On "Dark Symphony"

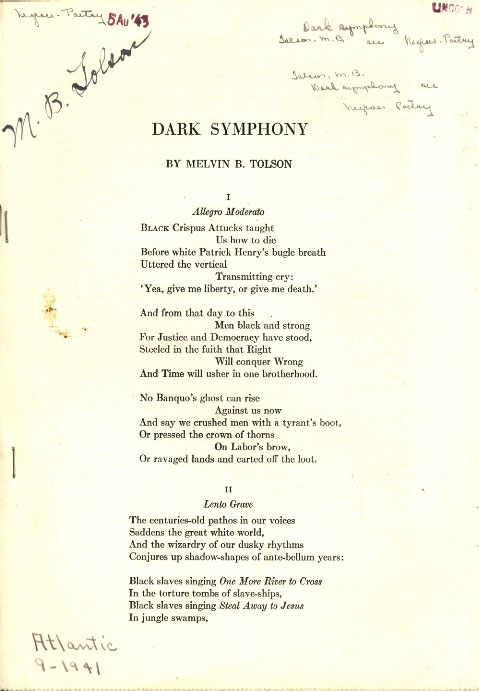

An Autographed Manuscript Page from "Dark Symphony"

Michael Bérubé (1992)

The only notable exception to Tolson’s acclaim by African-American critics in the 1940s is a notice by Robert A. Davis, whose critique of "Dark Symphony" in the Chicago Sunday Bee of 21 September 1941 apparently affected Tolson greatly. Davis offered strong support for the poem overall (and a schoolmasterly injunction for its further dissemination): "The poem is definitely worth reading. It will be talked about for a long time to come and you should have comments based on your own impressions to contribute to the discussions ‘Dark Symphony’ will provoke." But alone among the poem’s critics, Davis considered the work lamentably uneven. Citing Tolson’s "use of well worn allusions … coupled with the obvious fault of redundance," he suggested that some sections were "far short of what the author is capable of and intends." Davis particularly contrasted the poem’s "perfect" first six lines with its next six, protesting that "it is almost sacrilege to follow such magnificent lines with others as flat and Pollyannaish" as these:

And from that day to this

Men black and strong

For Justice and Democracy have stood,

Steeled in the faith that Right

Will conquer Wrong,

And Time will usher in one brotherhood.

Davis’s objection is well taken, and apparently Tolson thought so too, for he revised the stanza before it was published in Rendezvous with America. Some anthologists have reprinted only the earlier version, however, so let us look at both versions side by side. Here is the revision:

Waifs of the auction block,

Men black and strong

The juggernauts of despotism withstood,

Loin-girt with faith that worms

Equate the wrong

And dust is purged to create brotherhood.

Because Tolson has so long and so often been accused of revising Libretto at Allen Tate’s behest, it may be helpful to note that this revision (together with a few minor adjustments to the third stanza) appears to be the only section of the Tolson oeuvre whose different versions were motivated by published professional criticism. Though Allen Tate, like Robert Davis, had deigned to point out Tolson’s weaknesses, it appears that Tolson was no more moved by Tate’s reservations than he was by Poetry’s initial rejection of Libretto in 1948 – a rejection upon which he signified when he wrote to James Decker, at the Decker Press, that "maybe [Poetry’s editors] think the propaganda sticks through the seams of the verse."

From Michael Bérubé, Marginal Forces / Cultural Centers: Tolson, Pynchon, and the Politics of Canon (Ithaca: Cornell U P, 1992), 168-170.

Robert M. Farnsworth (1984)

Tolson made some changes in the text of "Dark Symphony" between its publication in Atlantic Monthly in September 1941 and its publication in Rendezvous with America [in 1944]. The most important changes are in the opening stanza, but another, minor change is significant thematically. In stanza 4, line 4, as it appears in the book, his is underlined: "The New Negro Speaks in his America." The effect of much of what Tolson has said about America in the two opening sections of [Rendezvous with America], and now in "Dark Symphony," is to stake out a claim by definition. America is a nation of the people, not a nation of the Big Boys. It is a nation of a people who have learned to respect the rights and dignity of other people, not a nation of exploiters, racists, or demagogues. The latter are the true un-Americans. Black people share in the authentic American heritage as richly as do any other people:

Black Crispus Attucks taught

Us how to die

Before white Patrick Henry’s bugle breath

Uttered the vertical

Transmitting cry:

"Yea, give me liberty or give me death."

The songs of black slaves conjure up "shadow-shapes of ante-bellum years," "One More River to Cross," "Steal Away to Jesus," "The Crucifixion," "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot," and "Go Down, Moses" are provided just enough of a dramatic context to make clear that these songs carried sustaining messages that only the slaves understood. The wrongs that have been suffered must not be forgotten. The New Negro proclaims the accomplishments of his ancestors and boldly shares in the most important cultural activities of today. He is free of the exploitation, profiteering, and fascist subversion that call the Americanness of other Americans into question:

Thus,

Out of abysses of Illiteracy,

Through labyrinths of Lies,

Across waste lands of Disease …

We advance!Out of dead-ends of Poverty,

Through wildernesses of

Superstition,

Across barricades of Jim Crowism

…We advance!With the Peoples of the World …

We advance!

The democratic promise of America is expanded into a global dream for mankind, and within that dream black America will find challenge, recognition, and support. The rendezvous with America is a rendezvous with self-realization for all the peoples of the world who have been excluded from the full democratic dream by poverty, class, or race.

From Robert M. Farnsworth, Melvin B. Tolson, 1898-1966: Plain Talk and Poetic Prophecy (Columbia, U Missouri P, 1984) 81-82.

Rita Dove (1999)

… "Dark Symphony" is a lyrical tour de force, a sweeping review of black American history in musical vocabulary. The poem is divided into six sections, and each section is assigned a musical signature. The upbeat optimism of Allegro Moderato describes the black contribution to the Revolutionary War effort. This early idealism is made drear by the escalating horrors of slavery, exquisitely rendered in Lento Grave ("slow and stately") in the second section, horrors that are then made spiritually bearable only by the nourishment of gospel, what W. E. B. Du Bois calls the Sorrow Songs. The iambic trimeter of Andante Sostenuto underscores the abeyance of those years when the emancipation promise of "forty acres and a mule" had soured into the institution of sharecropping:

They tell us to forget

The Bill of Rights is burned.

Three hundred years we slaved,

We slave and suffer yet.

Though flesh and bone rebel,

They tell us to forget!

The dawning of the Harlem Renaissance heralds the birth of Alain Locke’s famous "New Negro"; the fourth section, aptly marked Tempo Primo, both points toward the future and harkens dramatically back to the ungrounded optimism of the Revolutionary War period. Sure enough, the next section (Larghetto) rebukes white America for its failures: each stanza begins with the refrain "None in the land can say / To us black men Today," followed by examples of the violence and deceit plaguing the Depression years. The final section regales in march time (Tempo di Marcia) the determination of the New Black American to advance "Out of the dead ends of Poverty" and "Across barricades of Jim Crowism" to a better world.

From Rita Dove, "Introduction," "Harlem Gallery" and Other Poems of Melvin B. Tolson, ed. Raymond Nelson (Charlottesville: U Virginia P, 1999), xiv-xv.

Return to Melvin Tolson