About Marian Anderson and Her Lincoln Memorial Concert

D. Antoinette Handy

Anderson, Marian (27 Feb. 1897-8 Apr. 1993), contralto, was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the daughter of John Berkeley Anderson, a refrigerator room employee at the Reading Terminal Market, an ice and coal dealer, and a barber, and Anne (also seen as "Annie" and "Anna," maiden name unknown), a former schoolteacher. John Anderson's various jobs provided only a meager income, and after his death, before Marian was a teenager, her mother's income as a laundress and laborer at Wannamaker Department Store was even less. Yet, as Anderson later recalled, neither she nor her two younger sisters thought of themselves as poor. When Marian was about eight her father purchased a piano from his brother; she proceeded to teach herself how to play it and became good enough to accompany herself. Also as a youngster, having seen a violin in a pawn shop window, she became determined to purchase it and earned the requisite $4 by scrubbing her neighbors' steps. She attempted to teach herself the violin as well but discovered that she had little aptitude for the instrument.

Anderson joined the children's choir of Union Baptist Church at age six. Noticing her beautiful voice and her ability to sing all the parts, the choir director selected her to sing a duet for Sunday school and later at the regular morning service; this was her first public appearance. Later she joined the senior choir and her high school chorus, where occasionally she was given a solo.

While she was still in high school, Anderson attempted to enroll at a local music school but was rejected with the curt statement, "We don't take Colored." She applied and was accepted to the Yale University School of Music, but a lack of finances prevented her from enrolling. Although she was not the product of a conservatory, Anderson was vocally prepared by Mary Saunders Patterson, Agnes Reifsnyder, Giuseppe Boghetti, and Frank La Forge. Over the years she was coached by Michael Raucheisen and Raimond von zur Mühlen, and she also worked briefly (in London) with Amanda Aldridge, daughter of the famous black Shakespearean actor Ira F. Aldridge. Boghetti, however, had the greatest pedagogical influence.

Anderson's accompanists (with whom she enjoyed excellent relationships) were African Americans Marie Holland and William "Billy" King (who for a period doubled as her agent), Finnish pianist Kosti Vehanen, and German pianist Franz Rupp. Between 1932 and 1935 she was represented by the Arthur Judson Agency; from 1935 through the remainder of her professional life, the great impresario Sol Hurok.

One of the happiest days of Anderson's life was when she called Wannamaker to notify her mother's supervisor that Anne Anderson would not be returning to work. On another very happy occasion, in the late 1920s, she was able to assist in purchasing a little house for her mother in Philadelphia. Her sister Alyce shared the house; her other sister, Ethel, lived next door with her son James DePreist, who became a distinguished conductor.

For many, including critics, an accurate description of Anderson's singing voice presented challenges. Because it was nontraditional, many simply resorted to the narrowly descriptive "Negroid sound," Others, however, tried to be more precise. Rosalyn Story, for example, has described Anderson's voice as "earthy darkness at the bottom ... clarinet-like purity in the middle, and ... piercing vibrancy at the top. Her range was expansive--from a full-bodied D in the bass clef to a brilliant high C" (p. 38). Kosti Vehanen, recalling the first time he heard Anderson's "mysterious" voice, wrote, "It was as though the room had begun to vibrate, as though the sound came from under the earth.... The sound I heard swelled to majestic power, the flower opened its petals to full brilliance; and I was enthralled by one of nature's rare wonders" (p. 22). Reacting to his first encounter with the voice Sol Hurok wrote, "Chills danced up my spine ... I was shaken to my very shoes" (Story, p. 47).

In 1921 Anderson, who was already a well-known singer at church-related events, won the National Association of Negro Musicians (NANM) competition. Believing that she was ready for greater public exposure she made her Town Hall (New York City) debut in 1924. Disappointed by the poor attendance and by her own performance, she considered giving up her aspirations for a professional career. The following year, however, she outcompeted 300 other singers to win the National Music League competition, earning a solo appearance with the New York Philharmonic at Lewisohn Stadium.

In 1926, with financial assistance from the Julius Rosenwald Fund, Anderson departed for Europe for further musical study. After returning to the United States, she gave her first Carnegie Hall concert in 1930. That same year she gave her first European concert, in Berlin, and toured Scandinavia. In 1931 alone she gave twenty-six concerts in fifteen states. Between 1933 and 1935 she toured Europe; one of her appearances was at the Mozarteum in Salzburg, where the renowned conductor Arturo Toscanini uttered the memorable line, "Yours is a voice such as one hears once in a hundred years" (My Lord, What a Morning, p. 158). Another exciting experience took place in the home of noted composer Jean Sibelius in Finland. After hearing Anderson sing, he uttered, "My roof is too low for you," then canceled the previously ordered coffee and requested champagne. Sibelius also honored Anderson by dedicating his composition Solitude to her.

Anderson's second Town Hall concert, arranged by Hurok and performed on 30 December 1935, was a huge success. A one-month tour of the Soviet Union was planned for the following year but ended up lasting for three months. She was a box office sensation as well in Europe, Africa, and South America.

Anderson's seventy U.S. concerts in 1938 continues as the longest and most-extensive tour in concert history for a singer. Between November 1939 and June 1940 she appeared in more than seventy cities, giving ninety-two concerts. Her native Philadelphia presented her with the Bok Award in 1941, accompanied by $10,000. She used the funds to establish the Marian Anderson Award, which sponsors "young talented men and women in pursuit of their musical and educational goals."

During 1943, a very special year, Anderson made her eighth transcontinental tour and married architect Orpheus H. Fisher of Wilmington, Delaware. The marriage was childless. In 1944 she appeared at the Hollywood Bowl, where she broke a ten-year attendance record. In 1946, 600 editors in the United States and Canada, polled by Musical America, named Anderson radio's foremost woman singer for the sixth consecutive year. Anderson completed a South American tour in 1951 and made her television debut on the "Ed Sullivan Show" the following year. Her first tour of Japan was completed in 1953, the same year that she also toured the Caribbean, Central America, Israel, Morocco, Tunisia, France, and Spain.

Anderson sang the national anthem at the inauguration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1957, and between 14 September and 2 December of that year she traveled 39,000 miles in Asia, performing twenty-four concerts under the auspices of the American National Theater and Academy and the U.S. State Department. Accompanying Anderson was journalist Edward R. Murrow, who filmed the trip for his "See It Now" television series. The program, which aired on 30 December, was released by RCA Records under the title The Lady from Philadelphia. In 1958 Anderson served as a member of the U.S. delegation to the General Assembly of the United Nations. Three years later she sang the national anthem at the inauguration of President John R Kennedy, appeared in the new State Department auditorium, and gave another concert tour of Europe. Her first tour of Australia was a highlight of 1962.

In early 1964 Hurok announced Marian Anderson's Farewell Tour, beginning at Constitution Hall on 24 October 1964 and ending on Easter Sunday 1965 at Carnegie Hall. The momentousness of the event was reflected in Hurok's publicity: "In any century only a handful of extraordinary men and women are known to countless millions around the globe as great artists and great persons.... In our time there is Marian Anderson." After the tour she made several appearances as narrator of Aaron Copland's A Lincoln Portrait, often with her nephew James DePreist at the podium.

Although in her own lifetime Anderson was described as one of the world's greatest living contraltos, her career was nonetheless hindered by the limitations placed on it because of racial prejudice. Two events in particular that illustrate the pervasiveness of white exclusiveness and African-American exclusion--even when it came to someone of Anderson's renown--serve as historical markers not only of her vocal contributions but also of the magnificence of her bearing, which in both instances turned two potential negatives into resounding positives.

In 1938, following her numerous international and national successes, Hurok believed it was time for Anderson to appear in the nation's capital, at a major hall. She had previously appeared in Washington, D.C., at churches, schools, civic organization meetings, and at Howard University, but she had not appeared at the district's premiere auditorium, Constitution Hall. At that time, when negotiations began for a Marian Anderson concert to be given in 1939 at the Daughters of the American Revolution-owned hall, a clause appeared in all contracts that restricted the hall to "a concert by white artists only, and for no other purpose." Thus in February 1939 the American who had represented her country with honor across the globe was denied the right to sing at Constitution Hall simply because she was not white.

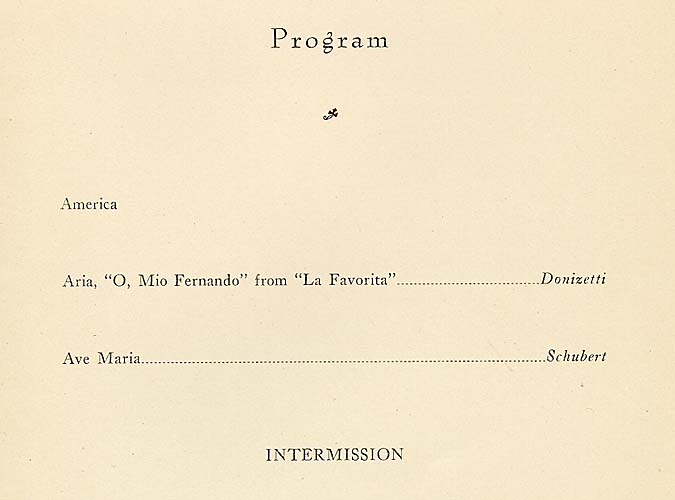

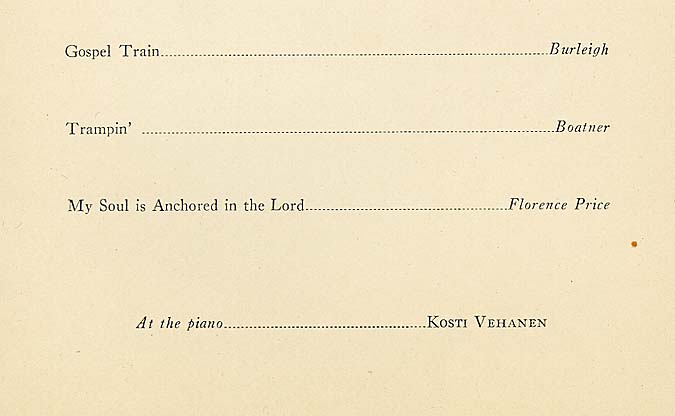

A great furor ensued, and thanks to the efforts of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, the great contralto appeared the following Easter Sunday (9 Apr. 1939) on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial before an appreciative audience of 75,000. She began the concert by singing "America" and then proceeded to sing an Italian aria, Schubert's Ave Maria, and three Negro spirituals, "Gospel Train," "Trampin,"' and "My Soul Is Anchored in the Lord." Notably, she also sang "Nobody Knows the Trouble I've Seen." Commemorating the 1939 Lincoln Memorial concert is a mural at the Interior Department; it was formally presented in 1943, the year that Anderson made her first appearance in Constitution Hall, by invitation of the Daughters of the American Revolution and benefiting United China Relief.

The second history-making event came on 7 January 1955, when Anderson made her debut at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York, becoming the first black American to appear there. Opera had always interested Anderson, who tells the story in her autobiography of a visit with the noted African-American baritone Harry T. Burleigh, during which she was introduced to and sang for an Italian gentleman. When she climbed the scale to high C, the man said to Burleigh, "Why sure she can do Aida," a traditionally black role. On her first trip to England, Anderson had visited a teacher who suggested that she study with her, guaranteeing that she would have her singing Aida within six months. "But I was not interested in singing Aida," Anderson wrote. "I knew perfectly well that I was a contralto, not a soprano. Why Aida?"

Anderson's pending debut at the Met was announced by the international press in October 1954. As educator-composer Wallace Cheatham later noted, the occasion called for the most excellent pioneer, "an artist with impeccable international credentials, someone highly respected and admired by all segments of the music community" (p. 6). At the time there was only one such individual, Marian Anderson. About Anderson's debut, as Ulrica in Verdi's Un Ballo in Maschera (The masked ball), Time magazine (17 Jan. 1955) reported that there were eight curtain calls. "She acted with the dignity and reserve that she has always presented to the public.... Her unique voice--black velvet that can be at once soft and dramatic, menacing and mourning--stirring the heart as always."

In addition to her other awards and honors, Anderson was a recipient of the Spingarn Medal (NAACP), the Handel Medallion (New York City), the Page One Award (Philadelphia Newspaper Guild), and the Brotherhood Award (National Conference of Christians and Jews), and she was awarded twenty-four honorary doctorates. She was cited by the governments of France, Finland, Japan, Liberia, Haiti, Sweden, and the Philippines. She was a member of the National Council on the Arts, was a recipient of the National Medal of Arts, and in 1978 was among the first five performers to receive the Kennedy Center Honors.

Several tributes were held in the last years of Anderson's life. In February 1977 the musical world turned out to recognize Anderson's seventy-fifth (actually her eightieth) birthday at Carnegie Hall. On 13 August 1989 a gala celebration concert took place in Danbury, Connecticut, to benefit the Marian Anderson Award. The concert featured recitalist and Metropolitan Opera star Jessye Norman, violinist Isaac Stern, and maestro Julius Rudel conducting the Ives Symphony Orchestra. Because Anderson's residence, "Marianna," was just two miles from the Charles Ives Center, where the concert was held, the 92-year-old grand "lady from Philadelphia" was in attendance. Educational television station WETA prepared a one-hour documentary, "Marian Anderson," which aired nationally on PBS on 8 May 1991. She died two years later in Portland, Oregon, where she had recently moved to live with her nephew, her only living relative.

Many actions were taken posthumously to keep Anderson's memory alive and to memorialize her many accomplishments. The 750-seat theater in the Aaron Davis Arts Complex at City College of New York was named in her honor on 3 February 1994. The University of Pennsylvania, as the recipient of her papers and memorabilia, created the Marian Anderson Music Study Center at the Van Pelt-Dietrich Library. Of course, the greatest legacy are the ones who came after. As concert and opera soprano Leontyne Price, one of the many beneficiaries of Anderson's efforts, said after her death, "Her example of professionalism, uncompromising standards, overcoming obstacles, persistence, resiliency and undaunted spirit inspired me to believe that I could achieve goals that otherwise would have been unthought of " (New York Times, 9 April 1993).

Anderson's papers and memorabilia are housed at the Van Pelt-Dietrich Library at the University of Pennsylvania. Shortly before her death a birth certificate was located, verifying her year of birth as 1897 rather than the 1902, 1903, or 190? listed in various biographical sources. Her autobiography is My Lord, What a Morning (1956); several of her life philosophies are shared in Brian Lanker, I Dream a World (1989). Very complete entries are included in the Biographical Dictionary of Afro-American and African Musicians, ed. Eileen Southern (1982); Black Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia, ed. Darlene Clark Hines et al. (1993); Donald Bogle, Brown Sugar: Eighty Years of America's Black Female Superstars (1980); Rosalyn Story, And So I Sing (1990); and Southern, The Music of Black Americans: A History, 2d ed. (1983). Of tremendous value is the biography by her early accompanist Kosti Vehanen, Marian Anderson: A Portrait (1941; repr. 1970). As a valuable reference, see Janet Sims, Marian Anderson: An Annotated Bibliography and Discography (1981). Wallace Cheatham's comments about Anderson's debut at the Metropolitan Opera House are included in his "Black Male Singers at the Metropolitan Opera," Black Perspective in Music 16, no. 1 (Spring 1988): 3-19. An excellent, front-page obituary is in the New York Times, 9 Apr. 1993. See also the appreciation by Joseph McLellan, "TheVoice That Tumbled Walls," Washington Post, 9 Apr. 1993.

From American National Biography. Ed. John A. Garraty and Mark C. Carnes. New York: Oxford UP, 1999. Copyright © 1999 by the American Council of Learned Societies.

A Photo-Essay on Marian Anderson

The following images are all excerpted from the much larger online exhibit "Marian Anderson: A Life in Song," curated by Nancy M. Shawcross at the Annenberg Rare Book & Manuscript Library at the University of Pennsylvania. Click here to visit the exhibit.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The Program for the Lincoln Memorial Concert,

April 9, 1939.

|

|

|

Return to Genevieve Taggard