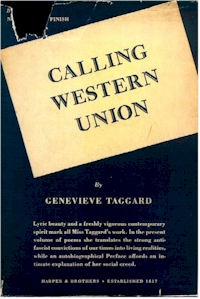

On Calling Western Union

Rebecca Pitts

Here in my opinion,

Genevieve Taggard has taken the longest and most important step in her evolution as a

major poet. Let us say it very clearly: there is some great poetry in Calling Western

Union. The poet has succeeded in integrating the implications of a great them with the

imaginative realization of her own intimate experiences. It is the tragic theme of our

era: the conflict in human lives between the ruin and dissolution of the old order, and

the vision we cherish of the new. The psychological form of the conflict is the struggle

between individualism and the collective ideal; and to present this conflict the poet must

himself cast off old romantic illusions about "poetic grandeur"--or he must

perish like the poet in one of Taggard’s most successful poems:

Here in my opinion,

Genevieve Taggard has taken the longest and most important step in her evolution as a

major poet. Let us say it very clearly: there is some great poetry in Calling Western

Union. The poet has succeeded in integrating the implications of a great them with the

imaginative realization of her own intimate experiences. It is the tragic theme of our

era: the conflict in human lives between the ruin and dissolution of the old order, and

the vision we cherish of the new. The psychological form of the conflict is the struggle

between individualism and the collective ideal; and to present this conflict the poet must

himself cast off old romantic illusions about "poetic grandeur"--or he must

perish like the poet in one of Taggard’s most successful poems:

Then he died

snap like any business man

worry over strain

burst a blood vessel . . .

Scoop his grave with the jolly steam shovel.

One scoop will do . . .

And for the grave-going poet

Take from the darkened room the ghost-haunted

glass--

Give him this mark for his grave. Set here for his

grave-stone

His perfect companion the mirror.

But this whole theme of social and psychological conflict is a high and difficult one; and only a major poet can present it without imposing upon half-realized material the pattern of half-absorbed slogans.

That is why I say that Taggard has taken an important step. She has always had a high degree of imaginative integrity; one always felt that she reacted to experience with the whole woman. Her shrewd and sensitive imagery, her intimate psychological acuteness, the vein of thought and witty reasonableness that runs through her verse; these qualities revealed a mind, a heart, and a keen pair of eyes, all responding to life freshly and sincerely, and integrating the response into new imaginative perceptions. In the past, however, it might have been said that her range was too personal. In this new book there is a change; intellectual and emotional awareness of a larger world illuminates even the slighter poems.

In thirty-eight poems and five prose messages the poet presents a moving record of our time. Take the Preface: "Hawaii, Washington, Vermont." It is simple, colloquial prose, but very vivid; and it makes you see, not only the Taggard family back from Hawaii and stranded in an ugly western wheat town, but the long trek of thousands going West and conquering the prairies, but not for the good life. When the first struggle was over, they left desolation in the plains; a community of empty souls, their only values a hatred of foreigners and a resentment against the "stuck up." Thus, in terms of the poet’s own life we see the sorry end of the pioneer impulse: "individualism, the credo of their fathers, had starved them."

With the implications of that story as a frame for the picture, the poems present many aspects of the conflict of today. Interspersed are the four "Note Books," short passages in prose illuminating the poetry with another kind of wisdom. The poems range from little satirical portraits of decay, through simple and moving records of poverty and sorrow, and militant chants of the masses, brave and unbeaten, to songs of the future which somehow clothe with emotional reality our dreams of collective living. Throughout is the undercurrent of emotions explicit in:

Deepest of all essential to the song

In common good, grave dogma of the throng.

In such a poem as "On Planting a Lilac in Vermont" there is a homely simplicity that is in the spirit of Frost:

The doorstep that it’s by is farmer style.

But it is no New England rugged individualist who says:

Planting for future people with sure hands

Is pleasure of the purest....

The significant thing about these poems, however, is that Genevieve Taggard has wrestled with her own past, and with the burden of today’s perceptions of cities and wasted country sides, of poverty and twisted lives; and that she has realized these experiences in genuinely imaginative terms in the light of a new set of social and revolutionary values. This is what I call important revolutionary poetry.

from Rebecca Pitts,"Tough, Reasonable, Witty." New Masses (October 1936) 22.

Return to Genevieve Taggard