above ground. A steel cage five feet square then was put over the head of the victim and a bulldog was put inside the cage. Around the dog's head was tied a paper bag filled with red pepper to inflame his nostrils and eyes. The dog immediately lunged at the victim's head. Further details are too gruesome to print.

Whatever may be the truth of this amazing story, it is published in newspapers of the colored people and is attested as a fact by Sectretary A. Clement McNeal of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, whose local office is at 3333 South State street.

The last named organization, the most militant in activities against lynching, will hold its annual convention next year for the first time in a southern city. It will go to Atlanta on invitation of the mayor of that city and on request of Gov. Dorsey of Georgia. This is one of several indications that the southern states are actively considering steps to be taken to retain their negro population and to lessen the violence which threatens to become a habit in a number of communities.

Return to Carl Sandburg